Rough Notes:

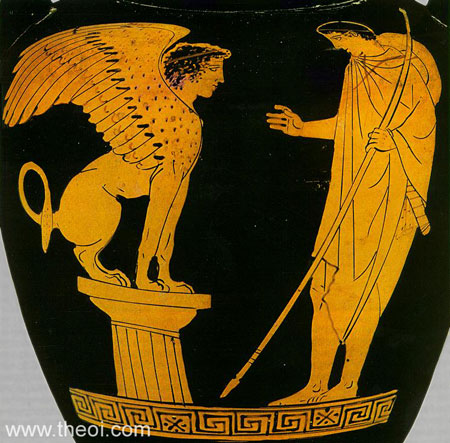

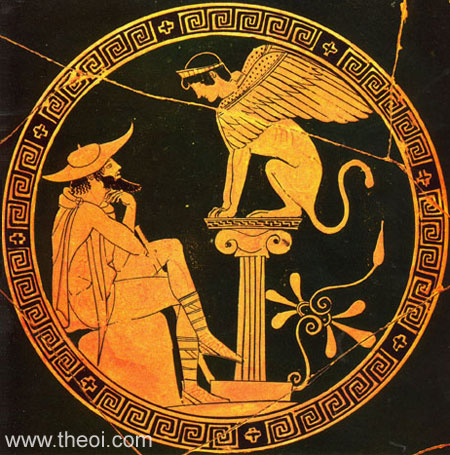

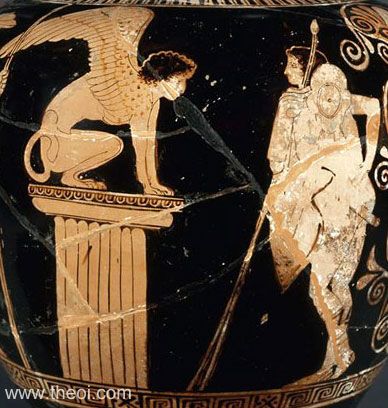

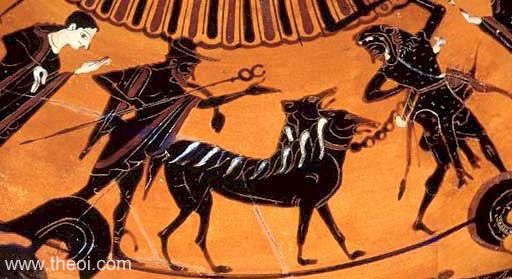

THE SPHINX was a female monster with the body of a lion, the head and breast of a woman, eagle's wings and, according to some, a serpent's tail.

She was sent by the gods to plague the town of Thebes as punishment for some ancient crime, preying on its youths and devouring all who failed to solve her riddle. The regent of Thebes, King Kreon (Creon), offered the throne to the one who would destroy her. Oidipous (Oedipus) took up the challenge, and when he solved the Sphinx's riddle, she cast herself off the mountainside in despair.

Sphinxes were very popular in ancient art. They were employed as sculptural gave stelae upon the tombs of men who died in youth. In archaic vase paintings they often appear amongst a procession of animals and fabulous creatures such as lions and bird-bodied sirens.

FAMILY OF THE SPHINX

PARENTS

[1.1] ORTHOS & KHIMAIRA (Hesiod Theogony 326)

[2.1] TYPHOEUS & EKHIDNA (Apollodorus 3.52, Hyginus Pref & Fabulae 151, Lasus Frag 706A)

[2.2] TYPHOEUS & KHIMAIRA (Scholiast on Hesiod & Euripides)

ENCYCLOPEDIA

SPHINX (Sphinx), a monstrous being of Greek mythology, is said to have been a daughter of Orthus and Chimaera, born in the country of the Arimi (Hes. Theog. 326), or of Typhon and Echidna (Apollod. iii. 5. § 8; Schol. ad Eurip. Phoen. 46), or lastly of Typhon and Chimaera (Schol. ad Hes. and Eurip. l. .c.). Some call her a natural daughter of Laius (Paus. ix. 26. § 2). Respecting her stay at Thebes and her connection with the fate of the house of Laius. The riddle which she there proposed, she is said to have learnt from the Muses (Apollod. iii. 5. § 8), or Laius himself taught her the mysterious oracles which Cadmus had received at Delphi (Paus. ix. 26. § 2). According to some she had been sent into Boeotia by Hera, who was angry with the Thebans for not having punished Lains, who had carried off Chrysippus from Pisa. She is said to have come from the most distant part of Ethiopia (Apollod. l. c. ; Schol. ad Eurip. Phoen. 1760); according to others she was sent by Ares, who wanted to take revenge because Cadmus had slain his son, the dragon (Argum. ad Eurip. Phoen.), or by Dionysus (Schol. ad Hes. Theog. 326), or by Hades (Eurip. Phoen. 810), and some lastly say that she was one on the women who, together with the daughters of Cadmus, were thrown into madness, and was metamorphosed into the monstrous figure. (Schol. ad Eurip. Phoen. 45.)

The legend itself clearly indicates from what quarter this being was believed to have been introduced into Greek mythology. The figure which she was conceived to have had is originally Egyptian or Ethiopian; but after her incorporation with Grecian story, her figure was variously modified. The Egyptian Sphinx is the figure of an unwinged lion in a lying attitude, but the upper part of the body is human. They appear in Egypt to have been set up in avenues forming the approaches to temples. The greatest among the Egyptian representations of Sphinxes is that of Ghizeh, which, with the exception of the paws, is of one block of stone. The Egyptian Sphinxes are often called androsphinges (Herod. ii. 175; Menandr. Fragm. p. 411, ed. Meineke), not describing them as male beings, but as lions with the upper part human, to distinguish them from those Sphinxes whose upper part was that of a sheep or ram. The common idea of a Greek Sphinx, on the other hand, is that of a winged body of a lion, having the breast and upper part of a woman (Aelian, H. A. xii. 7; Auson. Griph. 40 ; Apollod. iii. 5. § 8; Schol. ad Eurip. Phoen. 806). Greek Sphinxes, moreover, are not always represented in a lying attitude, but appear in different positions, as it might suit the fancy of the sculptor or poet. Thus they appear with the face of a maiden, the breast, feet, and claws of a lion, the tail of a serpent, and the wings of a bird (Schol. ad Aristoph. Ran. 1287 ; Soph. Oed. Tyr. 391 ; Athen. vi. p. 253; Palaephat. 7); or the fore part of the body is that of a lion, and the lower part that of a man, with the claws of a vuiture and the wings of an eagle (Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 7). Sphinxes were frequently introduced by Greek artists, as ornaments of architectural and other works. (Paus. iii. 18. § 8, v. 11. § 2; Eurip. Elect. 471.)

In the Boeotian dialect the name was phix (Hes. Theog. 326), whence the name of the Boeotian mountain, Phikion oros. (Hes. Scut. Herc. 33.)

Source: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

ALTERNATE NAME SPELLINGS

Greek Name

Φιξ

Transliteration

Phix

Latin Spelling

Phix

Translation

(Boeotian sp.)

CLASSICAL LITERATURE QUOTES

Hesiod, Theogony 326 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or C7th B.C.) :

"But she [Khimaira (Chimera)] also, in love with Orthos (Orthus), mothered the deadly Sphinx, the bane of the Kadmeians (Cadmeans) [Thebans]."

Lasus, Fragment 706A (from Natale Conti, Mythology) (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric III) (Greek lyric C6th B.C.) :

"The Sphinx was daughter of Ekhidna (Echidna) and Typhon, according to Lasus of Hermione."

Corinna, Fragment 672 (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric IV) (Greek lyric C5th B.C.) :

"Oidipos (Oedipus) killed not only the Sphinx but also the Teumessian fox."

Aeschylus, Sphinx (lost play) (Greek tragedy C5th B.C.) :

The Sphinx was the satyr-play of Aeschylus' Oedipus-trilogy. It told the story of Oidipous' (Oedipus') encounter with the monster.

Aeschylus, Fragment 129 Sphinx (from Aristophanes, Frogs 1287 with Scholiast) (trans. Weir Smyth) (Greek tragedy C5th B.C.) :

"The Sphinx, the watch-dog that presideth over evil days."

Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes 539 ff (trans. Weir Smyth) (Greek tragedy C5th B.C.) :

"[During the war of the Seven against Thebes Parthenopaios (Parthenopaeus) threatens the Thebans with the image of the Sphinx embossed on his shield :] Nor does he take his stand at the gate unboasting, but wields our city's shame on his bronze-forged shield, his body's circular defence, on which the Sphinx who eats men raw is cleverly fastened with bolts, her body embossed and gleaming. She carries under her a single Kadmean (Cadmean) [Theban], so that against this man chiefly our [the Thebans] missiles will be hurled . . . [But] he [Aktor (Actor), a defender of Thebess] will not let in a man who carries on his hostile shield the image of the ravenous, detested beast. That beast outside his shield will blame the man who carries her into the gate, when she has taken a heavy beating beneath the city's walls."

Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes 773 ff :

"For whom have the gods and divinities that share their altar and the thronging assembly of men ever admired so much as they honored Oidipous (Oedipus) then, when he removed that deadly, man-seizing plague (kêr) [i.e. the Sphinx] from our land."

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3. 52 - 55 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd A.D.) :

"While he [Kreon (Creon)] was king, quite a scourge held Thebes in suppression, for Hera sent upon them the Sphinx, whose parents were Ekhidna (Echidna) and Typhon. She had a woman's face, the breast, feet, and tail of a lion, and bird wings. She had learned a riddle form the Mousai (Muses), and now sat on Mount Phikion (Phicium) where she kept challenging the Thebans with it. The riddle was: what is it that has one voice, and is four-footed and two-footed and three-footed? An oracle existed for the Thebans to the effect that they would be free of the Sphinx when they guessed her riddle, so they often convened to search for the meaning, but whenever they came up with the wrong answer, she would seize one of them, and eat him up. When many had died, including most recently Kreon's own son Haimon (Haemon), Kreon announced publicly that he would give both the kingdom and the widow of Laios (Laeus) to the man who solved the riddle. Oidipous (Oedipus) heard and solved it, stating that he answer to the Sphinx's question was man. As a baby he crawls on all fours, as an adult he is two-footed, and as he grows old he gains a third foot in the form of a cane. At this the Sphinx threw herself from the acropolis."

Herodotus, Histories 4. 79. 1 (trans. Godley) (Greek historian C5th B.C.) :

"In the city of the Borysthenites [in Asia Minor] a spacious house, grand and costly . . . all surrounded by Sphinxes and Grypes (Griffins) worked in white marble."

Lycophron, Alexandra 1465 (trans. Mair) (Greek poet C3rd B.C.) :

"Phikian monster [i.e. the Sphinx of Mount Phikion (Phicium)], mouthing darkly her perplexed words."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 9. 26. 2 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd A.D.) :

"Farther on [beyond Thebes, Boiotia (Boeotia)] we come to the mountain from which they say the Sphinx, chanting a riddle, sallied to bring death upon those she caught. Others say that roving with a force of ships on a piratical expedition she put in at Anthedon, seized the mountain I mentioned, and used it for plundering raids until Oidipous (Oedipus) overwhelmed her by the superior numbers of the army he had with him on his arrival from Korinthos (Corinth). There is another version of the story which makes her the natural daughter of Laius (Laeus), who, because he was fond of her, told her the oracle delivered to Kadmos (Cadmus) from Delphoi (Delphi). Now Laius had sons by concubines, and the oracle delivered from Delphoi applied only to Epikaste (Epicaste) and her sons. So when any of her brothers came in order to claim the throne from the Sphinx, she resorted to trickery in dealing with them, saying that if they were sons of Laius they should know the oracle that came to Kadmos. When they could not answer she would punish them with death, on the ground that they had no valid claim to the kingdom or to relationship. But Oidipous came because it appears he had been told the oracle in a dream."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 11. 2 :

"[Amongst the images depicted on the throne in the temple of Zeus at Olympia :] On each of the two front feet are set Theban children ravished by Sphinxes."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 64. 4 (trans. Oldfather) (Greek historian C1st B.C.) :

"A Sphinx, a beast of double form, had come to Thebes and was propounding a riddle to anyone who might be able to solve it, and many were being slain by her because of their inability to do so. And although a generous reward was offered to the man who should solve it, that he should marry Iokaste (Jocasta) and be king of Thebes, yet no man was able to comprehend what was propounded except Oidipous (Oedipus), who alone solved the riddle. What had been propounded by the Sphinx was this : What is it that is at the same time a biped, a triped, and a quadraped? And while all the rest were perplexed, Oidipous declared that the animal proposed in the riddle was ‘man’, since as an infant he is a quadruped, when grown a biped, and in old age a triped, using, because of his infirmity, a staff. At this answer the Sphinx, in accordance with the oracle which the myth recounts, threw herself down a precipice."

Aelian, On Animals 12. 7 (trans. Scholfield) (Greek natural history C2nd A.D.) :

"Egyptian artificers in their sculpture, and the vainglorious legends of Thebes attempt to represent the Sphinx, with her two-fold nature, as of two-fold shape, making her awe-inspiring by fusing the body of a maiden with that of a lion. And Euripides suggests this when he says `And drawing her tail in beneath her lion's feet she sat down.'"

Aelian, On Animals 12. 38 :

"Every painter and every sculptor who devotes himself and has been trained to the practise of his art figures the Sphinx as winged."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 67 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.) :

"The Sphinx, offspring of Typhon, was sent into Boeotia, and was laying waste the fields of the Thebans. She proposed a contest to Creon, that if anyone interpreted the riddle which she gave, she would depart, but that she would destroy whoever failed, and under no other circumstances would she leave the country. When the king heard this, he made a proclamation throughout Greece. He promised that he would give the kingdom and his sister Jocasta in marriage to the person solving the riddle of the Sphinx. Many came out of greed for the kingdom, and were devoured by the Sphinx, but Oedipus, son of Laius, came and interpreted the riddle. The Sphinx leaped to her death. Oedipus received his father's kingdom."

Hyginus, Fabulae 151 :

"From Typhon the giant and Echidna were born . . . the Sphinx which was in Boeotia."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 7. 759 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"The riddle that had baffled earlier brains was solved by Laiades [Oidipous (Oedipus) son of Laius] and headlong down the Carmina [Sphinx] had fallen, her mysteries forgotten."

Seneca, Oedipus 87 ff (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st A.D.) :

"[Oidipous (Oedipus) speaks :] Far from me is the crime and shame of cowardice, and my valour knows not dastard fears . . . The Sphinx, weaving her words in darkling measures, I fled not; I faced the bloody jaws of the fell prophetess and the ground white with scattered bones. And when from a lofty cliff, already hovering over her prey, she prepared her pinions and, lashing her tail like a savage lion, stirred up her threatening wrath, I asked her riddle. Thereupon came a sound of dread; her jaws crashed, and her talons, brooking no delay, eager for my vitals, tore at the rocks. The lot's intricate, guile-entangled words, the grim riddle of the winged beast, I solved.

Why too late dost thou now in madness pray for death? Thou hadst thy chance to die. This sceptre is thy meed of praise, this thy reward for the Sphinx destroyed. That dust, that cursed dust of the artful monster is warring against me still; that pest which I destroyed is now destroying Thebes. [I.e. the land is suffering from drought and pestilence and Oidipous incorrectly blames the ghost of the dead Sphinx]."

Seneca, Oedipus 245 ff :

"Oedipus : Did any fear prevent a pious duty? [i.e. the proper burial of the dead.]

Creon : Aye, the Sphinx and the dire threats of her accursèd chant."

Statius, Thebaid 2. 500 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"At a distance from the city [of Thebes] two hills bear close upon each other with a grudging gulf between; the shadow of a mountain above and leafy ridges of curving woodland shut them in . . . Through the middle of the rocks threads a rough and narrow track, below which lies a plain and a broad expanse of sloping fields. Over against it a threatening cliff rises high, the home of the winged monster [the Sphinx] of Oedipus; here aforetime she stood, fierce uplifting her pallid cheeks, her eyes tainted with corruption and her plumes all clotted with hideous gore; grasping human remains and clutching to her breast half-eaten bones she scanned the plains with awful gaze, should any stranger dare to join in the strife of riddling words, or any traveller confront her and parley with her terrible tongue; then, without more ado, sharpening forthwith the unsheathed talons of her livid hands and her teeth bared for wounding, she rose with dreadful beating of wings around the faces of the strangers; nor did any guess her riddle, till caught by a hero that proved her match, with failing wings--ah! horror!--from the bloody cliff she dashed her insatiate paunch in despair upon the rocks beneath. The wood gives reminder of the dread story: the cattle abhor the neighbouring pastures, and the flock, though greedy, will not touch the fateful herbage; no Dryad choirs take delight in the shade, it ill beseems the sacred rites of the Fauni [Satyroi (Satyrs)], even birds obscene fly far from the abomination of the grove."

Statius, Thebaid 1. 66 :

"By wit of thy foreshowing I [Oidipous (Oedipus)] solved the riddles of the cruel Sphinx."

Suidas s.v. Oidpous (trans. Suda On Line) (Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.) :

"The so-called Sphinx] appeared [at Thebes], a woman hideous and beastly in form, for having got rid of her man and having clenched her hand and having seized some difficult terrain, she would murder those who passed by. So Oidipous (Oedipus), after hatching a clever scheme, joined himself in piracy with her. Then biding his time as he planned, he took her in an ambush, and those with her."

Suidas s.v. Rhapsoidos :

"Rhapsoidos (Rhapsody) : The Sphinx stitching together songs . . . Sophokles [says] : ‘Why, when the watchful dog who wove dark song was here, did you say nothing to free the people?’ He is speaking about the Sphinx."

