Rough Notes:

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. More info.

ARES

Greek Name

Αρης

Transliteration

Arês

Latin Spelling

Ares

Roman Name

Mars

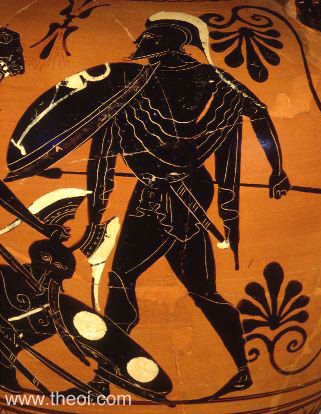

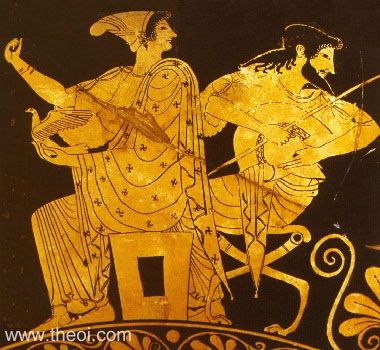

ARES was the Olympian god of war, battlelust, courage and civil order. In ancient Greek art he was depicted as either a mature, bearded warrior armed for battle, or a nude, beardless youth with a helm and spear.

MYTHS

Ares had an adulterous affair with the goddess Aphrodite but her husband Hephaistos trapped the pair in a golden net and humiliated them by calling the rest of the gods to witness. <<More>>

When Aphrodite fell in love with the handsome youth Adonis, the god grew jealous, transformed himself into a boar, and gorged the boy to death as he was out hunting. <<More>>

Ares transformed his daughter Harmonia and her husband Kadmos (Cadmus) of Thebes into serpents and had them carried away to the Islands of the Blessed. <<More>>

The god slew Hallirhothios to avenge the rape of his daughter Alkippe. He was tried at the court of the Areiopagos in Athens but acquitted of murder. <<More>>

Ares apprehended the criminal Sisyphos, an impious man who had dared to kidnap the god of death Thanatos. <<More>>

During the battle between Herakles and Ares’ villianous Kyknos (Cycnus), the god intervened but was wounded by the hero and forced to flee back to Olympos. <<More>>

Ares actively supported his Amazon-queen daughters in their many wars and battles. The most celebrated of these was Penthesileia who joined the Trojan War. <<More>>

When the Aloadai giants laid siege to Olympos, Ares battled them but was defeated and imprisoned in a bronze jar. He was later rescued by the god Hermes. <<More>>

During the course of the Trojan War, Ares, who had sided with the Trojans, was wounded by the Greek hero Diomedes who drove a spear into his side, sending him flying back to Olympos bellowing in pain. <<More>>

Many other minor myths are detailed over the following pages.

SYMBOLS & ATTRIBUTES

Ares’ main attribute was a peaked warrior’s helm. Even in domestic scenes, such as feasts of the gods, he was depicted either wearing or holding his helm. The god’s other attributes included a shield, a spear and sometimes a sheathed sword. Although his shield was often decorated with an emblem of some sort, ancient artists simply used a generic one drawn from their standard repertoire rather than something specific to the god.

Ares was usually dressed as a standard Greek warrior with a short tunic, breastplate, helm and greaves. The breastplate was often ommitted in favour of a simple tunic, and he was sometimes depicted nude except for the helm and shield. Ares can be quite difficult to identify in ancient Greek art as there is little to distinguish him from other warrior figures. <<More>>

SACRED ANIMALS

Ares’ sacred animal was the serpent. He was also associated with certain birds, such as the vulture and a few species of owl, which ancient augury identified as portents of war, sedition and ill-fortune. <<More>>

The most famous of the god’s animals in myth were the Colchian Dragon, a serpent set by Ares to guard the Golden Fleece, and the Ismenian Dragon, a giant snake which guarded his sacred spring near Thebes. <<More>>

ARES PAGES ON THEOI.COM

This site contains a total of 13 pages describing the god, including general descriptions, mythology, and cult. The content is outlined in the Index of Ares Pages list (left column or below).

FAMILY OF ARES

PARENTS

[1.1] ZEUS & HERA (Hesiod Theogony 921, Homer Iliad 5.699, Aeschylus Frag 282, Apollodorus 1.13, Pausanias 2.14.3, Hyginus Preface, et al)

[1.2] HERA (no father) (Ovid Fasti 5.229)

OFFSPRING

See Family of Ares

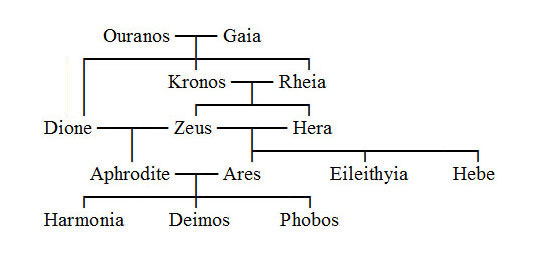

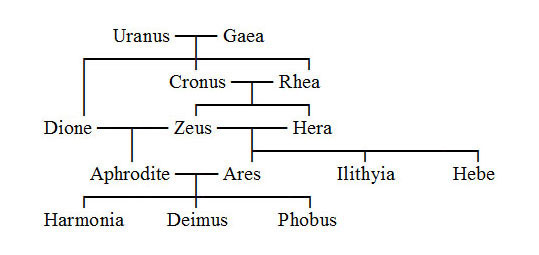

Ares was a son of Zeus and Hera, King and Queen of the Gods, and brother of the goddesses Eileithyia and Hebe. His half-brothers and sisters included Athena, Aphrodite, Apollon, Artemis, Hermes, Dionysos and Hephaistos.

