-

01of 07

Pegasus

Image:eschu1952/www.freeimages.com One of the most well known mythological horses is Pegasus. Winged horses have been used to symbolize freedom, power and victory in many different cultures. Pegasus is an immortal winged horse of Greek mythology. Pegasus is said to have sprung from the head or body, depending on what version of the myth you read, of Medusa, a mythical Gorgon sister with hair of snakes and a stare that could turn a man to stone. Medusa's head was lopped off by Perseus, a greek hero who was challenged by a

-

02of 07

Unicorn

Unicorn on hilltop. Image Credit:Lucy von HeldééDe Agostini RM /Getty Images Another well known mythical horse-like creature is the unicorn. The unicorn is most often described as a beautiful mythical horse with a single horn in its forehead. They are sometimes depicted as having cloven hooves like a goat or deer. The can come in almost every color, although are most often depicted as being white. The tail or mane hairs, blood, hooves or horns of unicorns are often used in magical or medicinal potions and Harry Potter's wand had a core made of a strand of unicorn

-

03of 07

Hippogriff

Hippogriff (12th century), Ferrara Cathedral, Ferrara (Unesco World Heritage List, 1995), Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Image Credit:De Agostini RM /Getty Images Another magical horse-like creature that we, or at least the fans of Harry Potter will be familiar with is the Hippogriff. The Hippogriff predates the Harry Potter books by a few centuries. It is said to have the head, talons and wings of an eagle with the body of the horse. Legend has it that a wizard bred a mare to an eagle and the result was the Hippogriff. They were used as beasts of burden, much like horses were. The Hippogrif appears in several video games and you can download the Hippogrif

-

04of 07

Kelpies

Image showing both of Andy Scott's Kelpies around sunset in November 2013. Image Credit:Moment /Kit Downey Photography /Getty Images If you watched the movie 'The Water Horse' you'll already know that a kelpie is a mythical horse-like creature that lives in rivers and lakes. From Celtic legend is often described as sturdy pony, white or black in color. They are tricksters, luring unsuspecting people into the water where it eats them. Similar horse-like creatures appear in many different mythologies around the world. Kelpies also appeared as menacing shape-shifters in the Harry Potter stories. If you should happen

-

05of 07

Widow Maker

View of a 32-cent postage stamp, issued in 1995 in the United States, that features an illustration of the fictional folkloric character of Pecos Bill, 1995. Image Credit: Blank Archives /Getty Images Widow Maker's real name was Lightening. The American legend of Peco Bill is an amalgam of many tall tales that had their beginnings around campfires of the old west. He was so named because he could be ridden by no one else but Peco's Bill himself. He so disliked Peco Bill's bride that he bucked her off, resulting in the end of the couple's relationship. This emphasises the need to learn to fall off as safely as possible and of course the need to always wear a helmet because the b

-

06of 07

Bucephalus

Alexander Great taming Bucephalus, 1516-1517, fresco by Giovanni Antonio Bazzi known as Il Sodoma (1477-1549), Agostino Chigi's wedding chamber, Villa Farnesina, Rome, Italy, 16th century. Image Credit: Credit: DEA / A. DE GREGORIO/Getty Images The name Bucephalus means 'head of a bull (or ox)'. It's not clear whether a marking such as a star or blaze on the horse's face looked like a bull, or if the horse had a very large wide head or was bullish in attitude. Bucephalus was tamed by a twelve year old , who showed an impressive display of natural horsemanship. The youngster, who would later be known as Alexander the Great, rode the horse in many battles and when the horse died, he named a city after it.

-

07of 07

Sleipnir

/GettyImages-501586121-5701551d3df78c7d9e63eb86.jpg)

Viking stele from Tjängvide, Alskog, Gotland, Sweden, showing Sleipnir, Odin's horse, the offspring of his brother Loki. From the Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm. Image Credit:CM Dixon/Print Collector/ /Getty Images If you think that keeping four hooves healthy can be difficult be glad you don't own Sleipnir. Sleipnir has eight hooves. The mount of the Norse god Odin, Sleipnir was a heroic horse who was swift, sure footed and could jumpanything.

