Rough Notes:

The World Tree & Its Function in Myth

In exploring the concepts of the World Tree, it is interesting to recall that the mythologist Joseph Campbell, after a lifetime of study devoted to the myths and legends of cultures spanning the planet, identified four functions of myth that were common to all its manifestations. The second of these was “to present an image of the cosmos… that will maintain your sense of mystical awe and explain everything that you come into contact with in the universe around you” (Campbell, 6–10). Naturally, different cultures have employed different symbols and frameworks to accomplish this, but for over a century now, the widespread centrality of the tree in this key role has been a subject of analysis and debate.

Some evolutionary psychologists suggest that the ubiquity of the “world tree” is rooted in the simian origins of humanity and the centrality of trees to the lives of our evolutionary ancestors (Karlson, 157). Regardless of its source, however, the concept is so widespread as to have been treated extensively by Carl Jung as an archetype of the collective unconscious (see, in particular, Man and His Symbols).

World Tree from Scandinavia to Siberia—The Hanging Tree & the Shaman’s Ladder

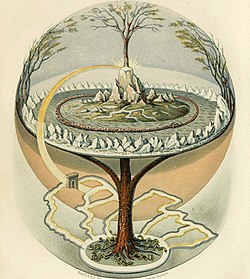

World Tree “Yggdrasil”

(Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, 1882)

Probably the most famous “world tree” is Yggdrassil—the great ash whose roots and branches, in Scandinavian lore, connected the nine realms of gods, men, giants, and elves. Its three roots extended to three sacred wells, at the last of which the chief god, Oðin, gave his eye to gain wisdom. Oðin’s connection with the tree was exceedingly intimate. One of the more commonly proposed etymologies for the name Yggdrassil is “Oðin’s horse” which, in the Norse poetic tradition of kenning (using a standard picturesque or metaphorical phrase as a standin for a common word) translates as “gallows.” And indeed, the most important Norse myth directly concerning the tree is that in which Oðin hanged himself by his spear from a branch as ‘a sacrifice of himself to himself,’ (as it says in the thirteenth century poem Hávamál) in order to learn the secret of the runes. This act, central to Norse conceptions of Oðin as a master of magick and hidden wisdom, had a real-life parallel in a tree planted at the great temple in Uppsala, Sweden, which stood green in both summer and winter, and hung its boughs over a pool where human sacrifices were drowned—an account similar to descriptions of human sacrifice in other sources, which depict those offered to Oðin as being hanged from trees, in likely imitation of him. In both cases, the tree likely represents the return to the sacred center and the realization of unity with the cosmic order.

A fascinating twist on this theme is given through another important Oðinic story (found in the thirteenth century poem Völuspá), in which Oðin, shortly after having fashioned the world with his brothers Vili and Ve from the body of the primordial giant Ymir, is walking along a beach with the gods Lóðurr and Hoenir and comes across two trees. The gods take pity on these, because they have no sense and no destiny, and so each of the three contribute a gift to them, forming them into the first man and woman—Ask (Ash) and Embla (Elm). Ash, of course, is the same species as Yggdrassil itself, and it has been proposed by some scholars that when, in the Norse account of the Ragnarök (or end of the world) two humans survive the cataclysm by hiding in a wood, that the reference is, in fact, to the recreation of humanity out of the stock of the world tree (Simek, 115). In this way, the Norse cosmology draws an implicit connection between the axis mundi and man as microcosm—a connection implicit in the world tree across many cultures.

World Tree (J. Augustus Knapp, 1928)

Illustration from The Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall

In fact, some scholars suggest that Norse understandings of the world tree as the connecting link between the various spiritual realms in an exoteric sense was influenced by their more ancient neighbors, such as the Finns, the Saami, and the wildly diverse tribes of Siberia (Davidson, 69). In those cultures, shamans undertaking trances or vision journeys often used the image of a tree to describe their inner ability to move up and down the levels of spiritual reality and between human and spirit realms. Decorative and symbolic motifs found across Siberia connect the underworld, this world, and the heavens through the image of a tree, which is often also a symbol of the Earth itself conceived as a mother goddess who gives the shaman both his drum and his power of astral travel. The appearance of world tree designs in the symbolism of the Crowns of Silla—an ancient Korean kingdom that flourished between the first century BC and the tenth century AD—is sometimes used to argue for a connection between Siberian cultures and the cultures of the Korean peninsula (Kidder, 105).

At the far opposite end of this mythic zone, conceptions startlingly similar to those of the Siberian tribes are found in Hungarian folklore. The Magyar tribes that migrated into the Carpathian basin from Siberia’s far western edge during the tenth century brought with them tales of Világfa (literally “world tree”), which they also called égig érő fa (“the sky-high tree”), életfa (“the tree of life”), or tetejetlen fa (“the tree without a top”). Magyar shamans, called táltosok, could climb the world tree to roam the seven or nine layers of the sky (depending on the version of the story). Later folktales tend to feature a downward descent as well.

Similar accounts can be found in Turkic culture, where the tree is called Ağaç Ana, Mongolian stories, which name it Modun, Finnish tales that make it an unnamed oak (as many Slavic tales do also), and Chinese annals, which term it Kien- or Jian-Mu. In many of these, as in the Hungarian version, the tree grows atop a world mountain, which forms an integral part of the axis mundi along with the tree. In some regions, as in Greece, the mountain has effectively displaced the tree. In ancient Greek lore, Mt. Olympus often fulfills the realm-joining functions of the tree, although medieval folk stories from Greece restore the tree as the pillar that holds up the world (adding a crowd of goblins, the kallikantzaroi, who are perpetually sawing at its base).