Ares had three children by the goddess Aphrodite named Deimos (Fear), Phobos (Terror), and Harmonia (Harmony). His daughter Harmonia’s daughter Semele was the mother of the god Dionysos.

Ares also had numerous mortal offspring. Many of these inherited their father’s violent temperament and in myth were often cast in the role of villains. <<More>>

Below are two graphics depicting Ares’ family tree, the first with names transliterated from the Greek and the second with the common English spellings:-

ENCYCLOPEDIA

ARES (Arês), the god of war and one of the great Olympian gods of the Greeks. He is represented as the son of Zeus and Hera. (Hom. Il. v. 893, &c.; Hes. Theog. 921; Apollod. i. 3. § 1.) A later tradition, according to which Hera conceived Ares by touching a certain flower, appears to be an imitation of the legend about the birth of Hephaestus, and is related by Ovid. (Fast. v. 255, &c.)

The character of Ares in Greek mythology will be best understood if we compare it with that of other divinities who are likewise in some way connected with war. Athena represents thoughtfulness and wisdom in the affairs of war, and protects men and their habitations during its ravages. Ares, on the other hand, is nothing but the personification of bold force and strength, and not so much the god of war as of its tumult, confusion, and horrors. His sister Eris calls forth war, Zeus directs its course, but Ares loves war for its own sake, and delights in the din and roar of battles, in the slaughter of men, and the destruction of towns. He is not even influenced by party-spirit, but sometimes assists the one and sometimes the other side, just as his inclination may dictate; whence Zeus calls him alloposallos. (Il. v. 889.) The destructive hand of this god was even believed to be active in the ravages made by plagues and epidemics. (Soph. Oed. Tyr. 185.) This savage and sanguinary character of Ares makes him hated by the other gods and his own parents. (Il. v. 889-909.) In the Iliad, he appears surrounded by the personifications of all the fearful phenomena and effects of war (iv. 440, &c., xv. 119, &c.); but in the Odyssey his character is somewhat softened down.

It was contrary to the spirit which animated the Greeks to represent a being like Ares, with all his overwhelming physical strength, as always victorious; and when he comes in contact with higher powers, he is usually conquered. He was wounded by Diomedes, who was assisted by Athena, and in his fall he roared like nine or ten thousand other warriors together. (Il. v. 855, &c.) When the gods began to take an active part in the war of the mortals, Athena opposed Ares, and threw him on the ground by hurling at him a mighty stone (xx. 69, xxi. 403, &c.); and when he lay stretched on the earth, his huge body covered the space of seven plethra.

The gigantic Aloadae had likewise conquered and chained him, and had kept him a prisoner for thirteen months, until he was delivered by Hermes. (v. 385, &c.) In the contest of Typhon against Zeus, Ares was obliged, together with the other gods, to flee to Egypt, where he metamorphosed himself into a fish. (Antonin. Lib. 28.) He was also conquered by Heracles, with whom he fought on account of his son Cycnus, and obliged to return to Olympus. (Hesiod, Scut. Herc. 461.) In numerous other contests, however, he was victorious.

This fierce and gigantic, but withal handsome god loved and was beloved by Aphrodite : he interfered on her behalf with Zeus (v. 883), and lent her his war-chariot. (v. 363; comp. Aphrodite.) When Aphrodite loved Adonis, Ares in his jealonsy metamorphosed himself into a bear, and killed his rival.

According to a late tradition, Ares slew Halirrhotius, the son of Poseidon, when he was on the point of violating Alcippe, the daughter of Ares. Hereupon Poseidon accused Ares in the Areiopagus, where the Olympian gods were assembled in court. Ares was acquitted, and this event was believed to have given rise to the name Areiopagus. (Dict. of Ant. s. v.)

The warlike character of the tribes of Thrace led to the belief, that the god’s residence was in that country, and here and in Scythia were the principal seats of his worship. (Hom. Od. viii. 361, with the note of Eustath.; Ov. Ars Am. ii. 585 ; Statius, Theb. vii. 42; Herod. iv. 59, 62.) In Scythia he was worshipped in the form of a sword, to which not only horses and other cattle, but men also were sacrificed. Respecting the worship of an Egyptian divinity called Ares, see Herodotus, ii. 64.

He was further worshipped in Colchis, where the golden fleece was suspended on an oak-tree in a grove sacred to him. (Apollod. i. 9. § 16.) From thence the Dioscuri were believed to have brought to Laconia the ancient statue of Ares which was preserved in the temple of Ares Thareitas, on the road from Sparta to Therapnae. (Paus. iii. 19. § 7, &c.) The island near the coast of Colchis, in which the Stymphalian birds were believed to have dwelt, and which is called the island of Ares, Aretias, Aria, or Chalceritis, was likewise sacred to him. (Steph. Byz. s. v. Areos nêsos; Apollon. Rhod. ii. 1047; Plin. H. N. vi. 12; Pomp. Mela, ii. 7. § 15.)