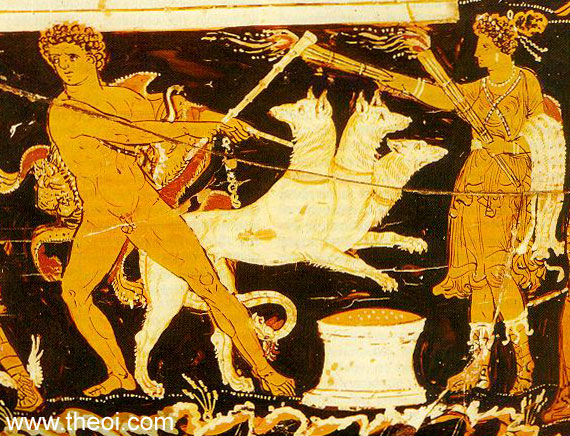

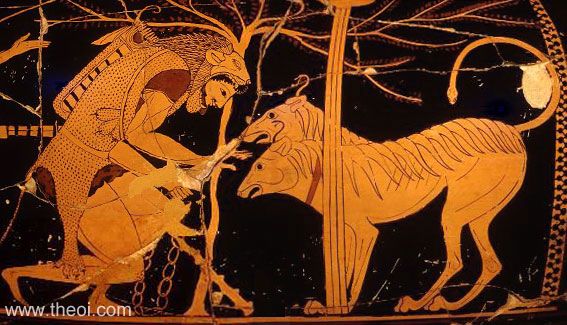

KERBEROS (Cerberus) was the gigantic, three-headed hound of Haides which guarded the gates of the underworld and prevented the escape of the shades of the dead.

Kerberos was depicted as a three-headed dog with a serpent's tail, mane of snakes, and a lion's claws. According to some he had fifty heads although this count may have included the serpents of his mane.

Herakles (Heracles) was sent to fetch Kerberos as one of his twelve labours, a task which he accomplished with the aid of the goddess Persephone.

Kerberos' name perhaps means "Death-Daemon of the Dark" from the ancient Greek words kêr and erebos.

FAMILY OF CERBERUS

PARENTS

[1.1] TYPHOEUS & EKHIDNA (Hesiod Theogony 310, Quintus Smyrnaeus 6.260, Hyginus Pref & Fab 30)

[1.2] EKHIDNA (Bacchylides Frag 5, Ovid Metamorphoses 7.412)

ENCYCLOPEDIA

CE′RBERUS (Kerberos), the many-headed dog that guarded the entrance of Hades, is mentioned as early as the Homeric poems, but simply as "the dog," and without the name of Cerberus. (Il. viii. 368, Od. xi. 623.) Hesiod, who is the first that gives his name and origin, calls him (Theog. 311) fifty-headed and a son of Typhaon and Echidna. Later writers describe him as a monster with only three heads, with the tail of a serpent and a mane consisting of the heads of various snakes. (Apollod. ii. 5. § 12; Eurip. Here. fur. 24, 611; Virg. Aen. vi. 417; Ov. Met. iv. 449.) Some poets again call him many-headed or hundred-headed. (Horat. Carm. ii. 13. 34; Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 678; Senec. Here. fur.784.) The place where Cerberus kept watch was according to some at the mouth of the Acheron, and according to others at the gates of Hades, into which he admitted the shades, but never let them out again.

Source: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

ALTERNATE NAMES

Greek Name

Κυνα του Αιδου

Transliteration

Kuna tou Aidou

Latin Spelling

Cyna Hadum

Translation

Hound of Hades

CLASSICAL LITERATURE QUOTES

Homer, Iliad 8. 366 ff (trans. Lattimore) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"If in the wiliness of my heart I [Athene] had had thoughts like his, when Herakles (Heracles) was sent down to Haides of the Gates, to hale back from Erebos (the Dark) the hound of the grisly death god (Haides Stygeros), never would he have got clear of the steep-dripping water Styx."

[N.B. In Homer the dog is just called "the hound of Haides." Hesiod is the first author to give it the name Kerberos (Cerberus).]

Homer, Odyssey 11. 623 ff (trans. Shewring) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

"[The ghost of Herakles addresses Odysseus in Hades :] ‘He [Eurystheus] once sent me even here [to Haides] to fetch away the hound of Haides, for he thought no task could be more fearsome for me than that. But I brought the hound out of Haides' house and up to earth, because Hermes helped me on my way, and gleaming-eyed Athene.’"

Hesiod, Theogony 310 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or C7th B.C.) :

"Typhaon [Typhoeus] . . . was joined in love to her [Ekhidna (Echidna)] . . . And next again she bore the unspeakable, unmanageable Kerberos (Cerberus), the savage, the bronze-barking dog of Haides, fifty-headed, and powerful, and without pity."

Hesiod, Theogony 769 ff :

"And before them [the halls of Haides and Persephone] a dreaded hound (deinos kunos) [Kerberos (Cerberus)], on watch, who has no pity, but a vile stratagem : as people go in he fawns on all, with actions of his tail and both ears, but he will not let them go back out, but lies in wait for them and eats them up, when he catches any going back through the gates."

Bacchylides, Fragment 5 (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric IV) (Greek lyric C5th B.C.) :

"Once, they say, the gate-wrecking, unconquerable son [Herakles] of thunder-flashing Zeus went down to the house of slender-ankled Persephone to fetch up to the light from Hades the jagged-toothed dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)], son of unapproachable Ekhidna (Echidna). There he perceived the spirits of wretched mortals by the waters of Kokytos (Cocytus), like the leaves buffeted by the wind over the bright sheep-grazed headlands of Ida."

Aristophanes, Peace 315 ff (trans. O'Neill) (Greek comedy C5th to 4th B.C.) :

"[Comedy Play in which Eirene (Irene), goddess of peace, has been trapped in a deep pit :] Let us beware lest the cursed Kerberos (Cerberus) prevent us even from the nethermost hell from delivering the goddess by his furious howling, just as he did when on earth."

Aristophanes, Frogs 468 ff :

"[Comedy-Play in which Aiakos (Aeacus), the gateman of Haides, berates Herakles :] ‘O, you most shameless desperate ruffian, you O, villain, villain, arrant vilest villain! Who seized our Kerberos (Cerberus) by the throat, and fled, and ran, and rushed, and bolted, haling of the dog, my charge!’"

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2, 125 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd A.D.) :

"Herakles asked Pouton (Pluton) [Haides] for Kerberos (Cerberus), and was told to take the hound if he could overpower it without using any of the weapons he had brought with him. He found Kerberos at the gates of Akheron (Acheron), and there, pressed inside his armour and totally covered by the lion's skin, he threw his arms round its head and hung on, despite bites from the serpent-tail, until he convinced the beast with his choke-hold. Then, with it in tow, he made his ascent through Troizenos (Troezen). After showing Kerberos to Eurystheus, he took it back to Haides' realm."

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 122 :

"As a twelfth labour Herakles was to fetch Kerberos (Cerberus) from Haides' realm. Kerberos had three dog-heads, a serpent for a tail, and along his back the heads of all kinds of snakes."

Callimachus, Fragment 515 (trans. Trypanis) (Greek poet C3rd B.C.) :

"The foreigner [Herakles] bringing the monstrous son [Kerberos (Cerberus)] of Ekhidna (Echidna) from below."

Euphorion, Fragments (trans. Page, Vol. Select Papyri III, No. 121 (1)) (Greek epic C3rd B.C.) :

"Behind, under his [Kerberos (Cerberus)] shaggy belly cowering, the serpents that were his tail darted their tongues about his ribs. Within his eyes, a beam flashed darkly. Truly in the Forges or in Meligounis leap such sparks into the air, when iron is beaten with hammers, and the anvil roars beneath might blows,--or up inside smoke Aitna (Etna), lair of Asteropos. Still, he came alive to Tiryns out of Haides, the last of twelve labours, for the pleasure of malignant Eurystheus; and at the crossways of Mideia, rich in barley, trembling women with their children looked upon him."

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 6. 260 ff (trans. Way) (Greek epic C4th A.D.) :

"[Depicted on the shield of Herakles' son Eurypylos (Eurypylus) :] And there, a dread sight even for gods to see, was Kerberos (Cerberus), whom Ekhidna (Echidna, the Loathly Worm) had borne to Typhon [Typhoeus] in a craggy cavern's gloom close on the borders of Eternal Night (Erebos), a hideous monster, warder of the Gate of Haides, home of Wailing, jailer-hound of dead folk in the shadowy Gulf of Doom. But lightly Zeus' son [Herakles] with his crashing blows tamed him, and haled him from the cataract flood of Styx, with heavy-drooping head, and dragged the Dog sore loth to the strange upper air all dauntlessly."

Plato, Republic 588c (trans. Shorey) (Greek philosopher C4th B.C.) :

"One of those natures that the ancient fables tell of, as that of the Khimaira (Chimera) or Skylla (Scylla) or Kerberos (Cerberus), and the numerous other examples that are told of many forms grown together in one."