Other Indo-European cultures surrounding northern Eurasia, particularly the Balts (Vélius 1989), keep the world tree as central. Across this whole region, spanning from the Baltic Sea to the Sea of Japan, a number of details are surprisingly constant (Usačiovaitė, 67), particularly that the tree’s top is inhabited by one or more eagles, and that one or more serpents are entwined around its base (like the dragon, Niðhöggr, who gnaws at the roots of Yggdrassil).

World Tree in India—The Treehouse of the Gods

While many of the traditions surrounding world trees in Norse, Baltic, and other European cultures may be the result of cultural diffusion from Siberian, FinnoUgric, and other peoples, much undoubtedly comes from a common Indo-European source, as similarities to Vedic traditions make clear. In India, the role of the world tree is fulfilled not by an ash, but the peepal (or “sacred fig”), which is marked out as holy in some of the earliest lines of the Rig Veda (I.164.20). The Sanskrit name ashvattha, also used as a name of Vishnu and of Shiva, was held by Adi Shankara to be derived from the words shva (“tomorrow”) and stha (that which remains), referring to the tree’s eternally enduring nature (Dalal, 44). It was believed to inhibit lies, and older Vedic and Upanishadic literature refers to it as a “tree of knowledge” (Haberman, 70). Perhaps for this reason, Vedic tradition held that the fire god Agni resided in the ashvattha tree, and used its deadwood to kindle the triple sacrificial fires. Triple association was then extended to the tree itself as Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva grew in the classical period to be preeminent in the Hindu pantheon—the roots represented Brahma, the Creator of all things, the trunk represented Shiva, the Destroyer, and the branches stood for Vishnu, the Sustainer (72) (modern Hindus, however, frequently reverse the last two associations [77]).

With the development of more formalized, monistic theologies, the tree gradually became associated with whichever deity a given school regarded as supreme (as when Krishna in the Mahabharata declares, “Among all trees, I am the ashvattha” [73]), or else viewed all of the deities as residing in it together (71) (as when the Padma Purana speaks of “God in the form of an ashvattha tree” as being worthy of “the highest worship”, proclaiming that the tree is an enlightened being that has achieved oneness with reality itself [73]). At last, late Vedic commentaries taught that the whole universe was a grand ashvattha tree, which they termed both a “tree of knowledge” (brahmataru) and a “tree of life” (jivanataru); the Maitri and Katha Upanishads, as well as the Bhagavad Gita, identify it as one with the highest vision of brahman—or absolute reality (72–3).

It should not surprise us, then, when we recall that the Buddha gained enlightenment while sitting under this tree (which is therefore, in Buddhist parlance, termed a bodh tree, from the same etymological root as “Buddha”). Beneath the leaves of the sacred fig, he sat not merely under a tree, but under the world tree itself. This explains the serpents that harassed him during that meditation, since world tree stories from all over Eurasia place serpents at the base, but it also reminds us of Norse myth, specifically, in which the well from which Oðin gained wisdom was set at the base of the tree.

One other version of the world tree appears in Indian lore—the Kalpavriksha (variously interpreted as “world tree”, “tree of life”, and “wish-granting tree”). This emerged from the churning of the primordial ocean along with the divine cow Kamadhenu (a motif which will be familiar again to students of Norse lore), and stood on the earth until people began using it to wish for bad things, at which point, depending on the version of the story one hears, Indra took the tree to a paradisiacal garden atop the holy Mt. Meru (recalling the Hungarian tree atop the mountain) to safeguard it from men and demons alike (Dalal, 620).

The Levant—The Tree at the End of the World

The story of the Kalpavriksha bears a certain similarity to another family of world tree stories that link the presence and absence of the tree to the moral and ethical choices of human beings—a family united by the story of Adam and Eve. This emphasis on choice and transgression was natural enough for the Semitic cultures, however, as the world tree concept took a slightly different turn in their myths than in those of the cultures we have examined so far, being associated less with the structure of the cosmos on which the realms are arranged and more with the concept of liminality and the boundaries between the realms.

In the stories of the ancient Egyptians (whose language was closely related to that of their Hebrew and Arab neighbors), the body of the slain god Osiris was concealed in the trunk of a tamarisk tree before being revived by his wife Isis, the tree serving as a waystation between death and life. In some versions of the tale, the tamarisk is replaced by a sycamore. Both trees had long careers later in Semitic myths. Genesis 21:23 tells us that Abraham stopped to plant a tamarisk at Beersheba, where he had earlier dug a well (a connection we have seen before and will return to again), and the sycamore is the tree climbed by Zacchaeus when he hopes to catch a glimpse of Jesus above the heads of the crowd in Luke 19:4. Unquestionably, however, the most notable trees in the Bible appear in Genesis 2–3—the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. So many of the elements we have come to expect of world trees appear here: the serpent at the tree’s base, the intimate connection with the creation of man, the setting within the paradisiacal garden, and the close connection with waters (in the form of the four rivers that flowed out of Eden). But what of the movement between worlds?