In Greece itself the worship of Ares was not very general. At Athens he had a temple containing a statue made by Alcamenes (Paus. i. 8. § 5); at Geronthrae in Laconia he had a temple with a grove, where an annual festival was celebrated, during which no woman was allowed to approach the temple. (iii. 22. § 5.) He was also worshipped near Tegea, and in the town (viii. 44. § 6, 48. § 3), at Olympia (v. 15. § 4), near Thebes (Apollod. iii. 4. § 1), and at Sparta, where there was an ancient statue, representing the god in chains, to indicate that the martial spirit and victory were never to leave the city of Sparta. (Paus. iii. 15. § 5.) At Sparta human sacrifices were offered to Ares. (Apollod. Fragm. p. 1056, ed. Heyne.) The temples of this god were usually built outside the towns, probably to suggest the idea that he was to prevent enemies from approaching them.

All the stories about Ares and his worship in the countries north of Greece seem to indicate that his worship was introduced in the latter country from Thrace; and the whole character of the god, as described by the most ancient poets of Greece, seems to have been thought little suited to be represented in works of art : in fact, we hear of no artistic representation of Ares previous to the time of Alcamenes, who appears to have created the ideal of Ares. There are few Greek monuments now extant with representations of the god; he appears principally on coins, reliefs, and gems. The Romans identified their god Mars with the Greek Ares.

Source: Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

CLASSICAL LITERATURE QUOTES

HYMNS TO ARES

I) THE HOMERIC HYMNS

Homeric Hymn 8 to Ares (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic B.C.) :

“Ares, exceeding in strength, chariot-rider, golden-helmed, doughty in heart, shield-bearer, Saviour of cities, harnessed in bronze, strong of arm, unwearying, mighty with the spear, O defender of Olympos, father of warlike Nike (Victory), ally of Themis, stern governor of the rebellious, leader of the righteous men, sceptred King of manliness, who whirl your fiery sphere [the star Mars] among the planets in their sevenfold courses through the aither wherein your blazing steeds ever bear you above the third firmament of heaven; hear me, helper of men, giver of dauntless youth! Shed down a kindly ray from above upon my life, and strength of war, that I may be able to drive away bitter cowardice from my head and crush down the deceitful impulses of my soul. Restrain also the keen fury of my heart which provokes me to tread the ways of blood-curdling strife. Rather, O blessed one, give you me boldness to abide within the harmless laws of peace, avoiding strife and hatred and the violent fiends of death.”

II) THE ORPHIC HYMNS

Orphic Hymn 65 to Ares (trans. Taylor) (Greek hymns C3rd B.C. to 2nd A.D.) :

“To Ares, Fumigation from Frankincense. Magnanimous, unconquered, boisterous Ares, in darts rejoicing, and in bloody wars; fierce and untamed, whose mighty power can make the strongest walls from their foundations shake: mortal-destroying king, defiled with gore, pleased with war’s dreadful and tumultuous roar. Thee human blood, and swords, and spears delight, and the dire ruin of mad savage fight. Stay furious contests, and avenging strife, whose works with woe embitter human life; to lovely Kypris (Cypris) [Aphrodite] and to Lyaios (Lyaeus) [Dionysos] yield, for arms exchange the labours of the field; encourage peace, to gentle works inclined, and give abundance, with benignant mind.”

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTIONS OF ARES

Classical literature offers only a few, brief descriptions of the physical characteristics of the gods.

Homer, Iliad 5. 592 ff (trans. Lattimore) (Greek epic C8th B.C.) :

“Ares made play in his hands with spear gigantic and ranged now in front of Hektor and now behind him. Diomedes of the great war cry shivered [with fear] as he saw him.”

Homer, Iliad 18. 516 ff :

“[In a battle-scene engraved on the shield of Akhilleus (Achilles):] And Ares led them [an army of men], and Pallas Athene. These were gold, both, and golden raiment upon them, and they were beautiful and huge in their armour, being divinities, and conspicuous from afar, but the people around them were smaller.”

Hesiod, Shield of Heracles 56 ff (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic C8th or 7th B.C.) :

“Ares insatiable in battle, blazing like the light of burning fire in his armour and standing in his chariots, and his running horses trampled and dented the ground with their hooves . . . And all the grove and the altar . . . were lighted up by the dread god, Ares, himself and his armour, and the shining from his eyes was like fire . . . manslaughtering Ares screaming aloud, courses all over the sacred grove.”

Hesiod, Shield of Heracles 191 ff :

“[In a battle-scene engraved on the shield of Herakles:] And on the shield stood the fleet-footed horses of grim Ares made gold, and deadly Ares the spoil-winner himself. He held a spear in his hands and was urging on the footmen: he was red with blood as if he were slaying living men, and he stood in his chariot. Beside him stood Deimos (Fear) and Phobos (Flight), eager to plunge amidst the fighting men.”

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 1. 923 ff (trans. Way) (Greek epic C4th A.D.) :

“Straight from Olympus down he [Ares] darted, swift and bright as thunderbolt terribly flashing from the mighty hand of Zeus.”

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 7. 400 ff :

“Ares, to gory strife he speedeth, wroth with foes, when maddeneth his heart, and grim his frown is, and his eyes flash levin-flame around him, and his face is clothed with glory of beauty terror-blent, as on he rusheth: quail the very gods.”

ANCIENT GREEK & ROMAN ART

SOURCES (ALL ARES PAGES)

GREEK

- Homer, The Iliad – Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Homer, The Odyssey – Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Hesiod, Theogony – Greek Epic C8th – 7th B.C.

- Hesiod, The Shield of Heracles – Greek Epic C8th – 7th B.C.

