It seems strange, if you look at Irish or Welsh mythology, that there doesn’t seem to be any thunder-god like Thor. However, among the Celtic peoples of continental Europe, we find the god Taranis, whose name means “thunder” and who sometimes wields a thunderbolt.1

Three altars dedicated to him come from France (Thauron, Orgon and Tours), two from Germany (Bockingen and Godramstei), one from Croatia (Scardona) , two from Amiens in Belgium, and one from Britian (Chester). (There is also an incised bone fragment from Tesero di Sottopendonda in Italy, saying simply “Taranis”, although this may be someone’s name.)

The Chester altar is interesting because it syncretizes Taranis (spelled Tanarus) with Jupiter Optimus Maximus, or Best and Greatest, the Roman god at his most imposing and official. As we shall seem Jupiter and Taranis were often paired.

Jupiter and Taranis

Another altar, from Alt Often in Hungary, is also dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus Taranucus. The image above, from Le Chatelet, Gourzon, Haute-Marne, France is probably of Taranis, and blends his attribute of the wheel and Jupiter’s thunderbolt.

While Jupiter (and Zeus) both have names meaning essentially “God”, Taranis, like Thor, Donar and the Baltic Perkunas, means simply “Thunder”. His name comes from a Celtic root *taran- meaning “thunder, thunderstorm” and is related to the Welsh, Breton and Cornish taran, thunder. His name goes right back to Indo-European roots.

Although Jupiter was the king of the gods, with a correspondingly important cult, Taranis doesn’t seem to have had anything like the same status in Celtic religion. Julius Caesar doesn’t mention a thunderer in his description of Gaulish religion, and you would think that if there was a local equivalent of Jupiter, he would have said so. Mercury seems to have been a much more important god in Gaul, based on the number of altars and art, and the richness of those altars compared to Taranis’. (MacKillop: 402)

For a long time, scholars of the Roman empire tended to think that the Romans came along and interpreted the local deities to suit themselves. Certainly, an inscription to Jupiter Taranis suggests Roman influence. But over the last 20 years scholars have turned this idea around, studying the interpretatio celtica, or how the locals interpreted Roman deities to match up with theirs. Perhaps Jupiter was the nearest thing to a thunder-god the Romans had.

Another image of Jupiter shows how the influence could go both ways. While the statuette above shows the god Celtic-style, with trousers and bare chest, another statue from Vaison shows the god in toga, with Jupiter’s eagle on one side, and Taranis’ wheel held against his other leg.

Other altars to Jupiter in France and Germany show him with the eagle and wheel, usually one on each side, like one from Alzey which shows Jupiter (or Taranis?) seated and wearing a cloak, with the wheel on his right and an eagle holding a ring on the left. Another from Baignon shows Jupiter holding a sceptre, with the eagle on the right and a five-spoked wheel to his left. The Willingham Sceptre from England combines the two gods’ attributes by having the eagle sit on the wheel. (Ross: 347-8) Also, two British altars dedicated to Jupiter were decorated with the wheel, suggesting that it was Taranis they meant. (Ross: 475)

Taranis and the Wicker Man

Taranis, along with the Gaulish gods Esus and Teutates, has a reputation for desiring human sacrifice A verse by the Roman poet Lucan helped to boost this image:

And those who pacify with blood accursed

Savage Teutates, Hesus’ horrid shrines,

And Taranis’ altars, cruel as were those

Loved by Diana, goddess of the north2;

Lucan (Pharsalia, Book 1)

The ninth-century Berne Scholia, which is an annotated version of the Pharsalia, expands on this, saying that Teutates (Mercury) and preferred drowned victims, Esus (Mars) preferred hanging while Taranis (Jupiter) liked burning. Since both Julius Caesar and Strabo described the Gauls burning victims in a “wicker man” it has been assumed that Taranis was the god they being sacrificed to.