In the 3500 years the story has been told, it has come to play a central role in the teachings of no fewer than ten distinct religions, some of which have dozens or hundreds of rival denominations and schools. Accordingly, there are readings of the text that focus on virtually every imaginable angle, and spin it in every conceivable direction. One traditional reading, which Joseph Campbell shared, sees the story precisely as one of movement from the vision of the spiritual to the material world: “ The garden is the place of unity, nonduality, nonduality of male and female, nonduality of man and God, nonduality of good and evil. You eat the duality, and you’re on the way out. So this tree of the [duality], is the tree of the exit.” (Moyers, “Sacrifice and Bliss”)

“Paradise” Tree of Knowledge

(Lucas Cranach, 1530)

In this reading of Genesis, the Fall of Adam and Eve through eating the forbidden fruit represents the descent of consciousness from the plane of undifferentiated awareness—the beholding of the highest or absolute unitary reality symbolized by the Hindus in the ashvattha tree and by the Buddhists in the enlightenment attained by Siddhartha beneath it—into the plane of physical manifestation, on which all things are expressed in dualities. Genesis actually reflects this twice—once as the duality inherent to the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and once in the duality of the Trees of Knowledge and Life (making a fascinating parallelism to the dual accounts of the creation of human beings, with man and woman being made together in a single act in Genesis 1, and separately in two distinct acts in Genesis 2). The tree here is not merely a framework on which the cosmos can be hung, but is itself the mental process required for us to interpret our experience as a reality, similar to Immanuel Kant’s view of space and time not as realities of the world “out there”, but as mental frameworks we impose on the experience of the unknowable “out there” in order to render it comprehensible.

Christian thought adapted this same motif to establish a new world tree in the Cross. Campbell continues:

Now, the tree of coming back to the garden is the tree of immortal life. Where you know that “I and the father are one.” And the two that seem to become one again… Jesus is the fruit of eternal life which was on the second tree in the garden of Eden. And this is exactly the tree under which the Buddha sits… the Buddha under his tree, and Christ hanging on his tree are the same image. They are the same image.

Jesus Tree (Malta)

Indeed, the New Testamentfive times uses the word “tree” to refer to Christ’s Crucifixion (Acts 5:30; 10:39; 13:29; Galatians 3:13; 1 Peter 2:24), all referencing Deuteronomy 21:23 (“Cursed is everyone who is hung on a tree,”) which New Testamentwriters interpreted as a messianic prophecy of the “suffering servant” (cf. Isaiah 52–3). As Campbell observes, the Cross becomes, in their handling, the Tree of Life, which returns consciousness to undifferentiated awareness of ultimate reality and, in doing so, reverses the effect of the Tree of Knowledge. This adds another layer to Paul’s argument for Jesus as the “Second Adam” undoing the work of the first (Romans 5:12–21; 1 Corinthians 15:45) and serves as a key conceptual framework for the doctrine, elaborated in many forms by the Church Fathers, that God had become man that man might become God (cf. Augustine, On the Psalms, 50.2; Athanasius, Against the Aryans, 1.39, 3.34).

This symbolism proved highly suggestive to many European cultures during and after the conversion. The Son’s death upon the Cross to reconcile mankind with the Father suggested to many Germanic writers and artisans Odin’s sacrifice of “himself, to himself,” and caused them to employ much of the same imagery. Early medieval depictions of the Crucifixion from Scandinavia and Central Europe often show the Cross as a tree growing Jesus into itself by the profusion of its leaves, and the Cross often stands at the center of images and narratives as a living character in its own right, as in the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood. A similar tradition has developed in modern India, where one can now sometimes find the ashvattha tree worshipped as Jesus (Haberman, 78), alongside its more traditional representation of Vishnu and Shiva.

The liminal tree thus made a passage between the human and the divine in both Judaism and Christianity, but it was taken up in differing ways in Islam. One branch of Muslim thought likewise made it a conduit. Just as Christ was identified with the Tree of Life, certain schools of Shi’ite Islam that imputed mystical or even divine significance to Muhammad’s daughter Fatima taught that her pre-existent light spirit had been placed by God in the Tree of Life during the time of Adam and Eve, as a reward for her unfailing piety. In this version of the story, it was Eve’s jealousy at Adam’s admiration of Fatima that led her to pick the fruit from the tree in which Fatima resided (Ruffle, 797–9) and thus, for these sects, it was Fatima’s birth that undid the effects of the Fall by regrowing in its fullness the tree that Eve had damaged. Through this connection with the tree, Fatima was taken to be, like Jesus in Christianity, “human, but not in the Adamic sense… fully both a human and a heavenly creation.” (Ibid., 804, 811)

The majority of Muslims hold such views to be heretical in the extreme, however. For them, the world tree is not a gate, but a barrier. The fifty-third sura of the Qur’an (Al-Najm, “The Star”) speaks of the “Sidrat al-Muntahā”—the Lote Tree which stands at the outer boundary of the seventh heaven. Beyond it, even the angels are incapable of approaching the divine throne any farther, and it thus marks the absolute limit of the realm of all that created beings are capable of perceiving or understanding (we recall the words of the Katha Upanishad, which states that there is nothing beyond the ashvattha tree [II.vi.i]). Muhammad is said to have beheld this tree during his famous Night Flight to Jerusalem, when he was led through the ascent by the archangel Gabriel; he beheld the tree bathed in an unparalleled light of beauty and purity, with an angel standing upon every leaf glorifying Allah.