Sacred bull

Bull heads excavated from Çatalhöyük in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

17th Century sculpture of a Nandi bull in Mysore.

The worship of the Sacred Bull throughout the ancient world is most familiar to the Western world in the biblical episode of the idol of the Golden Calf. The Golden Calf after being made by the Hebrew people in the wilderness of Sinai, was rejected and destroyed by Moses and the Hebrew people after Moses' time upon Mount Sinai (Book of Exodus). In Sumerian mythology, Marduk is the "bull of Utu". In Hinduism, Shiva's steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations, as well as modern mentions in new age cultures.

Contents

[hide]

In prehistorical art[edit]

Aurochs are depicted in many Paleolithic European cave paintings such as those found at Lascaux and Livernon in France. Their life force may have been thought to have magical qualities, for early carvings of the aurochs have also been found. The impressive and dangerous aurochs survived into the Iron Age in Anatolia and the Near East and were worshipped throughout that area as sacred animals; the earliest survivals of a bull worship are at neolithic Çatalhöyük.

The bull was seen in the constellation Taurus by the Chalcolithic and had marked the New Year at springtide by the Bronze Age, for 4000–1700 BCE.

In antiquity[edit]

Mesopotamia[edit]

The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the killing by Gilgamesh and Enkidu of the Bull of Heaven, Gugalanna, first husband of Ereshkigal, as an act of defiance of the gods. From the earliest times, the bull was lunar in Mesopotamia (its horns representing the crescent moon).[1]

Egypt[edit]

Hathor as a cow, wearing her necklace and showing her sacred eye on the Papyrus of Ani.

In Egypt, the bull was worshiped as Apis, the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. A long series of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god's priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and encased in a giant sarcophagus. A long sequence of monolithic stone sarcophagi were housed in the Serapeum, and were rediscovered by Auguste Mariette at Saqqara in 1851. The bull was also worshipped as Mnevis, the embodiment of Atum-Ra, in Heliopolis. Ka in Egyptian is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull.

Eastern Anatolia[edit]

We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary at Çatalhöyük in eastern Anatolia. The sacred bull of the Hattians, whose elaborate standards were found at Alaca Höyük alongside those of the sacred stag, survived in Hurrian and Hittite mythology as Seri and Hurri ("Day" and "Night"), the bulls who carried the weather god Teshub on their backs or in his chariot and grazed on the ruins of cities.[2]

Crete[edit]

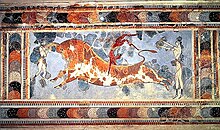

Bulls were a central theme in the Minoan civilization, with bull heads and bull horns used as symbols in the Knossos palace. Minoan frescos and ceramics depict bull-leaping, in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns.

Iran[edit]

The Iranian language texts and traditions of Zoroastrianism have several different mythological bovine creatures. One of these is Gavaevodata, which is the Avestan name of a hermaphroditic "uniquely created (-aevo.data) cow (gav-)", one of Ahura Mazda's six primordial material creations that becomes the mythological progenitor of all beneficent animal life. Another Zoroastrian mythological bovine is Hadhayans, a gigantic bull so large that it could straddle the mountains and seas that divide the seven regions of the earth, and on whose back men could travel from one region to another. In medieval times, Hadhayans also came to be known as Srīsōk (Avestan *Thrisaok, "three burning places"), which derives from a legend in which three "Great Fires" were collected on the creature's back. Yet another mythological bovine is that of the unnamed creature in the Cow's Lament, an allegorical hymn attributed to Zoroaster himself, in which the soul of a bovine (geush urvan) despairs over her lack of protection from an adequate herdsman. In the allegory, the cow represents humanity's lack of moral guidance, but in later Zoroastrianism Geush Urvan became a yazata representing cattle. The 14th day of the month is named after her and is under her protection.

South Asia[edit]

Bulls also appear on seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Nandi appears in Hindu mythology as the primary vehicle and the principal gana (follower) of Shiva.