- Hesiod, Catalogues of Women Fragments – Greek Epic C8th – 7th B.C.

- The Homeric Hymns – Greek Epic C8th – 4th B.C.

- Epic Cycle, The Aethiopis Fragments – Greek Epic C8th B.C.

- Epic Cycle, The Telegony Fragments – Greek Epic C8th – 6th B.C.

- Greek Lyric II Anacreontea, Fragments – Greek Lyric C5th – 4th B.C.

- Greek Lyric III Stesichorus, Fragments – Greek Lyric C7th – 6th B.C.

- Greek Lyric III Ibycus, Fragments – Greek Lyric C6th B.C.

- Greek Lyric III Simonides, Fragments – Greek Lyric C6th – 5th B.C.

- Greek Lyric IV Corinna, Fragments – Greek Lyric C5th B.C.

- Greek Elegaic Mimnermus, Fragments – Greek Elegaic C7th B.C.

- Greek Elegaic Theognis, Fragments – Greek Elegaic C6th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Agamemnon – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Eumenides – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Libation Bearers – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Suppliant Women – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Aeschylus, Fragments – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Euripides, Bacchae – Greek Tragedy C5th B.C.

- Herodotus, Histories – Greek History C5th B.C.

- Plato, Cratylus – Greek Philosophy C4th B.C.

- Plato, Laws – Greek Philosophy C4th B.C.

- Plato, Republic – Greek Philosophy C4th B.C.

- Apollodorus, The Library – Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Apollonius Rhodius, The Argonautica – Greek Epic C3rd B.C.

- Callimachus, Hymns – Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

- Callimachus, Fragments – Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

- Greek Papyri III Euphorion, Fragments – Greek Epic C3rd B.C.

- Greek Papyri III Amyntas, Fragments – Greek Elegiac C2nd B.C.

- Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History – Greek History C1st B.C.

- Strabo, Geography – Greek Geography C1st B.C. – C1st A.D.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece – Greek Travelogue C2nd A.D.

- Plutarch, Moralia – Greek Historian C1st – 2nd A.D.

- Plutarch, Parallel Stories – Greek Historian C1st – 2nd A.D.

- The Orphic Hymns – Greek Hymns C3rd B.C. – C2nd A.D.

- Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses – Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Aelian, Historical Miscellany – Greek Rhetoric C2nd – 3rd A.D.

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae – Greek Rhetoric C3rd A.D.

- Philostratus the Younger, Imagines – Greek Rhetoric C3rd A.D.

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana – Greek Biography C2nd A.D.

- Oppian, Halieutica – Greek Poetry C3rd A.D.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy – Greek Epic C4th A.D.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca – Greek Epic C5th A.D.

- Colluthus, The Rape of Helen – Greek Epic C5th – 6th A.D.

- Greek Papyri III Anonymous, Fragments – Greek Poetry C4th A.D.

ROMAN

- Hyginus, Fabulae – Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Hyginus, Astronomica – Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses – Latin Epic C1st B.C. – C1st A.D.

- Ovid, Fasti – Latin Poetry C1st B.C. – C1st A.D.

- Ovid, Heroides – Latin Poetry C1st B.C. – C1st A.D.

- Virgil, Aeneid – Latin Epic C1st B.C.

- Virgil, Georgics – Latin Bucolic C1st B.C.

- Cicero, De Natura Deorum – Latin Rhetoric C1st B.C.

- Seneca, Hercules Furens – Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Medea – Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Phaedra – Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Seneca, Troades – Latin Tragedy C1st A.D.

- Valerius Flaccus, The Argonautica – Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Statius, Thebaid – Latin Epic C1st A.D.

- Statius, Silvae – Latin Poetry C1st A.D.

- Apuleius, The Golden Ass – Latin Novel C2nd A.D.

BYZANTINE

- Suidas, The Suda – Byzantine Greek Lexicon C10th A.D.

OTHER SOURCES

Source status of Ares pages:-

1. Fully quoted: Homer (Iliad & Odyssey), Hesiod, Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle & Homerica, Apollodorus, Pausanias, Strabo, Herodotus, Orphic Hymns, Quintus Smyrnaeus, Callimachus, Aesop, Aelian,Ovid (Metamorphoses), Hyginus (Fabulae & Astronomica), Apuleius;

2. Partially or not quoted (Greek): Pindar, Greek Lyric (Fragments), Greek Elegaic (Fragments), Apollonius Rhodius, Diodorus Siculus, Antoninus Liberalis, Euripides, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes, Plato, Theocritus, Lycophron, Plutarch, Philostratus & Callistratus, Nonnus;, Oppian, Tryphiodorus, et. al.;

3. Partially or not quoted (Latin): Ovid (Fasti), Cicero, Statius, Colluthus, Propertius, Valerius Flaccus, et. al.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A complete bibliography of the translations quoted on this page.