Both the Christian and Islamic world tree concepts informed Bahá’u’lláh, the 19th century Persian nobleman who declared himself the Second Coming of Christ and the Manifestation of God for the present world age. To anchor his claim in the worldviews of both prior religions, he identified himself as “the Lote Tree Beyond Which There is No Passing” (Sadratu’l-Muntahá in the standard Bahá’í spelling ) but, in the process, he took it as a means of joining the human and the divine, rather than separating them. In his person, the tree was incarnate upon Earth to spread the light of God into the world and to make known of Him all that can be known by human beings. Similar to some esoteric teachings on Fatima, he held that all the Manifestations (himself, Muhammad, Jesus, the Buddha, Krishna, and many others) were births in human form of the Tree of Life (Taherzadeh 1976, 80), and he referred to his sons as his “branches” and his wives and daughters as his “leaves” (Liya 2004, 55). As the Most Great Branch—his son, ‘AbdulBahá—later explained, the Tree of Life is the Tree of Knowledge as seen from a nondual perspective, and these are thus identical with each other and with the Lote Tree, which, from one perspective, is the limit of what dualistic vision can perceive, and, from the other, is the portal by which nondualistic vision may apprehend divine reality (in this, we may be reminded that the Katha Upanishad holds that there is nothing beyond the ashvattha tree because it is brahman). Drawing on Rumi’s commentary that the branches of the Lote Tree were filled with birds (Sale n.d., 323 notes) (reminiscent, perhaps, of the eagles atop the world trees of Scandinavia and Siberia), Bahá’u’lláh spoke often of the human soul as a bird. Over the last one hundred fifty years, the branches of his teaching have collected approximately five million of these, and they continue to address their prophet in their daily prayers as “the Lote Tree beyond which there is no passing.”

The world tree makes a notable appearance in another great 19th century religious movement. At the very beginning of the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi), the Israelite prophet Lehi has a visionary dream of the Tree of Life (1 Nephi 8). Three chapters later, his son, Nephi, receives instruction from an angel who interprets the dream for him: “I beheld that the rod of iron, which my father had seen, was the word of God, which led to the fountain of living waters, or to the tree of life; which waters are a representation of the love of God; and I also beheld that the tree of life was a representation of the love of God.” (v. 25) In the angel’s equivalence of the tree and the fountain, we cannot help but be reminded of the well at which Oðin gave his eye for wisdom at the base of Yggdrassil (an allegory for the illuminatory seership that raises the dragon force), and the pool used to drown the sacrificial victims beneath the sacred tree at Uppsala. We think, perhaps, also of the emergence of Kalpavriksha from the primordial ocean and of the close relationship between the creator god Brahma, who was represented by the roots of the ashvattha tree, and his daughter/wife the river goddess Saraswati, who governs the domain of wisdom. In all of these we stay close, perhaps, to the symbol we are doubtless meant to recall—that of being baptized into the death of Christ, which occurs upon the tree.

Whether climbed as a ladder to the deepest self, hung heavily as a trellis for the many realms of gods and men, set at the boundary of all life and knowledge as the farthest marker, or used as the instrument of God’s self-sacrifice, the world tree is always set at the most sacred center—that point where a culture’s treasure is, and its heart is also. In this way, the tree fulfills Campbell’s second purpose of myth in presenting an image of the cosmos, but it does much more than this. As Campbell recognized, the function of depicting the order of the universe has long since been transferred from spiritual disciplines to scientific ones. Today, the more important functions of myth are the first and the fourth—” to evoke in the individual a sense of grateful, affirmative awe before the monstrous mystery that is existence” and to “carry the individual through the stages of his life, from birth through maturity through senility to death” in keeping with that awe. It is precisely to fulfill these functions that the great world religions of our day have adapted the tree in rendering it the symbol of life emergent from death, and of the hope of knowledge in the pursuit of spiritual illumination.

Sources:

Cover Image Attribution: FrostZero, 1990

“Background Context and Observation Recording.” Sacred Plants. National Informatics Center: Rajasthan Forest Department.

Campbell, Joseph. (2004). Pathways to Bliss. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Dalal, Roshen. (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin.

Davidson, Hilda Ellis. (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. Routledge.

Haberman, David L. (2013). People Trees: Worship of Trees in Northern India. Oxford University Press USA.

Jung, Carl Gustav. (1964) Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books, Ltd.

Karlson, Karl Johan. (1914). “Psychoanalysis and mythology.” Journal of Religious Psychology 7.2: 137–213.

Kidder, J. Edward. (1964). Early Japanese Art: The Great Tombs and Treasures. D. van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Liya, Sally. (2004). “The Use of Trees as Symbols in the World Religions.” Solas 4: 41–58.

Moyers, Bill. (1988.) “Episode Four: Myth and Sacrifice.” Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth. PBS.

Ruffle, Karen G. (2008). “An Even Better Creation: The Role of Adam and Eve in Shi’i Narratives about Fatima al-Zahra. ProQuest.

Sale, George. (n.d.) The Koran. London: George Routledge and Sons.

Simek, Rudolf. (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. D.S. Brewer.