Cyprus[edit]

In Cyprus, bull masks made from real skulls were worn in rites. Bull-masked terracotta figurines[3] and Neolithic bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus.

Levant[edit]

The Canaanite (and later Carthaginian) statue to which sacrifices were burnt, either as a deity or a type of sacrifice - Moloch - was referred to as a horned man, and likened to Cronus by the Romans. There may be a connection between sacrifice to the Cretan horned man Minotaur and Cronus' himself. Both Baʿal and El were associated with the bull in Ugaritic texts, as it symbolized both strength and fertility.[4]

Cronus' son Zeus was raised on Crete in hiding from his father. Having consumed all of his own children (the gods) Cronus is fed a boulder by Zeus (to represent Zeus' own body so he appears consumed) and an emetic. His vomiting of the boulder and subsequently the other gods (his children) in the Titanomachy bears comparison with the volcanic eruption that appears to be described in Zeus' battle with Typhon in the Theogony. Consequently, Cronus may be associated with the eruption of Thera through the myth of his defeat by Zeus. The later association between Canaanite religions in which child sacrifice took place Ezek. 20:25-26 and the association of child sacrifice with a horned god (as potentially on Crete and certainly in Carthage) may also be connected with the Greek myth of sending young men and women to the Minotaur, a bull-headed man.

Exodus 32:4 "He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, 'This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt'."

Nehemiah 9:18 "even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, 'This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!' They committed terrible blasphemies."

Calf-idols are referred to later in the Tanakh, such as in the Book of Hosea,[5] which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures.

Solomon's "Molten Sea" basin stood on twelve brazen bulls.[6][7]

Young bulls were set as frontier markers at Dan and Bethel, the frontiers of the Kingdom of Israel.

Much later, in Abrahamic religions, the bull motif became a bull demon or the "horned devil" in contrast and conflict to earlier traditions. The bull is familiar in Judeo-Christian cultures from the Biblical episode wherein an idol of the golden calf ((Hebrew: עֵגֶּל הַזָהָב) is made by Aaron and worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of the Sinai Peninsula (Book of Exodus). The text of the Hebrew Bible can be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representing Yahweh himself, perhaps through an association or religious syncretism with Egyptian or Levantine bull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.[citation needed]

Greece[edit]

The Rape of Europa, Jacob Jordaens, 1615

The Rape of Europa, Jean François de Troy, 1716

Among the Twelve Olympians, Hera's epithet Bo-opis is usually translated "ox-eyed" Hera, but the term could just as well apply if the goddess had the head of a cow, and thus the epithet reveals the presence of an earlier, though not necessarily more primitive, iconic view. (Heinrich Schlieman, 1976) Classical Greeks never otherwise referred to Hera simply as the cow, though her priestess Io was so literally a heifer that she was stung by a gadfly, and it was in the form of a heifer that Zeus coupled with her. Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Dionysus was another god of resurrection who was strongly linked to the bull. In a worship hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is also invited to come as a bull, "with bull-foot raging." "Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image," Walter Burkert relates, and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.[8]

For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to the Cretan Bull: Theseus of Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull of Marathon (the "Marathonian bull") before he faced the Minotaur(Greek for "Bull of Minos"), who the Greeks imagined as a man with the head of a bull at the center of the labyrinth. Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family's shame. Living in solitude made the boy wild and ferocious, unable to be tamed or beaten. Yet Walter Burkert's constant warning is, "It is hazardous to project Greek tradition directly into the Bronze age."[9] Only one Minoan image of a bull-headed man has been found, a tiny Minoan sealstone currently held in the Archaeological Museum of Chania.

In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.

Roman Empire[edit]

Tauroctony of Mithras at the British Museum, London.

Bull used as an heraldic crest, here for the Fane family, Earls of Westmorland. (Great Britain, this example 18th or 19th century, but inherited early 17th century from a much earlier use of the idiom by the Neville family).