Ares

| Ares | |

|---|---|

| God of war | |

Statue of Ares from Hadrian’s Villa

|

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus, Thrace, Macedonia, Thebes, Sparta & Mani |

| Symbols | Sword, spear, shield, helmet, chariot, flaming torch, dog, boar, vulture |

| Personal Information | |

| Consort | Aphrodite and various others |

| Children | Erotes (Eros and Anteros), Phobos, Deimos, Phlegyas, Harmonia, Enyalios, Thrax, Oenomaus, Amazons and Adrestia |

| Parents | Zeus and Hera |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Roman equivalent | Mars |

| This article contains special characters.Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols. |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

|

Features[show]

|

|

Godheads[show]

|

|

Ethics[show]

|

|

Practices[show]

|

|

Sacred places[show]

|

|

Texts[show]

|

|

History[show]

|

Ares (/ˈɛəriːz/; Greek: Ἄρης [árɛːs]) is the Greek god of war. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera.[1] In Greek literature, he often represents the physical or violent and untamed aspect of war, in contrast to his sister the armored Athena, whose functions as a goddess of intelligence include military strategy and generalship.[2]

The Greeks were ambivalent toward Ares: although he embodied the physical valor necessary for success in war, he was a dangerous force, “overwhelming, insatiable in battle, destructive, and man-slaughtering.”[3] His sons Phobos(Fear) and Deimos (Terror) and his lover, or sister, Enyo (Discord) accompanied him on his war chariot.[4] In the Iliad, his father Zeus tells him that he is the god most hateful to him.[5] An association with Ares endows places and objects with a savage, dangerous, or militarized quality.[6] His value as a war god is placed in doubt: during the Trojan War, Ares was on the losing side, while Athena, often depicted in Greek art as holding Nike (Victory) in her hand, favoured the triumphant Greeks.[3]

Ares plays a relatively limited role in Greek mythology as represented in literary narratives, though his numerous love affairs and abundant offspring are often alluded to.[7] When Ares does appear in myths, he typically faces humiliation.[8] He is well known as the lover of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, who was married to Hephaestus, god of craftsmanship.[9] The most famous story related to Ares and Aphrodite shows them exposed to ridicule through the wronged husband’s device.[10]

The counterpart of Ares among the Roman gods is Mars,[11] who as a father of the Roman people was given a more important and dignified place in ancient Roman religion as a guardian deity. During the Hellenization of Latin literature, the myths of Ares were reinterpreted by Roman writers under the name of Mars. Greek writers under Roman rule also recorded cult practices and beliefs pertaining to Mars under the name of Ares. Thus in the classical tradition of later Western art and literature, the mythology of the two figures becomes virtually indistinguishable.

Contents

[hide]

Names[edit]

The etymology of the name Ares is traditionally connected with the Greek word ἀρή (arē), the Ionic form of the Doric ἀρά (ara), “bane, ruin, curse, imprecation”.[12][13] There may also be a connection with the Roman god of war, Mars, via hypothetical Proto-Indo-European *M̥rēs;[citation needed] compare Ancient Greek μάρναμαι (marnamai), “I fight, I battle”.[14] Walter Burkert notes that “Ares is apparently an ancient abstract noun meaning throng of battle, war.”[15] R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name.[16]

The earliest attested form of the name is the Mycenaean Greek ??, a-re, written in the Linear B syllabic script.[17][18][19]

The adjectival epithet, Areios, was frequently appended to the names of other gods when they took on a warrior aspect or became involved in warfare: Zeus Areios, Athena Areia, even Aphrodite Areia. In the Iliad, the word ares is used as a common noun synonymous with “battle.”[3]

Inscriptions as early as Mycenaean times, and continuing into the Classical period, attest to Enyalios as another name for the god of war.[n 1]

Character, origins, and worship[edit]

Vatican, Rome, Italy. Statue of Ares, Scopas‘s influence. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

Ares was one of the Twelve Olympians in the archaic tradition represented by the Iliad and Odyssey. Zeus expresses a recurring Greek revulsion toward the god when Ares returns wounded and complaining from the battlefield at Troy:

Then looking at him darkly Zeus who gathers the clouds spoke to him:

“Do not sit beside me and whine, you double-faced liar.

To me you are the most hateful of all gods who hold Olympus.

Forever quarrelling is dear to your heart, wars and battles.

…

And yet I will not long endure to see you in pain, since

you are my child, and it was to me that your mother bore you.

But were you born of some other god and proved so ruinous

long since you would have been dropped beneath the gods of the bright sky.”[22]

This ambivalence is expressed also in the Greeks’ association of the god with the Thracians, whom they regarded as a barbarous and warlike people.[23] Thrace was Ares’s birthplace, his true home, and his refuge after the affair with Aphrodite was exposed to the general mockery of the other gods.[n 2]

A late-6th-century BC funerary inscription from Attica emphasizes the consequences of coming under Ares’s sway:

Stay and mourn at the tomb of dead Kroisos

Whom raging Ares destroyed one day, fighting in the foremost ranks.[24]

Ares in Sparta[edit]

In Sparta, Ares was viewed as a model soldier: his resilience, physical strength, and military intelligence were unrivaled. An ancient statue, representing the god in chains, suggests that the martial spirit and victory were to be kept in the city of Sparta. That the Spartans admired him is indicative of the cultural divisions that existed between themselves and other Greeks, especially the Athenians (see Pelopponesian War).

Ares in the Arabian Peninsula[edit]

Ares was also worshipped by the inhabitants of Tylos. It is not known if he was worshipped in the form of an Arabian god (or which one) or if he was worshipped in his Greek form.[25]

Attributes[edit]

The Ares Borghese.