Taherzadeh, Abid. (1976). The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume 1: Baghdad, 1853–63. Oxford: George Ronald.

Usačiovaitė, E. (1992). “World-Tree in Ornamentation of the Lithuanian Folk Chests.” Symbols of the Ancient Balts. Vilnius: Academia Publishers.

Vélius, N. (1989). The World Outlook of the Ancient Balts. Vilnius: Mintis Publishers.

World tree

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

From Northern Antiquities, an English translation of the Prose Edda from 1847. Painted by Oluf Olufsen Bagge.

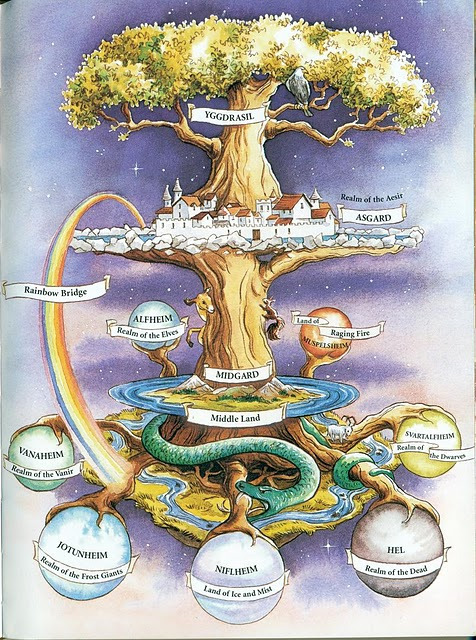

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European religions, Siberian religions, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life.

Specific world trees include világfa in Hungarian mythology, Ağaç Ana in Turkic mythology, Modun in Mongolian mythology, Yggdrasil (or Irminsul) in Germanic (including Norse) mythology, the Oak in Slavic, Finnish and Baltic, Iroko in Yoruba mythology, Kien-Mu or Jian-Mu in Chinese mythology, and in Hindu mythology the Ashvattha (a Sacred Fig).

Contents

[hide]

Norse mythology[edit]

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is the world tree. Yggdrasil is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central and considered very holy. The Æsir go to Yggdrasil daily to hold their courts. The branches of Yggdrasil extend far into the heavens, and the tree is supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations; one to the well Urðarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mímisbrunnr. Creatures live within Yggdrasil, including the harts Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, the giant in eagle-shape Hraesvelgr, the squirrel Ratatoskr and the wyrm Níðhöggr. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the etymology of the name Yggdrasil, the potential relation to the trees Mímameiðr and Læraðr, and the sacred tree at Uppsala.

Siberian culture[edit]

The world tree is also represented in the mythologies and folklore of Northern Asia and Siberia. In the mythology of the Samoyeds, the world tree connects different realities (underworld, this world, upper world) together. In their mythology the world tree is also the symbol of Mother Earth who is said to give the Samoyed shaman his drum and also help him travel from one world to another.

The symbol of the world tree is also common in Tengriism, an ancient religion of Mongols and Turkic peoples.

The world tree is visible in the designs of the Crown of Silla, Silla being one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. This link is used to establish a connection between Siberian peoples and those of Korea.

Mesoamerican culture and Indigenous cultures of the Americas[edit]

- Among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, the concept of "world trees" is a prevalent motif in Mesoamerican mythical cosmologies and iconography. The Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque contains one of the most studied examples of the world tree in architectural motifs of all Mayan ruins. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.[1]

- Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and mythological traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as, or represented by, a ceiba tree, called yax imix che ('blue-green tree of abundance') by the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel.[2] The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree's spiny trunk.[3]

- Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgiaand Fejérváry-Mayer codices.[4] It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

- World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a "water-monster", symbolic of the underworld).

- The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.[5]

- Izapa Stela 5 contains a possible representation of a world tree.

A common theme in most indigenous cultures of the Americas is a concept of directionality (the horizontal and vertical planes), with the vertical dimension often being represented by a world tree. Some scholars have argued that the religious importance of the horizontal and vertical dimensions in many animist cultures may derive from the human body and the position it occupies in the world as it perceives the surrounding living world. Many Indigenous cultures of the Americas have similar cosmologies regarding the directionality and the world tree, however the type of tree representing the world tree depends on the surrounding environment. For many Indigenous American peoples located in more temperate regions for example, it is the spruce rather than the ceiba that is the world tree; however the idea of cosmic directions combined with a concept of a tree uniting the directional planes is similar.

Other cultures[edit]

Although the concept is absent from the Greek mythology, medieval Greek folk traditions and more recent folklore claim that the tree that holds the Earth is being sawed by Kallikantzaroi (commonly translated as goblins).

The world tree is widespread in Lithuanian folk painting, and is frequently found carved into household furniture such as cupboards, towel holders, and laundry beaters.[6][7]

The world tree (Latvian: Austras koks - "Tree of Dawn") also was one of the most important beliefs in Latvian mythology.

Remnants of the world tree concept are also evident within the history and folklore of Ireland's Gaelic past. There are many accounts within early Irish manuscripts of great tribal trees known as Bile being cut down by enemy tribes during times of war. This world tree concept, being strongly Indo-European, was likely to have been a feature of early Celtic culture.[citation needed]

Remnants are also evident in the Kalpavriksha ("wish-fulfilling tree") and the Ashvattha tree of the South Asian religions.