Strabo, Geography 8. 5. 1 (trans. Jones) (Greek geographer C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"A headland that projects into the sea, Tainaron (Taenarum), with its temple of Poseidon situated in a grove; and secondly, near by, to the cavern through which, according to the myth writers, Kerberos (Cerberus) was brought up from Haides by Herakles."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 35. 10 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd A.D.) :

"[At Hermione in Argolis] are three places which the Hermionians call that of Klymenos (Clymenus, the Famous One) [i.e. of Haides], that of Plouton (Pluton, of Wealth) [Haides], and the Lake Akherousia (Acherusia). All are surrounded by fences of stones, while in the place of Klymenos there is also a chasm in the earth. Through this according to the legend of the Hermionians, Herakles brought up the Hound of Haides [Kerberos (Cerberus)]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 25. 5 - 7 :

"On the promontory [of Tainaron (Taenarum), Lakonia] is a temple like a cave, with a statue of Poseidon in front of it. Some of the Greek poets state that Herakles brought up the Hound of Haides (Haidou kuna) [Kerberos (Cerberus)] here, though there is no road that leads underground through the cave, and it is not easy to believe that the gods possess any underground dwelling where the souls collect.

But Hekataios (Hecataeus) of Miletos gave a plausible explanation, stating that a terrible serpent lived on Tainaron, and was called the Hound of Hades, because any one bitten was bound to die of the poison at once, and it was this snake, he said, that was brought by Herakles to Eurystheus.

But Homer, who was the first to call the creature brought by Herakles the Hound of Haides, did not give it a name or describe it as of manifold form, as he did the Khimaira (Chimera). Late poets gave the name Kerberos, and though in other respects they made him resemble a dog, they say that he had three heads. Homer, however, does not imply that he was a dog, the friend of man, any more than if he called a real serpent the Hound of Hades."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 31. 2 :

"[In the temple of Artemis at Troizenos (Troezen) in Argolis :] . . . are altars to the gods said to rule under the earth. It is here that they say . . . that Herakles dragged up the Hound of Haides [Kerberos (Cerberus)]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 18. 10 - 16 :

"[Illustrated on the throne of the statue of Apollon at Amyklai (Amyclae) near Sparta :] On the left stand Ekhidna (Echidna) and Typhos [Typhoeus], on the right Tritones . . . Next to these have been wrought two of the exploits of Herakles--his slaying of the Hydra, and his bringing up the Hound of Hell (kuna ton Haidou) [Kerberos (Cerberus)]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece5. 26. 7 :

"By the smaller offerings of Mikythos (Micythus) [at Olympia] . . . are some of the exploits of Herakles, including what he did to the Nemeian Lion , the Hydra, the Hound of Hell (kuna tou Haidou) [Kerberos (Cerberus)], and the boar by the river Erymanthos."

Pausanias, Description of Greece 9. 34. 5 :

"Here [on Mount Laphystios in Boiotia], say the Boiotians, Herakles ascended with the hound of Hades (kuna Haidou) [Kerberos (Cerberus)]."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 25. 1 (trans. Oldfather) (Greek historian C1st B.C.) :

"He [Herakles] received a command from Eurystheus to bring Kerberos (Cerberus) up from Hades to the light of day. And assuming that it would be to his advantage for the accomplishment of this Labour, he went to Athens and took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries, Musaios (Musaeus), the son of Orpheus, being at that time in charge of the initiatory rites . . . Herakles then, according to the myths which have come down to us, descended into the realm of Hades, and being welcomed like a brother by Persephone brought Theseus and Peirithous back to the upper world after freeing them from their bonds. This he accomplished by the favour of Persephone, and receiving the dog Kerberos in chains he carried him away to the amazement of all and exhibited him to men."

Plutarch, Life of Nisias 1. 3 (trans. Perrin) (Greek historian C1st to C2nd A.D.) :

"The goddess Kore (Core) [Persephone] who delivered Kerberos (Cerberus) into his [Herakles'] hands."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Preface (trans. Grant) (Roman mythographer C2nd A.D.) :

"From Typhon and Echidna [was born] . . . Cerberus."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 30 :

"He [Herakles (Heracles)] brought from the Lower World for the king to see, the dog Cerberus, offspring of Typhon." - Hyginus, Fabulae 30

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 32 :

"Hercules had been sent for the three-headed dog [Cerberus] by King Eurystheus."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 151 :

"From Typhon the giant and Echidna were born . . . the three-headed dog Cerberus."

Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 251 :

"Those who, by permission of the Parcae (Fates) [Moirai], returned from the lower world . . . Hercules, son of Jove [Zeus], to bring up the dog Cerberus."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 4. 450 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"The Stygian city and the cruel court of swarthy Dis [Haides] . . . she [the goddess Juno-Hera] entered and the threshold groaned under the holy tread. Immediately Cerberus sprang at her with his three heads and gave three barks together."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.500 ff :

"[The Erinys] Tisiphone brought with her poisons too of magic power [to cause madness] : lip-froth of Cerberus, the Echidna's venom, wild deliriums, blindnesses of the brain, and crime and tears, and maddened lust for murder; all ground up, mixed with fresh blood, boiled in a pan of bronze, and stirred with a green hemlock stick."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 7. 412 :

"For that son's [Theseus'] death Medea mixed her poisoned aconite, brought with her long ago from Scythicae's (Scythia's) shores, said to be slobbered by Echidnaea [i.e. Kerberos (Cerberus), son of Ekhidna]. There is a cavern yawning dark and deep, and there a falling track where Hero Tirynthius [Herakles of Tiryns] dragged struggling, blinking, screwing up his eyes against the sunlight and the blinding day, the hell-hound Cerberus, fast on a chain of adamant. His three throats filled the air with triple barking, barks of frenzied rage, and spattered the green meadows with white spume. This, so men think, congealed and, nourished by the rich rank soil, gained poisonous properties. And since they grow and thrive on hard bare rocks the farm folk call them ‘flintworts’--aconites. This poison Aegeus, by Medea's guile, offered to Theseus as his enemy, father to son."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 9. 184 :

"I [Herakles (Heracles) ] faced unafraid Cerberus' triple heads."

Ovid, Metamorphoses 10. 21 ff :

"[Orpheus addresses Haides, king of the underworld :] ‘I have come down not with intent to see the glooms of Tartara, nor to enchain the triple-snaked necks of Medusaeum [Kerberos (Cerberus)].’"

Ovid, Metamorphoses 10. 65 ff :

"His wits were stolen away, like him [unknown man] who saw in dread [Kerberos (Cerberus)] the three-necked hound of Hell with chains fast round his middle neck, and never lost his terror till he lost his nature too and turned to stone."

Ovid, Heroides 9. 37 ff (trans. Showerman) (Roman poetry C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"[Deianeira, wife of Herakles, laments :] ‘My lord is ever absent from me . . . ever pursuing monsters and dreadful beasts. I myself, at home and widowed, am busied with chaste prayers, in torment lest my husband fall by the savage foe; with serpents and with boars and ravening lions my imaginings are full, and with hounds three-throated [i.e. Kerberos (Cerberus)] hard upon the prey.’"

Ovid, Heroides 9. 87 ff :

"[Herakles] told of the deeds . . . Cerberus, branching from one trunk into a three-fold dog, his hair inwoven with the threatening snake."

Virgil, Aeneid 6. 417 ff (trans. Day-Lewis) (Roman epic C1st B.C.) :

"Huge Cerberus, monstrously couched in a cave confronting them, made the whole region echo with this three-throated barking. The Sibyl, seeing the snakes bristling upon his neck now, threw him for bait a cake for honey and wheat infused with sedative drugs. The creature, crazy with hunger, opened its three mouths, gobbled the bait; then its huge body relaxed and lay, sprawled out on the ground, the whole length of its cave kennel. Aeneas, passing its entrance, the watch-dog neutralize, strode rapidly from the bank of that river [Styx] of no return."

Virgil, Georgics 4. 471 ff (trans. Fairclough) (Roman bucolic C1st B.C.) :

"Stirred by his [Orpheus'] song, up from the lowest realms of Erebeus came the unsubstantial shades . . . Still more: the very house of Death and deepest abysses of Tartarus were spellbound, and the Eumenides [Erinyes] with livid snakes entwined in their hair; Cerberus stood agape and his triple jaws forgot to bark."

Propertius, Elegies 3. 5 (trans. Goold) (Roman elegy C1st B.C.) :

"Cerberus guards the cave of hell with his three throats."

Propertius, Elegies 3. 18 :

"Hither [to Haides] all shall come, hither the highest and the lowest class: evil it is, but it is a path that all must tread; all must assuage the three heads of the barking guard-dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] and embark on the grisly greybeard's [Kharon's (Charon's)] boat that no one misses."

Propertius, Elegies 4. 5 :

"May your spirit find no peace with your ashes, but may avenging Cerberus terrify your vile bones with hungry howl."

Propertius, Elegies 4. 7 :

"Spurn not the dreams that come through the Righteous Gate [from the dead]: when righteous dreams come, they have the weight of truth. By night we [the ghosts of the dead] drift abroad, night frees imprisoned Shades, and even Cerberus casts aside his chains and strays."

Propertius, Elegies 4. 9 :

"Only to one mortal [Herakles] has the Stygian darkness become light and Cerberus has howled to find himself dragged off against the will of Dis [Haides]?"