However, both their accounts can be traced back the Roman writer Posidonius, whose work has been mostly lost to time. While he did travel widely throughout the Roman empire, we don’t know if he actually ever saw anything like a wicker man, which sounds pretty implausible. (How would you get the people into it, and how would you stop them kicking their way to freedom? Anyone who’s ever owned wicker furniture knows how flimsy it is.)

Interestingly, Lactanius, considered a father of the church, also described the three gods as bloodthirsty, although he saw Taranis as a form of Dis Pater, god of riches and the underworld. According to him, sacrifices to Taranis took place in a grove, where people were burned in a wooden vat as an offering. (Which seems more likely.)

Other commentaries said that Taranis was originally offered human heads. (Duval 1989: 277) Whether the Gauls ever did offer elaborate human sacrifices to these three gods, many Roman writers and others using them as sources believed that they did.

Wheel-God

One symbol often associated with the cult of Taranis is the wheel. Images of him holding the wheel are common enough that some have identified the bearded god on the Gundestrup Cauldron with him. Votive offerings of little wheels are common throughout Celtic areas in the Bronze Age, and have been found in a shrine in Alesia, in the Seine, and buried in tombs.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taranis#/media/File:Rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg

" data-medium-file="https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=300&h=176" data-large-file="https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=625" class="aligncenter wp-image-17681 size-medium" src="https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=300&h=176" alt="" width="300" height="176" srcset="https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=300&h=176 300w, https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=600&h=352 600w, https://earthandstarryheaven.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/rouelle_votive_wheels.jpg?w=150&h=88 150w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" style="margin: 0.857143rem auto; padding: 0px; border: 0px; font-size: 18.2px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; max-width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 3px; box-shadow: rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.2) 0px 1px 4px; clear: both;">You might wonder why a wheel, since they’re usually identified with the sun. Taranis could have been a sun-god as well, or a sky-god generally, although neither fits well with his name. Miranda Green argues that Taranis and the Wheel-God are separate beings, since the wheel must be a solar symbol.

Others have argued that the two are the same, citing the fact that both are conflated with Jupiter, and that Taranis occasionally holds a wheel as well. (The statuette above shows him with a wheel and a further supply of S-shaped objects, which could be extra lightning bolts.) Green also states that the wheel and thunderbolt often occur together in Gaulish religious art, which suggests that the two have something in common. (Green 1997: 210)

Germanic lore said that the groaning of thunder was caused by Thor’s wagon wheels and lightning was sparks they struck as they went. (If you imagine an old-fashioned wooden wagon with wooden wheels, you can see the logic of it.) Grimm (166) offers many examples, from both Germanic folklore and others’, of this idea.

Lightning also took the form of a wheel: the Indian epic the Mahabharata has a wheel that spits lightning bolts when it turns, and a fiery discus with a pole through the centre, probably a form of the Sudarshana Chakra. In Slavic folklore “thunder-marks“, rather like the hex marks of the Pennsylvania Dutch, include a circular one symbolizing ball lightning.

Or, to come at this from another angle, perhaps by Roman times the Bronze Age symbol of the wheel had become a sort of general symbol of good fortune and blessing, such that it would not seem incongruous besides a thunderbolt. Thor’s hammer was both a symbol of thunder and blessing, so perhaps the Gauls wished to indicate something similar by putting the two together.

Our picture of Taranis is contradictory: the wheel and thunderbolt could both indicate a benevolent deity, and his assimilation to Jupiter suggests a majestic god, but the written sources say that he was a “master of war”, who could be assimilated to Dis Pater as well as his celestial brother, and desired human sacrifice. This last may be just Roman propaganda, and perhaps we would be better off thinking of him as a benevolent warrior armed with a thunderbolt, like Jupiter smiting the Titans, whom Virgil describes as “cast down by a thunderbolt”.

1. The hammer-god Sucellos may be another, along with Mars Loucetius (Lighting).

2. His reference to “Scythian Diana” referred to the cult of Artemis at Taurica. In the Iliad, Iphigenia is sacrificed there so the Greek navy can have fair winds.