The Yoruba religions worship the Iroko orisha, the first tree to be planted on Earth, used to connect the orishas to the human world.

In Brahma Kumaris religion, the World Tree is portrayed as the "Kalpa Vriksha Tree", or "Tree of Humanity", in which the founder Brahma Baba (Dada Lekhraj) and his Brahma Kumaris followers are shown as the roots of the humanity who enjoy 2,500 years of paradise as living deities before trunk of humanity splits and the founders of other religions incarnate. Each creates their own branch and brings with them their own followers, until they too decline and split. Twig like schisms, cults and sects appear at the end of the Iron Age.[8]

See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World tree. |

- Cassia fistula

- It's a Big Big World, TV-series which takes place at a location called the "World Tree"

- Tree of Life, The Tree of Life is an archetype that is universal, across all cultures"

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ Miller and Taube (1993), p.186.

- Jump up^ Roys 1967: 100

- Jump up^ Miller and Taube, loc. cit.

- Jump up^ Ibid.

- Jump up^ Freidel, et al. (1993)

- Jump up^ Straižys and Klimka, chapter 2.

- Jump up^ Cosmology of the Ancient Balts - 3. The concept of the World-Tree(from the 'lithuanian.net' website. Accessed 2008-12-26.)

- Jump up^ Walliss, John (2002). From World-Rejection to Ambivalence. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 33. ISBN 978-0-7546-0951-3.

References[edit]

- David Abram. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, Vintage, 1997

- Burkert W (1996). Creation of the Sacred: Tracks of Biology in Early Religions. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17570-9.

- Haycock DE (2011). Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.

- Roys, Ralph L., The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967.

External links[edit]

- Cosmology of the Ancient Balts by Vytautas Straižys and Libertas Klimka (Lithuanian.net)

Ancient cosmologies tell of a magnificent World-Tree that grows at the centre of the universe and encompasses all realms of existence: its stem pierces through the world of human affairs, its branches reach high up to the domain of the Gods, upholding the firmament of the heavens and all the stars and planets, while its roots stretch far down into the dark, chthonic Underworld, forming a gateway to the realm of the dead. The image of the World-Tree or Tree of Life is truly universal. It can be found at the centre of archaic cosmological iconography in widely separated cultures all over the world.

One of the oldest recorded accounts of the World-Tree is of Babylonian origin and stems from about 3000 - 4000 BC. This tree stood at the centre of the Universe, which was thought to be somewhere near the ancient city of Eridu at the mouth of the river Euphrates. Its white crystal roots penetrated the primordial waters of the abyss, which were guarded by an amphibious God of wisdom called Ea. He was the source of the waters of life that made the plains fertile. The foliage of the sacred tree was the seat of Zikum, the Goddess of the heavens, while its stem was the holy abode of the Earth-Goddess Davkina and her son Tammuz. Echoes of this imagery can be found in all the mythologies of ancient Mesopotamia.

Writing in the 12th century, the Icelandic scholar, poet, historian and politician Snorri Sturlunson described the Norse version of this cosmic tree in his epic poem known as 'the Edda'. It is hard to tell how much of the symbolism is derived from actual oral accounts of ancient Norse mythology and how much of it is based on the authors' prosaic fancy. The World-Tree of the Eddas seems at any rate to be a compilation of mythic imagery drawn from various sources. The story has been re-told many times, variously embroidered with more or less fancy details, but essentially it goes like this:

Somewhere, in a space beyond space and a time beyond time grows a magnificent, huge tree, who's branches embrace and uphold the heavens, and who's roots reach deep into the Underworld - it is known as the World-Tree Yggdrasil.

Yggdrasil bridges the three great realms of existence: In its midst lies Asgard, the mountainous domain of the Gods, pierced by the stem of the sacred tree. Yggdrasil has three gigantic roots that stretch to all the realms of existence. One reaches into Asa, the second into the realm of the frost giants and the third into Niflheim, the underworld realm of the dead.

Three sacred springs gush forth from beneath the three great roots: From the first flows the spring of wisdom and knowledge, jealously guarded by the hermit Mimir. From the second, springs the well of destiny, guarded by the three Norns, the sisters of fate: Uror (fate), Veroandi (being) and Sculd (necessity) who govern the destinies of human beings. They take care of the tree, water its roots every day, purifying and keeping it alive with the holy waters and the white clay of the sacred spring. The well of destiny is also where the Gods meet for their daily assembly, to settle their differences and decide on their actions. From beneath the third root flows the river of life. Its waters carry the souls of the dead back to be reborn into their next incarnations. But this microcosm what not be complete without the serpent and the eagle, signifying the polarised opposites between the creative and the destructive forces of the Universe. At the very base of the tree lurked the serpent Niddhogg who constantly gnawed away at its roots. Its destructive powers were only kept at bay by an eagle, symbol of the sun, who lived in the upper branchesof the tree from where he continuously warded off the serpent's assaults. Thus, the forces of life and death are kept in equilibrium and the essential life-force of the tree is never damaged.

The image of the World-Tree illustrates the interconnectedness between nature, humans and Gods and forms the basis of an integrated cosmology in which the Gods manifest in nature and humans communicate directly with them through their outer forms. It represents the 'axis-mundi', the immovable central pole of the universe around which all life revolves. In this cosmology, humans and Gods essentially share the same dimension, though on somewhat different levels.