Propertius, Elegies 4. 11 :

"Let fierce Cerberus rush at no Shades today, but let his chain hang slack from a silent bolt."

Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3. 17 (trans. Rackham) (Roman rhetorician C1st B.C.) :

"Orcus [Haides] is also a god; and the fabled streams of the lower world, Acheron, Cocytus and Pyriphlegethon, and also Charon and also Cerberus are to be deemed gods. No, you say, we must draw the line at that; well then, Orcus is not a god either."

Seneca, Hercules Furens 46 ff (trans. Miller) (Roman tragedy C1st A.D.) :

"[Hera complains about Herakles :] ‘Nor is earth vast enough for him [Herakles (Heracles)]; behold, he has broken down the doors of infernal Jove [Haides], and brings back to the upper world the spoils of a conquered king [i.e. the hound Kerberos (Cerberus)]. I myself saw, yes, saw him, the shadows of nether night dispersed and Dis [Haides] overthrown, proudly displaying to his father [Zeus] a brother's spoils. Why does he not drag forth, bound and loaded down with fetters, Pluto [Haides] himself, who drew a lot equal to Jove's [Zeus']? Why does he not lord it over conquered Erebus and lay bare the Styx? It is not enough merely to return; the law of the shades has been annulled, a way back has been opened from the lowest ghosts, and the mysteries of dread Death lie bared. But he, exultant at having burst the prison of the shades, triumphs over me, and with arrogant hand leads through the cities of Greece that dusky hound. I saw the daylight shrink at sight of Cerberus, and the sun pale with fear; upon me, too, terror came, and as I gazed upon the three necks of the conquered monster I trembled at my own command.’"

Seneca, Hercules Furens 598 & 782 ff :

"[Herakles upon returning with Kerberos (Cerberus) describes his journey to the underworld :] ‘Whoever [of the gods] from on high looks down on things of earth, and would not be defiled by a strange, new sight, let him turn away his gaze, lift his eyes to heaven, and shun the portent. Let only two look on this monster [Kerberos (Cerberus)]--him who brought and her who ordered it. To appoint me penalties and tasks earth is not broad enough for Juno's [Hera's] hate. I have seen places unapproached by any, unknown to Phoebus [the sun], those gloomy spaces which the baser pole hath yielded to infernal Jove [Haides]; and if the regions of the third estate pleased me, I might have reigned. The chaos of everlasting night, and something worse than night, and the grim gods and the fates--all these I saw and, having flouted death, I have come back. What else remains? I have seen and revealed the lower world. If aught is left to do, give it to me, O Juno [Hera]; too long already dost thou let my hands lie idle. What dost thou bid me conquer?’

[Amphitryon addresses Theseus :] ‘. . . Unfold his heroic deeds in order; tell how long a way leads to the gloomy shades, and how the Tartarean dog bore his galling bonds.’

[Theseus :] ‘Next after this [the boat of Kharon (Charon)] there appears the palace of greedy Dis [Haides]. Here the savage Stygian dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] frightens the shades; tossing back and forth his triple heads, with huge bayings he guards the realm. Around his head, foul with corruption, serpents lap, his shaggy man bristles with vipers, and in his twisted tail a long snake hisses. His rage matches his shape. Soon as he feels the stir of feet he raises his head, rough with darting snakes, and with ears erect catches at the onsped sound, wont as he is to hear even the shades. When [Herakles] the son of Jove stood closer, within his cave the dog crouches hesitant and feels a touch of fear. Then suddenly, with deep bayings, he terrifies the silent places; the snakes hiss threateningly along all his shoulders. The clamour of his dreadful voice, issuing from triple throats, fills even the blessed shades with dread. Then from his left arm the hero looses the fierce-grinning jaws, thrusts out before him the Cleonaean head and, beneath that huge shield crouching, plies his mighty club with victorious right hand. Now here, now there, with unremitting blows he whirls it, redoubling the strokes. At last the dog, vanquished ceases his threatenings and, spent with struggle, lowers all his heads and yields all wardship of his cavern. Both rulers [Haides and Persephone] shiver on their throne, and bid lead the dog away. Me also [Theseus trapped in Haides] they give as boon to Alcides' prayer.

‘Then, stroking the monster's sullen necks, he binds him with chains of adamant. Forgetful of himself, the watchful guardian of the dusky realm droops his ears, trembling and willing to be led, owns his master, and with muzzle lowered follows after, beating both his sides with snaky tail. But when he came to the Taenarian borders, and the strange gleam of unknown light smote on his eyes, though conquered he regained his courage and in frenzy shook his ponderous chains. Almost he bore his conqueror away, back dragging him, forward bent, and forced him to give ground. Then even to my aid Alcides [Herakles] looked, and with our twofold strength we drew the dog along, mad with rage and attempting fruitless war, and brought him out to earth. But when he saw the bright light of day and viewed the clear spaces of the shining sky, black night rose over him and he turned his gaze to ground, closed tight his eyes and shut out the hated light; backward he turned his face and with all his necks sought the earth; then in the shadow of Hercules he hid his head.’"

Seneca, Hercules Furens 984 ff :

"Cruel Tisiphone [one of the Erinyes (Furies)] . . . since the dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] was stolen away [by Herakles] has blocked the empty gate [of Haides] with her outstretched torch."

Seneca, Hercules Furens 1107 ff :

"Fierce Cerberus, crouching in his lowest cave, his necks still bound with chains."

Seneca, Oedipus 160 ff :

"[Drought and pestilence ravage the city of Thebes :] They have burst the bars of abysmal Erebus, the throng of sisters with Tartarean torch [i.e. the Erinyes, (Furies)] . . . Dark Mors (Death) [Thanatos], death opens wide his greedy, gaping jaws and unfolds all his wings . . . Nay more, they say that the dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] has burst his chains of Taenarian iron, and is wandering through our fields; that the earth has rumbled; that ghosts go stealing through the groves, larger than mortal forms."

Seneca, Oedipus 559 ff :

"[The Theban seer Teiresias (Tiresias) performs the rites of necromancy :] Then he summons the spirits of the dead, and thee who rulest the spirits [Haides], and him [Kerberos (Cerberus)] who blocks the entrance to the Lethaean stream; o'er and o'er and o'er he repeats a magic rune, and fiercely, with frenzied lips, he chants a charm which either appeases or compels the flitting ghosts . . . the whole place was shaken and the ground was stricken from below . . . blind Chaos is burst open, and for the tribes of Dis [Haides] a way is given to the upper world . . . in mad rage three-headed Cerberus shook his heavy chains."

Seneca, Phaedra 222 ff :

"Trust not in Dis [Haides]. Though he bar his realm, and though the Stygian dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] keep guard o'er the grim doors, Theseus alone finds out forbidden ways."

Seneca, Phaedra 843 ff :

"Alcides [Herakles] . . . when he dragged the dog [Kerberos (Cerberus)] by violence out of Tartarus, brought me [Theseus], too, along with him to the upper world."

Seneca, Troades 402 ff :

"Taenarus and the cruel tyrant's [Haides] kingdom and Cerberus, guarding the portal of no easy passage."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 3. 224 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"[The Titan] Coeus in the lowest pit [of Tartaros] burst the adamantine bonds and trailing Jove's [Zeus'] fettering chains . . . conceives a hope of scaling heaven, yet though he repass the rivers and the gloom [Kerberos (Cerberus)] the hound of the Furiai (Furies) [Erinyes] and the sprawling Hydra's crest [the two guardians of Haides] repel him."

Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 6. 110 ff :

"Baying [of Hounds] loud as that which rings at the grim gate of Dis [Haides] [i.e. the bark of Kerberos, Cerberus] or from Hecate's escort to the world above."

Statius, Thebaid 2. 27 (trans. Mozley) (Roman epic C1st A.D.) :

"Cerberus lying on the murky threshold perceived them, and reared up with all his mouths wide agape, fierce even to entering folk; but now his black neck swelled up all threatening, now had he torn and scattered their bones upon the ground, had not the god [Hermes] with branch Lethaean soothed his bristling frame and quelled with threefold slumber the steely glare."

Statius, Thebaid 2. 52 ff :

"The baying of death's tri-formed warder [Kerberos (Cerberus)] has scared the rustics from the fields [around the entrance to Haides at Tainaron]."

Statius, Thebaid 4. 410 ff :

"[Teiresias (Tiresias) performs the rites of nekromankia summoning ghosts from the underworld :] ‘Nor let Cerberus interpose his heads, and turn aside the ghosts that lack the light.’"

Statius, Thebaid 8. 53 ff :

"Fierce Alcides [Herakles] [provoked Haides], when the iron threshold of Cerberus' gate fell silent, its guardian removed."

Statius, Silvae 2. 1. 183 ff (trans. Mozley) (Roman poetry C1st A.D.) :

"Lay aside thy fears [for the beloved dead], and be no more in dread of threatening Letus (Death) [Thanatos]: Cerberus with triple jaws will not bark at him."