The religious practices of the Roman Empire of the 2nd to 4th centuries included the taurobolium, in which a bull was sacrificed for the well being of the people and the state. Around the mid-2nd century, the practice became identified with the worship of Magna Mater, but was not previously associated only with that cult (cultus). Public taurobolia, enlisting the benevolence of Magna Mater on behalf of the emperor, became common in Italy and Gaul, Hispania and Africa. The last public taurobolium for which there is an inscription was carried out at Mactar in Numidia at the close of the 3rd century. It was performed in honor of the emperors Diocletian and Maximian.

Another Roman mystery cult in which a sacrificial bull played a role was that of the 1st-4th century Mithraic Mysteries. In the so-called "tauroctony" artwork of that cult (cultus), and which appears in all its temples, the god Mithras is seen to slay a sacrificial bull. Although there has been a great deal of speculation on the subject, the myth (i.e. the "mystery", the understanding of which was the basis of the cult) that the scene was intended to represent remains unknown. Because the scene is accompanied by a great number of astrological allusions, the bull is generally assumed to represent the constellation of Taurus. The basic elements of the tauroctony scene were originally associated with Nike, the Greek goddess of victory.

Macrobius lists the bull as an animal sacred to the god Neto/Neito, possibly being sacrifices to the deity.[10]

Celts[edit]

A prominent zoomorphic deity type is the divine bull. Tarvos Trigaranus ("bull with three cranes") is pictured on reliefs from the cathedral at Trier, Germany, and at Notre-Dame de Paris. In Irish mythology, the Donn Cuailnge plays a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley"), which features the hero Cú Chulainn, which were collected in the seventh century Lebor na hUidre ("Book of the Dun Cow").

Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century, describes a religious ceremony in Gaul in which white-clad druids climbed a sacred oak, cut down the mistletoe growing on it, sacrificed two white bulls and used the mistletoe to cure infertility:[11]

The druids — that is what they call their magicians — hold nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and a tree on which it is growing, provided it is Valonia oak…. Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on the sixth day of the moon….Hailing the moon in a native word that means ‘healing all things,’ they prepare a ritual sacrifice and banquet beneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whose horns are bound for the first time on this occasion. A priest arrayed in white vestmentsclimbs the tree and, with a golden sickle, cuts down the mistletoe, which is caught in a white cloak. Then finally they kill the victims, praying to a god to render his gift propitious to those on whom he has bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe given in drink will impart fertility to any animal that is barren and that it is an antidote to all poisons.[12]

Medieval and modern and other uses[edit]

The practice of bullfighting in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France are connected with the legends of Saturnin of Toulouse and his protégé in Pamplona, Fermin. These are inseparably linked to bull-sacrifices by the vivid manner of their martryrdoms set by Christian hagiography in the third century.

In some Christian traditions, Nativity scenes are carved or assembled at Christmas time. Many show a bull or an ox near the baby Jesus, lying in a manger. Traditional songs of Christmas often tell of the bull and the donkey warming the infant with their breath. This refers (or, at least, is referred) to the beginning of the book of the prophet Isaiah, where he says: "The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib." (Isaiah 1:3)

Taurus (Latin for "the Bull") is one of the constellations of the zodiac, which means it is crossed by the plane of the ecliptic. Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in the northern hemisphere's winter sky. It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to at least the Early Bronze Age when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox. Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of Ancient Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

See also[edit]

- Bulls in Indo-European mythology

- Bucranium

- Bugonia

- Camahueto

- Cattle in religion

- Deer in mythology

- Horned deity

- Mithraism

- Red heifer

- Taurobolium

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ Jules Cashford, The Moon: Myth and Image 2003, begins the section "Bull and cow" pp 102ff with the simple observation, "Other animals become epiphanies of the Moon because they look like the moon.... the sharp horns of a bull or cow were seen to match the pointed curve of the waxing and waning crescents so exactly that the powers of the one were attributed to the other, each gaining the other's potency as well as their own."

- Jump up^ Hawkes and Woolley, 1963; Vieyra, 1955

- Jump up^ Burkert 1985

- Jump up^ Miller, Patrick (2000), Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays, Continuum Int'l Publishing Group, p. 32, ISBN 1-84127-142-X.