According to the ancient hermetic doctrine 'As Above - So Below', the microcosmic world of human affairs is but a reflection of the macrocosmic world of the Gods. To our ancestors the inherent fertility of nature represented an awesome mystery. The recurrent cycle of the seasons - of blossoming, fruiting, decay - and miraculous rebirth, as seemingly dead branches burst back to life each spring, was seen as a reflection of the regenerative powers of the cosmos itself. Elaborate rituals and ceremonies were held not only to ensure the continued fertility of the land but also to partake spiritually in the cosmic process of regeneration. Trees, with their extremely long lifespan and apparently inexhaustible vigour became the central symbol of such nature based mystery religions. Many fragments of this archaic symbolism have miraculously survived all attempts of eradication and they can still be found in modern religions, customs and folklore, although their original meanings have become much distorted.

The images of the World-Tree and the Tree of Life are closely related and often merge. Sometimes they are replaced by the image of a cosmic mountain, which is also located at the centre of the universe and which likewise generates and sustains all life. All these images symbolically combine the male and female creative powers of the Universe. The obviously phallic connotations of the tree or mountain are identified with the male life-giving, creative force, while the chthonic underworld amidst the roots of the tree or within the crystal cave of the mountain represent the female transformational and regenerative power of the earth womb. Both aspects fused together represent the 'ursymbol' of life, the essence of cyclic existence and eternal self-regeneration.

In Hindu tradition the World-Tree is conceived as being rooted in the heavens and bearing its fruit on earth. All the gods and goddesses, all the elements and cosmic principles are its branches, but each and every one is rooted in Brahman, who is identified with the stem of the sacred tree itself. Perhaps the Banyan tree, one of the most sacred trees of India inspired this concept. The Banyan (Ficus bengalensis) is a truly awe inspiring tree, which spreads over huge areas by sending aerial roots down from its branches. When the arial roots touch the ground they themselves take root and develop into stems. A single tree can comprise a whole forest. Walking among the stems of an old tree is like being in an awesome natural cathedral. The appearance and growing habit of this tree easily suggests the image of a tree rooted in the heavens. It also perfectly symbolizes the idea of multiple Gods and spirits in all their localized aspects essentially all being aspects of the one ultimate source.

It is astounding how similarly the mythological imagery of widely separated cultures expresses the same themes: A creation myth of the Maoris tells of a world-tree, which was the first thing to be formed at the center of the still void universe. It sprouted from an energy vortex, known as the cosmic navel. From the myriad buds of the all-encompassing tree all creation emerged.

Similarly, in Mayan cosmology the World-Tree is a unifying symbol that represents the origin of all existence. It is usually stylised as a maize plant, since maize is the all important staff of life in Maya culture. Other sources however suggest that originally the World-Tree, known as Yax-cheel-cab was identified with the great Kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra), a magnificent species which, when mature, truly seems to reach the heavens. Great buttress-roots at the base of the stem easily suggest the entrance of the Mayan underworld known as Xibalba. Prominent examples of these incredible sacred trees can still be found at practically all ancient Maya sites.

According to a myth from the lake Atitlan region of Guatemala, the World Tree is the progenitor of the manifest universe. At the beginning of time, a great tree stood at the center of the still void Cosmos. It impregnated itself and bore on its branches a multitude of fruits, one for each thing known to humankind: animals, plants, clouds, stars, stones, lightening and even time itself.

Eventually all the fruits became so heavy that the tree could no longer carry them. One by one they fell to the ground and scattered their seeds. Underneath the protective canopy of the tree, they germinated, took root and grew. The Mayans still offer incense and prayers to these ancestral spirits and thus ensure the continued fertility of the land.

A surprisingly similar myth comes from Persia. Here we find references to a 'Tree of all Seeds', which stood at the center of a magical garden known as Pairidaeza, the Persian paradise. This garden was originally associated with the Virgin Goddess Pairidaeza who represented the eternal regenerative womb from which all life proceeds. In her garden the 'Tree of all seeds' grew next to the Tree of Knowledge. One day two birds came to visit the tree, but as one of them attempted to settle in its canopy a thousand branches went crashing to the ground and thus a thousand seeds were scattered. The other bird swiftly gathered up all the seeds and distributed them in various fertile places all over the earth. All the plants and animals with which we share our planet today issued from these seeds.

The Cosmic Tree is commonly described as the source of a special divine substance, a sacred nectar of immortality and ambrosia of the Gods. The ancient holy scriptures known as the 'Rig Vedas' (Indus Valley) refer to this mythical substance as 'Amrita' or 'Soma'. In Persia it was known as Haoma, while the Eddas describe it as 'golden apples stored in Valhalla', which restore the youthfulness of the Gods. The descriptions in the various sacred texts all seem to imply some kind of psychotropic agent and there has been much speculation and debate among scholars and Ethnobotanists regarding the possible botanical identity of this mysterious substance. Numerous theories have been put forward, some believing it to be Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria), others proposing Syrian Rue (Peganum harmala) and various other species as the lost identity of the sacred fruits of the Tree of Life. It is difficult to judge the validity of such hypotheses given that the evidence rests on mythological sources. It is certainly possible that once upon a time one or the other or several different psychotropic plants were indeed identified with these mythical fruits just as the sacred tree itself was variously identified with an actual tree species. Yet tree and fruit need not necessarily share the botanical identity, as their association was perhaps more of a metaphorical nature. So far, despite fervent research, there has been no conclusive result to the inquiry as none of the known hallucinogenic plants satisfactorily complies with the ancient descriptions. Although the question of botanical identity represents an interesting riddle for modern researchers, it seems less important for the spiritual inquirer. The essence of the fruit's esoteric meaning lies just as much in its symbolic significance. Its ultimate spiritual potential is immortal and will be eternally renewed by each and every seeker.