Statius, Silvae 2. 1. 228 ff :

"Neither the ferryman [Kharon (Charon)] nor the comrade [the Hydra] of the cruel beast [Kerberos (Cerberus)] bars the way [to the Underworld] to innocent souls."

Statius, Silvae 3. 3. 21 ff :

"Tis a happy shade that is coming, ay, too happy, for his son laments him. Avaunt, ye hissing Furiae (Furies) [Erinyes], avaunt the threefold guardian [Kerberos (Cerberus)]! Let the long road lie clear for the peerless spirits."

Statius, Silvae 5. 3. 260 ff :

"But do ye, O monarchs of the dead and thou, Ennean Juno [Persephone], if ye approve my prayer [provide a peaceful journey for the soul of my dead father] . . . let the warder of the gate [Kerberos (Cerberus)] make no fierce barking."

Apuleius, The Golden Ass 1. 15 ff (trans. Walsh) (Roman novel C2nd A.D.) :

"At that moment, as I recall, the earth yawned open [by the power of witches]. I caught a glimpse of Tartarus deep below, and of Cerberus waiting to make a meal of me to relive his hunger."

Apuleius, The Golden Ass 6. 19 ff :

"[Psykhe (Psyche) is given instructions for her journey down into the underworld :] When you have crossed the river [Akheron (Acheron)] and have advanced a little further, some aged women weaving at the loom will beg you to lend a hand for a short time. But you are not permitted to touch that either, for all these and many other distractions are part of the ambush which Venus [Aphrodite] will set to induce you to release one of the cakes from your hands. Do not imaging that the loss of a mere barley cake is a trivial matter, for if you relinquish either of them, the daylight of this world above will be totally denied you. Posted there is [Kerberos (Cerberus)] a massive hound with a huge, triple-formed head. This monstrous, fearsome brute confronts the dead with thunderous barking, though his menaces are futile since he can do them no harm. He keeps constant guard before the very threshold and the dark hall of Proserpina [Persephone], protecting that deserted abode of Dis [Haides]. You must disarm him by offering him a cake as his spoils. Then you can easily pass him, and gain immediate access to Proserpina herself . . . When you have obtained what she gives you, you must make your way back, using the remaining cake to neutralize the dog's savagery."

ANCIENT GREEK ART

SOURCES

GREEK

- Homer, The Iliad - Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Homer, The Odyssey - Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Hesiod, Theogony - Greek Epic C8th - 7th B.C.

- Greek Lyric IV Bacchylides, Fragments - Greek Lyric C5th B.C.

- Aristophanes, Frogs - Greek Comedy C5th - 4th B.C.

- Aristophanes, Peace - Greek Comedy C5th - 4th B.C.

- Plato, Republic - Greek Philosophy C4th B.C.

- Apollodorus, The Library - Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Callimachus, Fragments - Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

- Greek Papyri III Euphorion, Fragments - Greek Epic C3rd B.C.

- Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History - Greek History C1st B.C.

- Strabo, Geography - Greek Geography C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece - Greek Travelogue C2nd A.D.

- Plutarch, Lives - Greek Historian C1st - 2nd A.D.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy - Greek Epic C4th A.D.

ROMAN

- Hyginus, Fabulae - Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses - Latin Epic C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Ovid, Heroides - Latin Poetry C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

- Virgil, Aeneid - Latin Epic C1st B.C.

- Virgil, Georgics - Latin Bucolic C1st B.C.

- Propertius, Elegies - Latin Elegy C1st B.C.

- Cicero, De Natura Deorum - Latin Rhetoric C1st B.C.

- Seneca, Hercules Furens - Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Oedipus - Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Phaedra - Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Troades - Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Valerius Flaccus, The Argonautica - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Statius, Thebaid - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Statius, Silvae - Latin Poetry C1st A.D.

- Apuleius, The Golden Ass - Latin Novel C2nd A.D.

OTHER SOURCES

Other references not currently quoted here: Euripides Heracles 25 & 611.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A complete bibliography of the translations quoted on this page.

Rough Notes:

Universal Myths and Symbols: Animal Creatures and Creation

by

Pedro Mendia-Landa

Contents of Curriculum Unit 98.02.05:

- Narrative

- Myth, Folklore, and Legends

- Creation Myths

- Mythological animals and creatures

- Animals in diverse mythologies

- The Phoenix

- Methods

- Sample lessons and guidelines

- list of recommended stories

- Electronic resources

- Bibliography

- Teacher and student resources

- appendix A

To Guide Entry

Mythology and mythological ideas permeate all languages, cultures and lives. Myths affect us in many ways, from the language we use to how we tell time; mythology is an integral presence. The influence mythology has in our most basic traditions can be observed in the language, customs, rituals, values and morals of every culture, yet the limited extent of our knowledge of mythology is apparent. In general we have today a poor understanding of the significance of myths in our lives. One way of studying a culture is to study the underlying mythological beliefs of that culture, the time period of the origins of the culture’s myths, the role of myth in society, the symbols used to represent myths, the commonalties and differences regarding mythology, and the understanding a culture has of its myths. Such an exploration leads to a greater understanding of the essence of a culture.

As an elementary school teacher I explore the role that mythology plays in our lives and the role that human beings play in the world of mythology. My objective is to bring to my students’ attention stories that explore the origins of the universe and the origins of human kind, and to encourage them to consider the commonalties and differences in the symbols represented in cross-cultural universal images of the creation of the world.

I begin this account of my unit by clarifying the differences between myth, folklore, and legend, since they have been at times interchangeably and wrongly used. I proceed looking at what a myth is and the role that mythology has played in history. Next I discuss the different approaches of attempting to describe the parallelism among myths from cultures vastly separated by distance. This is followed by a look at different creation myths and a discussion of the commonalties amongst such myths. I propose a renewal of the study of mythology in today’s curriculum as a return to the “shared heritage of ancestral memories”, as represented and taught through the use of mythology. I continue by looking at how such renewal can take place by studying the use of symbols in mythology and the meaning myths acquire with the passing of time. In my overview of mythology, the examples I will present are those of universally present myths related to the creation of the world, and of mythological creatures. Their origins, their symbolism through the ages, the role they play in teaching myth, the representation of myth in other cultures, in the arts, literature, science, philosophy, and religion will be the areas of study. The Phoenix was chosen for its cross-cultural universality and its parallelism of message across time and space.

I conclude the unit by proposing an outline of study of similar mythological creatures and creation stories which will bring the students to see the presence of myth in our daily lives. This proposed outline could be used in the study of other myths. Such a study may follow this progression: tracing a real event leading into the mythical interpretation and representation of that event, then exploring the hyperbole of the myth within the culture, then studying the use of the created symbolism within the culture, and finally examining cross-cultural commonalties and the ways in which the myth is reflected in the other areas of the compared cultures. It is here that this unit can be best adapted to meet the needs of older students.

Beginning the focus of mythological study at myths of creation allows for further exploration of types of etiological myths. The purpose of these myths is to tell why things are as they are (i.e. why the ants live underground, why the sun and the moon live in the sky, etc.). Broadening the unit with the representational mythology of animals provides me with a focused and concrete method for introducing broader mythological concepts to young children.

In my unit I will explore the topic of mythology through the use of the above outline. The unit will explore myths that are cross-culturally related. This mythological exploration will look at the reasons why cultures believe things to be the way they are. It is not meant to be an extensive listing or study of all the creation myths, but a sampling of the wide diversity of myths. I think students are able to come up with very ingenious responses to some of the same questions that many of those myths try to answer. I would venture to say that these myths of how or why things are as they are will closely match the reasons children think things happen the way they do.

Myth, Folklore, and Legends

The term myth has been wrongly used to mean folklore and legend. ADDIN ENRef Rosenberg (1997) differentiates among them in the following way. A myth is a sacred story from the past which is concerned with the powers who control the human world and the relationship between those powers and human beings. A folk tale is a story which is pure fiction and which does not have a particular time or space. It is usually a symbolic way of presenting the way human beings cope with the world where they live. A legend is a story from the past about a historical individual. These stories are concerned with people, places, and events in history.

Bierlein ( ADDIN ENRef 1994) describes myth as the earliest form of science. The purpose of mythology was to explain how the world was formed and how all came to be. However, myth also explains the essence of why all is, which is philosophy and religion. Both religion and science in partnership provide us with an explanation of the creation of the world. Religion and science promote a cosmic myth which allows an understanding of the universe as well as providing a method for finding meaning in life. Also, a myth is the first written record of the oral tradition based on prehistoric events. This places myth in the realm of history. Bierlein claims that it was and continues to be the basis of morality, governance, and identity. I, however, think this is not the case. My belief is supported by the apparently widely spread ignorance we have of such a rich human heritage of ancestral memories. I feel we have lost touch with their meanings. We have forgotten our human unconscious memory which once was universal in all cultures. Yet mythology is the basis of the understanding of our own existence. Bierlein makes some generalizations of what a myth is. He says that myths are universal among all human beings in all times; deal with events that happened before written history and foresee what is to come; describe realities that go beyond our senses and are what holds us together; are essential in all moral conduct and give meaning to life. As we can see, almost all realms are touched upon in this definition of myth.