References

Duval, Pierre-Marie 1993: “Taranis,” trans. Gerald Honingsblum, in American, African and Old European Mythologies, compiled by Yves Bonnefoy, University of Chicago Press.

Green, Miranda 1979: “The Worship of the Romano-Celtic Wheel-God in Britain seen in Relation to Gaulish Evidence,” Laotumus (Apr.-May 1979) 38/2: 345-67.

Green, Miranda 1997: Dictonary of Celtic Myth and Legend, Thames and Hudson.

Grimm, Jacob 2014: Tetuonic Mythology vol. 1, Forgotten Books. (reprint, available on Scribd)

MacKillop, James 2004: An Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, OUP.

Links:

Wikipedia article

Balkancelts (lots of good pictures)

Britannica entry

To Jupiter Best and Greatest – Deo Mercurio (more on equestrian Jupiters)

Pagan Files blog on Celtic thunder-gods

Taranis et Thor

The Berne Scholia text (in Latin)

Comicvine‘s take on Taranus

The image at the top can be found here.

The eight-spoked wheel

The wheel represents authority and dominion, the way things are, and Buddhist teaching. The eight spokes of the wheel refers to the eightfold path, which is elaborated in the precepts. The wheel is dominion, the way things are, and the buddhist teaching.

The first archaeological evidence, mainly of ornamental stone carvings, comes from the time of the Emperor Asoka (273 – 232 BCE), who converted to Buddhism and made it a popular religion in India and beyond.

In Japan, the Nyoirin Kannon is most often depicted as six-armed and holding up a wheel, rinpou 輪宝 with one arm and proffering a “wish-fulfilling jewel” *nyoi houju 如意宝珠 with another arm. These images were largely carved between the Nara Period through Heian Periods.

In very early Buddhist art, to represent Buddha the symbols used were mainly the Eight Spoked Wheel along with the Bodhi Tree, the Buddha’s Footprints, an Empty Throne, a Begging Bowl and a Lion.

The Eight-Spoked Dharma Wheel or ‘Dharmachakra’ (Sanskrit) symbolises the Buddha’s turning the Wheel of Truth or Law (dharma = truth/law, chakra = wheel).

The wheel (on the left and right) refers to the story that shortly after the Buddha achieved enlightenment, Brahma came down from heaven and requested the Buddha to teach by offering him a Dharmachakra. The Buddha is known as the Wheel-Turner: he who sets a new cycle of teachings in motion and in consequence changes the course of destiny.

The Dharmachakra has eight spokes, symbolising the Eight-fold Noble Path. The 3 swirling segments in centre represent the Buddha, Dharma (the teachings) and Sangha (the spiritual community). The wheel can also be divided into three parts, each representing an aspect of Buddhist practice; the hub (discipline), the spokes (wisdom), and the rim (concentration).

Reference Source:

Ixion

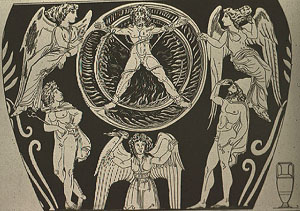

Ixion was the first man to shed kindred blood, by tricking his father-in-law to walk over (and fall into!) a camouflaged pit of burning coals. Zeus purified him after this crime, but Ixion repayed this favor by trying to rape Hera. In punishment for this second crime, Zeus had Ixion bound to a constantly revolving wheel. Different traditions place this wheel either in Hades or in the sky (see below).

This engraving from 1790 A.D. shows Ixion among the sufferers in Hades. To the left of Ixion you may recognize Atlas holding the world on his shoulders. The figure on the right is probably Tantalus trying to drink from a waterfall.

The red-figure vase below shows Ixion bound to a fiery wheel. According to Ovid (Metamorphoses Book 10), Ixion was punished in the underworld. The Greek poet, Pindar, however, gives a different account (P.2.21-24):

“They say that Ixion, through the gods’ commands revolving upon the winged wheel, cries out to men that they should always hasten to pay back their benefactor with kind deeds”