It is interesting to note, that in Mayan as well as in Greek mythology there are references to the Tree of Life or World Tree amidst the signs of the Zodiac, although astronomically there is no such constellation. The mystery is only revealed if one takes into consideration the appearance of the actual night sky itself, which in pre-classical times looked quite different to what can be observed today. Due to a phenomenon known as the 'precession of the equinoxes', caused by the 'wobble' of the earth's path around the sun, the sign of the vernal equinox up to about 4000 BC was Taurus. At the spring equinox, the milky way would appear almost vertical above the observers head, like a giant tree clad in a magnificent cloak of star-flowers, crowned by the sign of Leo and at its root the sign of Aquarius, the Waterbearer. The other constellations were seen as the branches of the World-Tree, and the stars and planets as its fruits. Amidst its roots gushed forth the constellation of Eridanos, the cosmic spring, bearing the waters of life.

The same image is repeated in other mythologies, in which the World Tree is often described as the place where disembodied souls dwell prior to their reincarnation. Underneath the roots of the tree that grows at the centre of the paradisiacal garden, flows the sacred river that carries the waters of life. When their time has come the river of life will carry these souls back to their new incarnations.

In our microcosmic world the same symbolism is often repeated in old churchyards where one can find ancient trees (usually Yews) planted next to a sacred spring. (see Spirit of the Earth - Trees and Fertility, May 2002)

Similarly, in Siberian shamanism the World-Tree represents a cosmic ladder along which spirits and Gods descend or, conversely, along which the shaman can either ascend to the spirit world or climb down into the Underworld. The shaman's drum, which serves as a spirit horse, is made from the wood of the sacred tree. Furthermore, the tree is regarded as a nursery that nurtures the souls of the young shamans until they mature sufficiently to manifest in human form. In the words of the Tungus Shaman Semyonov Semyon:

Up above there is a certain tree where the souls of the shamans are reared, before they attain their powers. And on the boughs of this tree are nests in which the souls lie and are attended. The name of the tree is 'Tuuru. The higher the nest in this tree, the stronger will the shaman be who is raised in it, the more he will know, and the farther he will see. The rim of the shaman's drum is cut from a living larch. The larch is left alive and standing in recollection and honour of the tree Turuu, where the soul of the shaman was raised. Furthermore, in memory of the great tree Tuuru, at each séance the shaman plants a tree with one or more cross-sticks in the tent where the ceremony takes place, and this tree too is called Tuuru. According to our belief, the soul of the shaman climbs up this tree to God when he shamanises. For the tree grows during the rite and invisibly reaches the summit of heaven. (Joseph Campbell, Primitive Mythology)

The Tree of Life or World Tree represents one of the most deeply rooted archetypes of the human psyche and its symbolism still surfaces in the imagery of modern psychotherapy. In terms of Jungian psychology the World-Tree or axis mundi represents the personal 'meridian', the psychological umbilical cord, which connects each individual not only to the divine source (realm of the Gods) but also to the vaults of the unconscious (Underworld). The quest of the mythological hero, who embarks on an adventure to search for the World-Tree, or a sacred mountain at the centre of Universe, is a metaphor for the quest of psychological realignment with one's own inner center and spiritual source. The task of the hero/seeker is to sublimate the cosmic energy that enters his or her being through the realignment with the 'axis mundi'. The journey is usually beset with peril and impending danger for it is a quest of transformation that requires the sacrifice of the ego. In the words of Micea Eliade it is 'a rite of passage, from the illusory to the eternal, from the profane to the sacred and from chaos to cosmos' (Eliade, Myth Of Eternal Return). Thus, the World-Tree is also a symbol of initiation and transcendence. When the hero reaches this centre of the Universe, s/he arrives at the sacred centre of his or her own being.

Footnotes

"The miracle of this flow may be represented in physical terms as a circulation of food substance, dynamically as a streaming of energy, or spiritually as a manifestation of grace. Such varieties of image alternate easily, representing three degrees of condensation of the one life force. An abundant harvest is the sign of God's grace, Gods grace is the food of the soul, the lightening bolt is the harbinger of fertilizing rain and at the same time the manifestation of the released energy of God. Grace, food substance, energy, these pour into the living world and where ever they fail life decomposes into death. The torrent pours from an invisible source the point of entry being the center of the symbolic circle of the universe, the immovable spot of the Buddha legend around which the world may be said to revolve. Beneath this spot is the earth supporting head of the cosmic serpent, the dragon, symbolical of the waters of the abyss, which are the divine life-creative energy and substance of the demiurge, the world generative aspect of immortal being. The Tree of Life, i.e. the universe itself grows from this point."

Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces)

For questions or comments email: kmorgenstern@sacredearth.com