The birds of Ares (Ornithes Areioi) were a flock of feather-dart-dropping birds that guarded the Amazons‘ shrine of the god on a coastal island in the Black Sea.[26]

Cult and ritual[edit]

Although Ares received occasional sacrifice from armies going to war, the god had a formal temple and cult at only a few sites.[27] At Sparta, however, each company of youths sacrificed a puppy to Enyalios before engaging in ritual fighting at the Phoebaeum.[n 3] The chthonic night-time sacrifice of a dog to Enyalios became assimilated to the cult of Ares.[29]

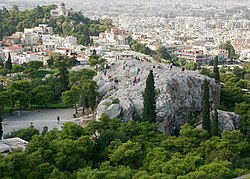

Just east of Sparta stood an archaic statue of the god in chains, to show that the spirit of war and victory was to be kept in the city.[n 4]

The Temple of Ares in the agora of Athens, which Pausanias saw in the second century AD, had been moved and rededicated there during the time of Augustus. Essentially it was a Roman temple to the Augustan Mars Ultor.[27] From archaic times, the Areopagus, the “mount of Ares” at some distance from the Acropolis, was a site of trials. Paul the Apostle later preached about Christianity there. Its connection with Ares, perhaps based on a false etymology, is etiological myth.[citation needed] A second temple to Ares has been located at the archaeological site of Metropolis in what is now Western Turkey.[citation needed]

Attendants[edit]

Deimos, “Terror” or “Dread”, and Phobos, “Fear” or “Horror”, are his companions in war.[31] According to Hesiod, they were also his children, borne by Aphrodite.[32] Eris, the goddess of discord, or Enyo, the goddess of war, bloodshed, and violence, was considered the sister[citation needed] and companion of the violent Ares. In at least one tradition, Enyalius, rather than another name for Ares, was his son by Enyo.[33]

Ares may also be accompanied by Kydoimos, the demon of the din of battle; the Makhai (“Battles”); the “Hysminai” (“Acts of manslaughter”); Polemos, a minor spirit of war, or only an epithet of Ares, since it has no specific dominion; and Polemos’s daughter, Alala, the goddess or personification of the Greek war-cry, whose name Ares uses as his own war-cry. Ares’s sister Hebe (“Youth”) also draws baths for him.

According to Pausanias, local inhabitants of Therapne, Sparta, recognized Thero, “feral, savage,” as a nurse of Ares.[34]

Founding of Thebes[edit]

One of the roles of Ares was expressed in mainland Greece as the founding myth of Thebes: Ares was the progenitor of the water-dragon slain by Cadmus, for the dragon’s teeth were sown into the ground as if a crop and sprang up as the fully armored autochthonic Spartoi. To propitiate Ares, Cadmus took as a bride Harmonia, a daughter of Ares’s union with Aphrodite. In this way, Cadmus harmonized all strife and founded the city of Thebes.[35]

Consorts and children[edit]

The union of Ares and Aphrodite created the gods Eros, Anteros, Phobos, Deimos, Harmonia, and Adrestia. While Eros’s and Anteros’s godly stations favored their mother, Adrestia preferred to emulate her father, often accompanying him to war.[citation needed] Other versions include Alcippe as one of his daughters.

Upon one occasion, Ares incurred the anger of Poseidon by slaying his son, Halirrhothius, because he had raped Alcippe, a daughter of the war-god. For this deed, Poseidon summoned Ares to appear before the tribunal of the Olympic gods, which was held upon a hill in Athens. Ares was acquitted. This event is supposed to have given rise to the name Areopagus (or Hill of Ares), which afterward became famous as the site of a court of justice.[36]

Accounts tell of Cycnus (Κύκνος) of Macedonia, a son of Ares who was so murderous that he tried to build a temple with the skulls and the bones of travellers. Heracles slaughtered this abominable monstrosity, engendering the wrath of Ares, whom the hero wounded in conflict.[37]

List of Ares’s consorts and children[edit]

| Consorts | Children |

|---|---|

| 1. Aphrodite | 1. Phobos |

| 2. Deimos | |

| 3. Harmonia | |

| 4. Adrestia | |

| 5. Eros (part of the Erotes) | |

| 6. Anteros (part of the Erotes) | |

| 7. Himeros (part of the Erotes) | |

| 8. Pothos (part of the Erotes) | |

| 2. Aerope | 1. Aeropus |

| 3. Aglauros | 1. Alcippe |

| 4. Althaea | 1. Meleager (possibly) |

| 5. Anchiroe | 1. Sithon (possibly) |

| 6. Astyoche, daughter of Actor | 1. Ascalaphus |

| 2. Ialmenus | |

| 7. Atalanta | 1. Parthenopaeus (possibly) |

| 8. Caldene, daughter of Pisidus | 1. Solymus (possibly) |

| 9. Calliope (Muse) | 1.Mygdon |

| 2. Edonus (possibly) | |

| 3. Biston (possibly) | |

| 4. Odomantus (possibly) | |

| 10. Callirrhoe, daughter of Nestus | 1. Biston (possibly) |

| 2. Odomantus (possibly) | |

| 3. Edonus (possibly) | |

| 11. Critobule | 1. Pangaeus[38] |

| 12. Cyrene[39] | 1. Diomedes of Thrace |

| 2. Crestone[40] | |

| 13. Demonice | 1. Euenus |

| 2. Thestius | |

| 3. Molus | |

| 4. Pylus | |

| 14. Dormothea | 1. Stymphelus[41] |

| 15. Dotis / Chryse | 1. Phlegyas |

| 16. Enyo | 1. Enyalius |

| 17. Eos | |

| 18. Erinys of Telphusa (unnamed) | 1. Dragon of Thebes (slain by Cadmus) |

| 19. Harmonia | 1. The Amazons |

| 20. Leodoce (?)[42] | |

| 21. Otrera | 1. Hippolyta |

| 2. Antiope | |

| 3. Melanippe | |

| 4. Penthesilea | |

| 22. Parnassa / Aegina | 1. Sinope (possibly)[43] |

| 23. Phylonome | 1. Lycastus |

| 2. Parrhasius | |

| 24. Protogeneia | 1. Oxylus |

| 25. Pyrene / Pelopia | 1. Cycnus |

| 26. Sete, sister of Rhesus | 1. Bithys, eponym of the Bithyae, a Thracian tribe[44] |