- Jump up^ "Hosea 10:5 The people who live in Samaria fear for the calf-idol of Beth Aven. Its people will mourn over it, and so will its idolatrous priests, those who had rejoiced over its splendor, because it is taken from them into exile". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- Jump up^ "1 Kings 7:25 The Sea stood on twelve bulls, three facing north, three facing west, three facing south and three facing east. The Sea rested on top of them, and their hindquarters were toward the center". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- Jump up^ "Jeremiah 52:20 The bronze from the two pillars, the Sea and the twelve bronze bulls under it, and the movable stands, which King Solomon had made for the temple of the LORD, was more than could be weighed". Bible.cc. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- Jump up^ Burkert 1985 pp. 64, 132

- Jump up^ Burkert 1985 p. 24

- Jump up^ Macrobius, Saturnalia, Book I, XIX

- Jump up^ Miranda J. Green. (2005) Exploring the world of the druids. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28571-3. Page 18-19

- Jump up^ Natural History (Pliny), XVI, 95

References[edit]

- Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, 1985

- Campbell, Joseph Occidental Mythology "2.The Consort of the Bull", 1964.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta; Woolley, Leonard: Prehistory and the Beginnings of Civilization, v. 1 (NY, Harper & Row, 1963)

- Vieyra, Maurice: Hittite Art, 2300-750 B.C. (London, A. Tiranti, 1955)

- Jeremy B. Rutter, The Three Phases of the Taurobolium, Phoenix (1968).

- Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and its Remains (NY, Arno Press, 1976) pp. 113–114.

External links[edit]

- An exhibit on the tombs of Alaca Höyük at the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes one example of the bull standards.

- Bull Tattoo Art The image of the bull in tattoo art.

Minotaur

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

|

Minotaur bust, (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

|

|

| Grouping | Mythological creature |

|---|---|

| Parents | Cretan Bull and Pasiphaë |

| Mythology | Greek |

| Region | Crete |

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur (/ˈmaɪnətɔːr/,[1] /ˈmɪnəˌtɔːr/;[2] Ancient Greek: Μῑνώταυρος [miːnɔ̌ːtau̯ros], Latin: Minotaurus, Etruscan: Θevrumineś) is a mythical creature portrayed in Classical times with the head of a bull and the body of a man[3] or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "part man and part bull".[4] The Minotaur dwelt at the center of the Labyrinth, which was an elaborate maze-like construction[5] designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus, on the command of King Minos of Crete. The Minotaur was eventually killed by the Athenian hero Theseus.

The term Minotaur derives from the Ancient Greek Μῑνώταυρος, a compound of the name Μίνως (Minos) and the noun ταύρος "bull", translated as "(the) Bull of Minos". In Crete, the Minotaur was known by the name Asterion,[6] a name shared with Minos' foster-father.[7]

"Minotaur" was originally a proper noun in reference to this mythical figure. The use of "minotaur" as a common noun to refer to members of a generic species of bull-headed creatures developed much later, in 20th-century fantasy genre fiction.

Contents

[hide]

Birth and appearance[edit]

The bronze "Horned God" from Enkomi, Cyprus

After he ascended the throne of the island of Crete, Minos competed with his brothers to rule. Minos prayed to Poseidon, the sea god, to send him a snow-white bull, as a sign of support (the Cretan Bull). He was to kill the bull to show honor to the deity, but decided to keep it instead because of its beauty. He thought Poseidon would not care if he kept the white bull and sacrificed one of his own. To punish Minos, Poseidon made Pasiphaë, Minos's wife, fall deeply in love with the bull. Pasiphaë had craftsman Daedalus make a hollow wooden cow, and climbed inside it in order to mate with the white bull. The offspring was the monstrous Minotaur. Pasiphaë nursed him, but he grew and became ferocious, being the unnatural offspring of a woman and a beast; he had no natural source of nourishment and thus devoured humans for sustenance. Minos, after getting advice from the oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos' palace in Knossos.[8]

The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. One of the figurations assumed by the river spirit Achelous in seducing Deianira is as a man with the head of a bull, according to Sophocles' Trachiniai.