Creation Myths

Myths of creation are myths of how the universe began. It is the “how” of the beginning of our solar system, of the making of all creatures and everything that surrounds us. Creation myths can be divided into many different categories according to their explanation of the origins of humans, animals, the universe, etc. Thus, we have myths of creation by Deus Faber (God the maker), by emergence, by sacrifice, by secretion, by thought, by word, from a cosmic egg, from ancestors, from chaos, from clay, from dismemberment of primordial being, from division of primordial unity, from nothing, or as explanation ADDIN ENRef (Leeming). Of these myths some are representative of matriarchal or patriarchal societies. In the myths I have collected we will see the role of animals in the genesis. The myth of creation is emulated and repeated in nature by the yearly seasonal cycles; it is the rebirth of the earth in the spring, or the birth of a baby; it is the work of an artist or the song of a musician. These are all representations of the creation in our everyday lives.

The Greek myth of Eurynome and Ophion is a good point of departure as an example of a matriarchal creationist myth. According to the myth Eurynome rose from the sea as the Great Goddess of all things. Ophion, the great serpent of the water, made love to her and Eurynome turned into a bird and gave birth to the great universal egg of which all creatures were born ADDIN ENRef (Bierlein). At this point in history, when the myth is alive, people describe the beginning of the universe through the eyes of the goddess and her symbols. She is the giver of birth and life.

The woman can be representative of the chaos from which the woman creates life by giving birth to herself. She appears in other cultures under different names such as Yemaya, Spider Woman, Ishtar or Astoreth, Demeter, and many others. She is representative of the moon with its cycles while her body is representative of the earth. From her breasts the earth nourishes its creatures and they return back to the earth to die.

Many symbols have been left behind from many different cultures worldwide that attest to the importance of the goddess-creation myth. These symbols have passed now to belong to the human consciousness ADDIN ENRef (Stein). Some of the symbols that have endured associated with the goddess are the egg, the circle and ellipse, the spiral, the triangle pointing down, as well as labyrinths and mazes.

In the beginning all life came from the sea and many cultures used the mermaid and snake with the sea serpent as its symbols. The animals symbolized the goddess of all life. Later in history in the patriarchal myth of creation, the snake symbolizes the downfall of Eve. The goddess of all things turns into a creature and is killed by men. This animal does appear throughout the history of man; however, it takes many forms and most often is associated with the dark forces.

Cecrops, the founder of Athens, was half snake, half-human who taught the first inhabitants how to read, to write, and to work crafts. The great citadel of Athens is named Cecropia after him.

In the Chinese creation myth it is from the hen’s egg that the universe is created. The yolk becomes the sun and sky and the white becomes the earth and sea. In the egg born at the same time is Pangu, who grew and grew for 18,000 years. His height at his death is said to be the distance from earth to heaven. His body became the mountains, the sun and the moon, the rivers, and the wind.

In the Cherokee myth of creation the role of the animals is an important one They viewed the world at creation as being a sea of water being held by four cords at each of the cardinal points ADDIN ENRef (Mooney, p.239). The animals lived crowded above this in Gâl—lati, wanting to know what was below. The water-beetle, “Beaver’s Grandchild”, offered itself to go down and find out, but not finding anything on the surface dove into the water and brought up some mud which begun growing in all directions forming the earth. Afterwards the birds were sent to see if it was dry, and not finding a place to land they went back. Next, the buzzard was sent and it was when tired from flying that it reached the Cherokee country and began to flap and strike the ground, forming the valleys and the mountains. The other animals, afraid that everything would be mountains, called the buzzard back. The creation of humans in this myth takes place only after the animals and the plants have already been created.

For Native American Indians there were no essential differences between nature and man, as demonstrated in their ability to talk to plants and animals. It is only because of the human aggression and carelessness violating the rights of others that the animals in council join forces against him in the Cherokee myth of “The Origin of Disease and Medicine” (Mooney, p.250). We discover how it is that the animals gathered to talk about what they could do to stop humans from slaughtering them. The social order in which animals live is representative of the way that the Native Americans lived. They lived in tribes, had a chief and townhouses, etc.

Every culture at its foundation had its own interpretation of how the world came about and why things were the way they were. However, many similarities do exist. There are two approaches that attempt to explain the parallels between the myths of vastly separated cultures. The first approach believes the myths were created in a few myth-creating locations and were diffused to other cultures with the passing of time and contact among different cultures. The second approach is a psychological view of mythology that believes myths are products of the human psyche and therefore universal to all human beings.

Mythological animals and creatures

In looking for myths related to mythological creatures there seems to be a pattern as to the roles the animal plays in the myth. This pattern is directly related to the importance given to animals in that culture.

In Greek and Roman mythology most often this role is a secondary or a tertiary one. In the love myth of Cupid and Psyche a direct reference is made as to why ants live underground. According to the story, they fear Venus’ wrath because they helped Psyche to overcome the second of the tasks she needed to perform. The first striking aspect, as I read this and other myths, is how closely they parallel in their trials and tribulations the telling and retelling of folk tales. These myths of why things are motivate the listener to take part and to do comparisons among closely related myths. These stories could be best used at story time or as prompts to the writing of a new myth as the children’s knowledge of myths is developed.

Sometimes it is possible to trace the birth of a myth to a part of the world where it becomes established; other times you can see it migrate from one culture to another; from one time period to the next, modified in different ways and at times with many other added symbolical values that may or may not have been there in their origin. This can be seen with an example such as the origins and myths of the Centaur, the sphinx, Pegasus, etc. The myth is seen in motion. We can study the origins and how it changes, taking other values as it is reinterpreted by other times or other cultures. We can study its influences in other areas of society such as the arts, the sciences, history, religion.

ADDIN ENRef South (1987) assigns mythical and fabulous creatures among five categories based on the use of physical characteristics or form. The first category is that of birds and beasts, next the human-animal composites, followed by creatures of darkness, and finally the fairies and giants. The evil mythological creatures outnumber those that are good. These creatures represent the full range from the completely good creatures such as the Ki-Lin, or Chinese unicorn, to the most evil one such the Windingo, a human flesh-eating-creature of Algonquin myth. Some myths have different associations in different cultures. Here the dragon is a good example. In the eastern cultures the dragon is seen as beneficial and good, while in the West it is associated with evil.

The first appearance of mythological and fabulous creatures in the arts is dated to 3,000 BC ADDIN ENRef (Mode, 1975). However, the creation of the myths would be dated much earlier. It is in Egypt and Mesopotamia that many of these myths have their origins. In ancient Egyptian art we have many representations of human-animal beings, especially animal deities with human bodies. From Mesopotamia we have depictions of such creatures as the Centaur, the Phoenix, human-fish composites, the dragon, etc. All these myths were passed onto the West, at times being modified (as in the case of the Phoenix by the Greeks) and then passed on again undergoing other changes.

Animals in diverse mythologies

African mythology is as diverse as the collection of cultures that encompass it. As the cradle of civilization, it nursed the Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures. Prior to this there were indigenous tribesmen, nomadic in nature, who carried their myths from place to place, influencing those cultures surrounding them. Thus, we can see that there are many similarities across the continent in the stories and traditions.

Although the stories in the suggested reading list are not representative of the wide diversity of African mythology, they do present us with samples of animals as primary characters in creating order and reason out of chaos and accident. They are representative of a type of myth that provides the reader with animals playing different roles according to the culture they originate in. In some of the myths, animals are created before humans, and they take an active role in the genesis of the world.

In the mythology of the Fon, or Dahomean, located in what is nowadays the country of Benin, a bird by the name of Wututu acts as the messenger of Sogbo, who is the chief of thunder pantheon. We can see the important role that the animals play by studying the following two myths: “The Rule of Sky and Earth Delimited” ( ADDIN ENRef Courlander, p.161) where in the search for water Sagbata sends the eagle, the vulture, the cat, and the chameleon to his brother Mevioso to ask for water telling us what they endure, and “Sogbo Becomes Master of the Universe”” (Courlander, p.163) where it is Wututu, Sogbo’s messenger who brings relief to the draught. (If the Wututu bird is killed by accident, a big ceremony must be held in reparation).

Some animals such as the praying mantis are widely regarded as sacred. The praying mantis was credited by the San (Bushmen) with bringing fire to the people after having stolen it from the ostrich. The Pale Fox, from the Dogon tradition, was said to have invented agriculture after stealing seeds from the creator god. After going into refuge in the wilderness he is given credit for being the leader in the expansion of the human civilization. For the Bambara people, located in Mali, the originator of agriculture was an antelope sent from heaven to teach the skills of farming ADDIN ENRef (Willis).

There are also representations of animals which are part of the prime force of creation. As representative of these animals we have one of the most widespread creatures used in African mythology, the serpent (Willis, p.277). Under the names of Chinaweji or Chinawezi in Central and Southern Africa, and Nkongolo in Zaire, the serpent plays a pivotal role.

One of the most popular representations of animals in African mythology is the trickster (please refer to other units in this volume). At times represented by a spider in West and Central Africa and as a hare in southern Africa, it also appears in the form of a tortoise or even that of a jackal.