| 27. Sterope (Pleiad) / Harpinna, daughter of Asopus / Eurythoe the Danaid | 1. Oenomaus |

| 28. Persephone (wooed her unsuccessfully) | |

| 29. Tanagra, daughter of Asopus | |

| 30. Tereine, daughter of Strymon | 1. Thrassa (mother of Polyphonte) |

| 31. Theogone | 1. Tmolus[45] |

| 32. Triteia | 1. Melanippus |

| 33. mothers unknown | 1. Alcon of Thrace[46] |

| 2. Chalyps, eponym of the Chalybes[47] | |

| 3. Cheimarrhoos, possible father of Triptolemus by Polyhymnia[48] | |

| 4. Dryas | |

| 5. Hyperbius | |

| 6. Lycus of Libya[49] | |

| 7. Nisos (possibly) | |

| 8. Portheus (Porthaon) | |

| 9. Tereus |

Hymns to Ares[edit]

- Homeric Hymn 8 to Ares (trans. Evelyn-White) (Greek epic 7th to 4th centuries BC)

- “Ares, exceeding in strength, chariot-rider, golden-helmed, doughty in heart, shield-bearer, Saviour of cities, harnessed in bronze, strong of arm, unwearying, mighty with the spear, O defence of Olympus, father of warlike Victory, ally of Themis, stern governor of the rebellious, leader of righteous men, sceptred King of manliness, who whirl your fiery sphere among the planets in their sevenfold courses through the aether wherein your blazing steeds ever bear you above the third firmament of heaven; hear me, helper of men, giver of dauntless youth! Shed down a kindly ray from above upon my life, and strength of war, that I may be able to drive away bitter cowardice from my head and crush down the deceitful impulses of my soul. Restrain also the keen fury of my heart which provokes me to tread the ways of blood-curdling strife. Rather, O blessed one, give you me boldness to abide within the harmless laws of peace, avoiding strife and hatred and the violent fiends of death.”[50]

- Orphic Hymn 65 to Ares (trans. Taylor) (Greek hymns 3rd century BC to 2nd century AD)

- “To Ares, Fumigation from Frankincense. Magnanimous, unconquered, boisterous Ares, in darts rejoicing, and in bloody wars; fierce and untamed, whose mighty power can make the strongest walls from their foundations shake: mortal-destroying king, defiled with gore, pleased with war’s dreadful and tumultuous roar. Thee human blood, and swords, and spears delight, and the dire ruin of mad savage fight. Stay furious contests, and avenging strife, whose works with woe embitter human life; to lovely Kyrpis [Aphrodite] and to Lyaios [Dionysos] yield, for arms exchange the labours of the field; encourage peace, to gentle works inclined, and give abundance, with benignant mind.”

Other accounts[edit]

The Ludovisi Ares, Roman version of a Greek original c. 320 BC, with 17th-century restorations by Bernini

Ares and Aphrodite[edit]

In the tale sung by the bard in the hall of Alcinous,[51] the Sun-god Helios once spied Ares and Aphrodite enjoying each other secretly in the hall of Hephaestus, her husband. He reported the incident to Hephaestus. Contriving to catch the illicit couple in the act, Hephaestus fashioned a finely-knitted and nearly invisible net with which to snare them. At the appropriate time, this net was sprung, and trapped Ares and Aphrodite locked in very private embrace.[n 5]

But Hephaestus was not satisfied with his revenge, so he invited the Olympian gods and goddesses to view the unfortunate pair. For the sake of modesty, the goddesses demurred, but the male gods went to witness the sight. Some commented on the beauty of Aphrodite, others remarked that they would eagerly trade places with Ares, but all who were present mocked the two. Once the couple was released, the embarrassed Ares returned to his homeland, Thrace, and Aphrodite went to Paphos.[n 5]

In a much later interpolated detail, Ares put the young soldier Alectryon by his door to warn them of Helios’s arrival as Helios would tell Hephaestus of Aphrodite’s infidelity if the two were discovered, but Alectryon fell asleep on guard duty.[citation needed] Helios discovered the two and alerted Hephaestus. The furious Ares turned the sleepy Alectryon into a rooster which now always announces the arrival of the sun in the morning.

Ares and the giants[edit]

In one archaic myth, related only in the Iliad by the goddess Dione to her daughter Aphrodite, two chthonic giants, the Aloadae, named Otus and Ephialtes, threw Ares into chains and put him in a bronze urn, where he remained for thirteen months, a lunar year. “And that would have been the end of Ares and his appetite for war, if the beautiful Eriboea, the young giants’ stepmother, had not told Hermes what they had done,” she related.[52] “In this one suspects a festival of licence which is unleashed in the thirteenth month.”[53]

Ares was held screaming and howling in the urn until Hermes rescued him, and Artemis tricked the Aloadae into slaying each other. In Nonnus‘s Dionysiaca[54] Ares also killed Ekhidnades, the giant son of Echidna, and a great enemy of the gods. Scholars have not concluded whether the nameless Ekhidnades (“of Echidna’s lineage”) was entirely Nonnus’s invention or not.