From Classical times through the Renaissance, the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth.[9] Ovid's Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not elaborate on which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show the reverse of the Classical configuration, a man's head and torso on a bull's body, reminiscent of a centaur.[10] This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and still figures in some modern depictions, such as Steele Savage's illustrations for Edith Hamilton's Mythology (1942).

Theseus and the Minotaur[edit]

Rhyton in the shape of a bull's head, Heraklion Archaeological Museum; shown here at the Greek pavilion at Expo '88

Androgeus, son of Minos, had been killed by the Athenians, who were jealous of the victories he had won at the Panathenaic festival. Others say he was killed at Marathon by the Cretan Bull, his mother's former taurine lover, which Aegeus, king of Athens, had commanded him to slay. The common tradition is that Minos waged war to avenge the death of his son and won. Catullus, in his account of the Minotaur's birth,[11] refers to another version in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of Androgeos." Aegeus had to avert the plague caused by his crime by sending "young men at the same time as the best of unwed girls as a feast" to the Minotaur. Minos required that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, drawn by lots, be sent every seventh or ninth year (some accounts say every year[12]) to be devoured by the Minotaur.

When the third sacrifice approached, Theseus volunteered to slay the monster. He promised his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful, but would have the crew put up black sails if he was killed. In Crete, Minos' daughter Ariadne fell madly in love with Theseus and helped him navigate the labyrinth. In most accounts she gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. Theseus killed the Minotaur with the sword of Aegeus and led the other Athenians back out of the labyrinth. On the way home, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos and continued. He neglected, however, to put up the white sail. King Aegeus, from his lookout on Cape Sounion, saw the black-sailed ship approach and, presuming his son dead, committed suicide by throwing himself into the sea that is since named after him.[13] This act secured the throne for Theseus.

Etruscan view[edit]

This essentially Athenian view of the Minotaur as the antagonist of Theseus reflects the literary sources, which are biased in favour of Athenian perspectives. The Etruscans, who paired Ariadne with Dionysus, never with Theseus, offered an alternative Etruscan view of the Minotaur, never seen in Greek arts: on an Etruscan red-figure wine-cup of the early-to-mid fourth century Pasiphaë tenderly cradles an infant Minotaur on her knee.[14]

Interpretations[edit]

Theseus fighting the Minotaur by Jean-Etienne Ramey, marble, 1826, Tuileries Gardens, Paris

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in Greek art. A Knossian didrachm exhibits on one side the labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; one of the monster's names was Asterion ("star").

While the ruins of Minos' palace at Knossos were discovered, the labyrinth never was. The enormous number of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the labyrinth myth, an idea generally discredited today.[15]Homer, describing the shield of Achilles, remarked that the labyrinth was Ariadne's ceremonial dancing ground.

Some modern mythologists regard the Minotaur as a solar personification and a Minoan adaptation of the Baal-Moloch of the Phoenicians. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case indicates the breaking of Athenian tributary relations with Minoan Crete.[16]

The Minotaur in the Labyrinth, engraving of a 16th-century AD gem in the Medici Collection in the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence[17]

According to A. B. Cook, Minos and Minotaur are only different forms of the same personage, representing the sun-god of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull. He and J. G. Frazer both explain Pasiphaë's union with the bull as a sacred ceremony, at which the queen of Knossos was wedded to a bull-formed god, just as the wife of the Tyrant in Athens was wedded to Dionysus. E. Pottier, who does not dispute the historical personality of Minos, in view of the story of Phalaris, considers it probable that in Crete (where a bull cult may have existed by the side of that of the labrys) victims were tortured by being shut up in the belly of a red-hot brazen bull. The story of Talos, the Cretan man of brass, who heated himself red-hot and clasped strangers in his embrace as soon as they landed on the island, is probably of similar origin.

A historical explanation of the myth refers to the time when Crete was the main political and cultural potency in the Aegean Sea. As the fledgling Athens (and probably other continental Greek cities) was under tribute to Crete, it can be assumed that such tribute included young men and women for sacrifice. This ceremony was performed by a priest disguised with a bull head or mask, thus explaining the imagery of the Minotaur.