In the creation myth of the Yoruba tradition, “The Descent from the Sky” ADDIN ENRef (Courlander, p.189), Agemo the chameleon plays an integral part in the power struggle between Olorun, the supreme orisha, ruler over the sky and the earth beneath the sky, and Olokun, female deity of the sea and the marshes, in his quest to make earth where only water and marshes exist. The chameleon outwits Olokun in a match paralleling the Greek tale of Arachne challenging Athena to a weaving competition. In the end, Athena saves Arachne’s life as she turns into a spider.

The roles of animals in American Indian mythology are extensive, and integral to the faith of humans in nature. Thus, we can see the hero in the shape of an animal, or that of a human with animal form changing shape as it wills. Among the legends and myths of such heroes we have Old Man Coyote, Bear Man, Spider Woman, or even the Man-Eagle. There is a blurred alliance between people and animals which is most prevalent with the North Pacific Coast tribes and the Plains Indians.

In the Altaie tradition, located in the mountains of Mongolia, it is two geese that fly over the primordial waters ADDIN ENRef (Leeming, p.7). One of them represents God, and the other the devil.

The Phoenix

The following outline will be used in discussing the Phoenix; it can be modified to study any other mythical or fabulous creature.

- 1- Origins of the myth.

- 2- History of the myth from different cultures.

- 3- Symbolism of the myth around the world and across time.

- 4- Myth viewed from the arts, science, etc.

The Phoenix is the best known of the fabulous birds. It is the mythical bird of Heliopolis, Egypt, the city of the sun. It is a sacred bird with gold and red feathers at time represented by a heron-like or eagle-like bird. It is said to have been born in the sun and to reincarnate itself from its own ashes. It is said to live for 500 years and goes to die to Heriopolis, the temple of the sun, after which it reincarnates itself from its ashes.

The origins of the Phoenix are placed in Arabia though it is later considered the bird of Egypt. Later it was borrowed by the Greeks, Romans, Christian Europe and eventually the rest of the modern world. The western depiction of the Phoenix is sometimes associated with other bird myths of oriental origin such as the anka or the roc from Arabia, the semery of Persia, or the garuda of India. They might have been all related to one another, and to a solar myth or real bird such as an eagle or a heron. It may also be related to the Chinese “feng-huang’. This bird with feathers blending the five colors and call of harmony of the five notes is said to have originated in the sun ADDIN ENRef (Ferguson). The Phoenix also resembles the Japanese Ho-o, a Phoenix-like bird that came to earth with the purpose of doing good deeds.

Over the ages the Phoenix has been called many names. Among them are “ bird of the sun”, “ bird of incense” , “ bird of fire”, “ bird of the second birth”, “the Egyptian bird” ADDIN ENRef (South, p.60). These names are significant in that they are descriptive of a mythical aspect of the fabulous creature.

Some of the explanations of its origins include the possibility of being an astrological symbol for the sun setting and rising. It may also be a representation of a human spirit of immortality. These myths may have originated on the “anting” behavior that some bird species exhibit ADDIN ENRef (Burton). Through the behavior of “anting” the bird controls parasites by allowing ants to walk over its body or for smoke to rise through its feathers. Another scientific explanation of its origins may be in the molting process that some of these birds endure, giving the appearance that the bird is reborn.

All of these explanations are no more than hypotheses and any of them or a combination of them may be the origins of the Phoenix. However, what it is certain is the broad influence and universality that the Phoenix has had on the peoples of the world.

It was first mentioned by Hesiod in the eighth century BC. By his account the myth was well known and had lived for a long time ADDIN ENRef (Broek). A more extensive account of the Phoenix comes to us centuries later via Herodotus in the Fifth century BC. It is in the account of the Phoenix by the Roman senator Monilius that we learn about its genesis. According to his account, the Phoenix lives in Arabia and dies every 540 years on a sweet-smelling nest. From the bones and marrow of the dead Phoenix a worm is born and it becomes the new Phoenix. It is from this myth that the Christian church makes use of sweet-smelling incense and myrrh during burial ceremonies. The smoke may symbolize the raising from the dead and the resurrection of the spirit.

Although we can see some differences in the accounts of each of these Phoenix-like birds, there are prevailing permanent elements that are necessary: the bird lives for a long time (540, 1,000, 1,461, or even 12,994 years according to each of the retellings); reappears soon after its death; through death lives again, and is the bird of the sun ADDIN ENRef (Broek).

The myth of the Phoenix is taken as an influential one in the account by Ovid in the Metamorphoses (43 BC - AD 17). This representation of the Phoenix closely resembles the classical Egyptian benu or purple heron. In the book of the death we learn that the benu symbolized the worship of the sun god of Heliopolis.

According to the Li-Ki (Book of Rituals) there are four animals the Chinese consider to be mystical. Among them we encounter the Phoenix, the tortoise, the dragon and the unicorn. The Chinese Phoenix, Phen-huang, has its origins in the sun and is representative of nature. The Phen-Huang is believed to bring prosperity when it appears and calamity on its departure. The Japanese Phoenix, the Ho-o, is said to be the sun descending to earth as a messenger of goodness.

St. Clement of Rome (ca. AD 90-99) is the first Christian to use the Phoenix as part of the Christian teachings. The Phoenix represents the resurrection of those who serve Christ. It is an image of Christ who after his death rises ADDIN ENRef (South).

It is through these accounts that the first Arabian Phoenix myth is hellenized, romanized and christianized and has come to survive and be part of western culture and extensively depicted by authors and artists.

In its origin in Egyptian culture the Phoenix was a divine being. In Greek and Roman cultures it loses its sacredness and becomes more of a supernatural creature. It became also a symbol of political perfection. In the Christian era the Phoenix became the symbol for the resurrection of the body and of the immortal soul. It appears on funeral stones and sarcophagi, in paintings, churches, stonework, etc. It is seen as a sign of the eastern and western sun, the morning and evening sun, or as the sun of spring and fall. It is also a symbol for resurrection, immortality, eternal youth, justice, and self-suffering among others.

In the arts there are many representations of the Phoenix. One of the most extensive ones is the collection of fifty-five black-and-white plates depicting the Phoenix from a mural of paintings in the Tomb of Irenifer. In the Christian tradition it is also depicted in cathedrals, as well as in innumerable coins, sculptures, seals, etc. In literature, the Renaissance is one of the more prolific eras that representative uses of the Phoenix are made.

The symbolism of the Phoenix is diverse in its origins and in its meanings. The basic association is with the sun and it so appears in most of the interpretations. Its capacity of renewal is also universal. Clearly it stands for the human desire for renewal.

Methods

One of the main goals and objectives in writing this unit is the integration of the district’s content standards in the areas of language arts, social studies, science, and social development through the study of mythology. The literary connections in the curriculum between the subject of mythology and language arts are obvious. This unit’s attempt to integrate the social studies, science, and social development curriculum may not be as clear, yet an important focus of the unit that I hope to get across to the reader.

I focus on four content standards in my aim to create an integrated unit of study on mythology. Though it may be too broad as a goal, many other standards that are not here listed will be required, introduced, used, or touched upon. I have chosen at least one of the standards on reading, writing, social studies and library media, and technology as the core of the unit.

Although the unit can be adapted to meet the needs of diverse learners, I write it with the content standards in mind for social studies and language arts specific in the second grade. The following is a list of the content standards that this unit aims to cover in its duration and the tasks the child should be able to perform.

Social studies performance standards

use a computer to access information compare traits found in family and neighborhoods from another time or place with those of the students identify mountains, lakes, and rivers on a map or a globe locate the seven continents and four oceans

Language arts performance standards for grades K-4

read at least 5 books on the topic of mythology

listen to stories about many different topics and cultures

retell stories in order and in detail

make a special project requiring oral both and written presentation through the use of the writing process (first draft, conference, revision, edit, and final draft)

participate in technology for reading and writing

Social development performance standards for grades K-4

Because the main topic is mythology, what was and continues to be the basis of morality, governance and identity ADDIN ENRef (Bierlein, p.5), the social development standards are at the heart of the unit. Performance standards:

acquire good listening skills

learn about people’s similarities and differences

learn to define and look ahead at consequences.

practice good decision-making skills

suggest laws and the consequences of not obeying them.

Science

Identify different properties that can be used for classification.

Explore living things of long ago

Classify the animal kingdom

Mathematics

Use different representations of the same number.( the children could learn how to write and draw the numbers in the Aztec calendar using the animal symbol associated with each number)

Library Media and Technology

create a product related to the material heard, viewed and/or read

use a self-assessment tool prepared by the teacher/student

Through the unit there will be many opportunities to hear telling and retelling of myths with a morality lesson where the focus of the story can be used as the focus of that particular telling. At other times listening as well as oral skills will be specially targeted as a precursor to improved writing skills. The children will learn about people’s similarities and differences, and they will practice through role playing good decision-making skills.

Even though I have not included listening standards, they are at the very core of the unit for they will represent the continuum from beginning to end of the unit. The children will do retellings based on their reactions to the stories. Later, they will read selections and will develop their own presentations.