Once continental Greece was free from Crete's dominance, the myth of the Minotaur worked to distance the forming religious consciousness of the Hellene poleis from Minoan beliefs.

Cultural references[edit]

Dante's Inferno[edit]

Dante and Virgil meet the Minotaur, illustration by Gustave Doré

William Blake's image of the Minotaur to illustrate Inferno XII

The Minotaur (infamia di Creti, Italian for "infamy of Crete"), appears briefly in Dante's Inferno, in Canto 12 (l. 12–13, 16–21), where Dante and his guide Virgil find themselves picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the Seventh Circle of Hell.[18]

Dante and Virgil encounter the beast first among the "men of blood": those damned for their violent natures. Some commentators believe that Dante, in a reversal of classical tradition, bestowed the beast with a man's head upon a bull's body,[19] though this representation had already appeared in the Middle Ages.[20]

|

|

In these lines Virgil taunts the Minotaur in order to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by Theseus the Duke of Athens with the help of the monster's half-sister Ariadne. The Minotaur is the first infernal guardian whom Virgil and Dante encounter within the walls of Dis.[21] The Minotaur seems to represent the entire zone of Violence, much as Geryon represents Fraud in Canto XVI, and serves a similar role as gatekeeper for the entire seventh Circle.[22]

Giovanni Boccaccio writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death".[23] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his own commentary,[24][25] compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against oneself) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)."

Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the centaurs (Nessus, Chiron, Pholus, and Nessus) who guard the Flegetonte ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.[26]

Surrealist art and other references[edit]

- From 1933 to 1939, Albert Skira published an avant-garde literary magazine Minotaure, with covers featuring a Minotaur theme. The first issue had cover art by Pablo Picasso. Later covers included work by Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, Max Ernst, and Diego Rivera.

- Picasso made a series of etchings in the Vollard Suite showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.[27]

- The Minotaur appears as the protagonist of Steven Sherill's The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break[28] The character returns in The Minotaur Takes His Own Sweet Time[29]

- The documentary Room 237 suggests that The Shining is a re-telling of the myth of the Minotaur.

- A minotaur, descended from the original mythological figure, appears in the third episode of The Librarians ("And The Horns of a Dilemma"). Golden Axe Foods, an agribusiness firm founded by survivors of the Minoan civilization (the name refers to a symbol of the Minoan monarchy) have imprisoned the minotaur to recreate the Labyrinth in order to maintain their wealth and prosperity. The minotaur itself is presented as a large, bull-headed man in leather garb, who can shapeshift into the form of a muscular biker (Tyler Mane). It is freed when the labyrinth is destroyed, and proceeds to exact revenge upon its captors.

- In a 2011 episode of Doctor Who (series 6) ("The God Complex") The Doctor, Amy and Rory find themselves in a mysterious hotel with rooms and corridors that constantly change to form an endless labyrinth, allowing the minotaur trapped inside to hunt people down one by one with their secret fears...until they give in and are consumed. The minotaur itself is not revealed until the end of the episode

- Minotaurs are common enemies in the God of War series.

- The 2017 verse novel Bull by David Elliot retells the story of the Minotaur in a modern light, paying special attention to Asterion's childhood, relationships between the characters, and other such details never touched on by the original myths.

See also[edit]

- Apis – the Egyptian god is often depicted as a bull, or bull-headed man

- Bull-Leaping Fresco

- Madness and the Minotaur - a 1981 a text adventure game for the TRS-80 Color Computer

- Mahishasura – Buffalo headed Asura

- Minoan Bull-leaper

- Centaur

- Minotaur – a novel by Benjamin Tammuz first published in 1981

- Minotaur – a 2006 horror film

- Molech or Ba'al – worshipped in the Middle East and depicted as a horned man

- Nandi – a bull that serves Lord Shiva in Hindu mythology

- Ox-Head – guardian of the Underworld in Chinese mythology, had a bull head and a human body

- Sarangay – a creature resembling a bull with a huge muscular body and a jewel attached to its ears

- Tauren – a fictional bovine species from the Warcraft franchise modeled after the Minotaur

- Shedu – in Mesopotamian mythology, had a bull body and a human head

- Ushi-oni – a bull-headed monster from Japanese folklore

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ "English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July2013.

- Jump up^ "American English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Jump up^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 34. ISBN 3791321447.

- Jump up^ semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem, according to Ovid, Ars Amatoria 2.24, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo. (noted by J. S. Rusten, "Ovid, Empedocles and the Minotaur" The American Journal of Philology 103.3 (Autumn 1982, pp. 332-333) p. 332.

- Jump up^ In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BC, many visual patterns representing the Labyrinth do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center. See Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, Chapter 1, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, 1990, Chapter 2.

- Jump up^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 31. 1

- Jump up^ The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women fr. 140, says of Zeus' establishment of Europa in Crete: "...he made her live with Asterion the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys."

- Jump up^ "Minotaur | Greek mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- Jump up^ Several examples are shown in Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000.

- Jump up^ Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern. op. cit.

- Jump up^ Carmen 64.

- Jump up^ Servius on Aeneid, 6. 14: singulis quibusque annis "every one year". The annual period is given by J. E. Zimmerman, Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Harper & Row, 1964, article "Androgeus"; and H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Greek Mythology, Dutton, 1959, p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias. The nine-year period appears in Plutarch and Ovid.

- Jump up^ Plutarch, Theseus, 15—19; Diodorus Siculus i. I6, iv. 61; Bibliotheke iii. 1,15

- Jump up^ The wine cup is illustrated in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Mythology (Series The Legendary Past, British Museum / University of Texas at Austin) 2006, fig.29 p. 44 ("early fourth century") (on-line illustration).

- Jump up^ Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not himself believe it; see David McCullough, The Unending Mystery, Pantheon, 2004, p. 34-36. Modern scholarship generally discounts the idea; see Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, p. 42-43, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, p. 1990, p. 25.

- Jump up^ The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. 1911.

- Jump up^ Paolo Alessandro Maffei, Gemmae Antiche, 1709, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Hermann Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, fig. 371, p. 202): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from Classical antiquity".

- Jump up^ The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.

- Jump up^ Inferno XII, Verse Translation by Dr. R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary

- Jump up^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 116–117. ISBN 3791321447.

- Jump up^ The fallen angels, the Erinyes [Furies], and the unseen Medusa were located on the city's defensive ramparts in Canto IX.

- Jump up^ Boccaccio Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine commentary

- Jump up^ Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy, University of Toronto Press, 30 Nov 2009

- Jump up^ Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177-180.

- Jump up^ "Dante Family letters Rossetti Archive". Rossettiarchive.org.

- Jump up^ Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs," Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217-29

- Jump up^ Tidworth, Simon Theseus in the Modern World essay in The Quest for Theseus London 1970 pp244-9 ISBN 0269026576

- Jump up^ O'Grady, Megan (12 December 2002). "Dreaming of Hoofbeats". The New York Times.

- Jump up^ Gurganus, Allan (October 2, 2016). "A Minotaur's in Maintenance in a Tale of Rust Belt America". The New York Times.

References[edit]

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art.

- Percy Jackson's Greek Heroes, Rick Riordan, 2015

External links[edit]

The dictionary definition of Minotaur at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Minotaur at Wiktionary Media related to Minotaur at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Minotaur at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Minotaur at Wikisource

Works related to Minotaur at Wikisource

/pegasussxclg-56a4dbf95f9b58b7d0d99100.jpg)

/GettyImages-494326749-570153445f9b58619533c259.jpg)

/GettyImages-175819927-570152fe5f9b58619533c214.jpg)

/GettyImages-514884083-570158d75f9b58619533dbd9.jpg)

/GettyImages-77929603-5701557c3df78c7d9e63ebff.jpg)

/GettyImages-159618731-570158923df78c7d9e63ffaa.jpg)