Iliad[edit]

In the Iliad,[55] Homer represented Ares as having no fixed allegiances, rewarding courage on both sides: he promised Athena and Hera that he would fight on the side of the Achaeans (Iliad V.830–834, XXI.410–414), but Aphroditepersuaded Ares to side with the Trojans. During the war, Diomedes fought with Hector and saw Ares fighting on the Trojans’ side. Diomedes called for his soldiers to fall back slowly (V.590–605).

Athene or Athena, Ares’s sister, saw his interference and asked Zeus, his father, for permission to drive Ares away from the battlefield, which Zeus granted (V.711–769). Hera and Athena encouraged Diomedes to attack Ares (V.780–834). Diomedes thrust with his spear at Ares, with Athena driving it home, and Ares’s cries made Achaeans and Trojans alike tremble (V.855–864). Ares fled to Mt. Olympus, forcing the Trojans to fall back.

When Hera mentioned to Zeus that Ares’s son, Ascalaphus, was killed, Ares overheard and wanted to join the fight on the side of the Achaeans, disregarding Zeus’s order that no Olympic god should enter the battle, but Athena stopped him (XV.110–128). Later, when Zeus allowed the gods to fight in the war again (XX.20–29), Ares was the first to act, attacking Athena to avenge himself for his previous injury. Athena overpowered him by striking Ares with a boulder (XXI.391–408).

Renaissance[edit]

In Renaissance and Neoclassical works of art, Ares’s symbols are a spear and helmet, his animal is a dog, and his bird is the vulture. In literary works of these eras, Ares is replaced by the Roman Mars, a romantic emblem of manly valor rather than the cruel and blood-thirsty god of Greek mythology.

In popular culture[edit]

Ares figures in war-themed video games and in popular fictions.

NASA named their transport ship as Ares, which replaced the Space Shuttle. This was an extension of NASA’s practice of using Roman and Greek names for their rockets and programs: Saturn for manned rockets, Mercury for a satellite program, and the Apollo program, rather than any association with the nature of the war god.

See also[edit]

- Related Greek deities

- Children by Aphrodite

- Harmonia (Concord)

- Eros (Passionate love)

- Phobos (Fear)

- Deimos (Terror)

- Adrestia (Revenge)

- Anteros (Requited love)

- Friends and counselors

- Attendants

- Achlys (Death)

- Androktasiai (Slaughter)

- Alala (War cry)

- Eris (Strife)

- Enyo (Violence)

- Hebe (Life)

- Homados (Battle din)

- Hysminai (Combat)

- Kydoimos (Confusion)

- Keres (Death spirits)

- Makhai (Spirits of battle)

- Palioxis (Backrush)

- Polemos (War)

- Proioxis (Onrush)

- Similar deities in non-Greek cultures

- Britannia

- Kathleen Ni Houlihan

- Liberty

- Mars

- Nergal, Babylonian god associated with the planet Mars

- Tyr, a Norse god of war

- List of war deities

- Archetypical characteristics

Notes and references[edit]

- Notes

- Jump up^ Enyalios is thought to be attested on the KN V 52 tablet as ?????, e-nu-wa-ri-jo.[20][21]

- Jump up^ Homer Odyssey viii. 361; for Ares/Mars and Thrace, see Ovid, Ars Amatoria, book ii.part xi.585, which tells the same tale: “Their captive bodies are, with difficulty, freed, at your plea, Neptune: Venus runs to Paphos: Mars heads for Thrace.”; for Ares/Mars and Thrace, see also Statius, Thebaid vii. 42; Herodotus, iv. 59, 62.

- Jump up^ “Here each company of youths sacrifices a puppy to Enyalius, holding that the most valiant of tame animals is an acceptable victim to the most valiant of the gods. I know of no other Greeks who are accustomed to sacrifice puppies except the people of Colophon; these too sacrifice a puppy, a black bitch, to the Wayside Goddess”.[28]

- Jump up^ “Opposite this temple [the temple of Hipposthenes] is an old image of Enyalius in fetters. The idea the Lacedaemonians express by this image is the same as the Athenians express by their Wingless Victory; the former think that Enyalius will never run away from them, being bound in the fetters, while the Athenians think that Victory, having no wings, will always remain where she is”.[30]

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Odyssey, 8.295”.

[In Robert Fagles‘s translation]: … and the two lovers, free of the bonds that overwhelmed them so, sprang up and away at once, and the Wargod sped Thrace, while Love with her telltale laughter sped to Paphos …

- References

- Jump up^ Hesiod, Theogony 921 (Loeb Classical Library numbering); Iliad, 5.890–896. By contrast, Ares’s Roman counterpart Mars was born from Juno alone, according to Ovid (Fasti 5.229–260).

- Jump up^ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Blackwell, 1985, 2004 reprint, originally published 1977 in German), pp. 141; William Hansen, Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 113.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 169.

- Jump up^ Burkert, Greek Religion, p.169.

- Jump up^ Iliad 5.890–891.

- Jump up^ Hansen, Classical Mythology, pp. 114–115.

- Jump up^ Hansen, Classical Mythology, pp. 113–114; Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 169.

- Jump up^ Hansen, Classical Mythology, pp. 113–114. See for instance Ares and the giants below.

- Jump up^ In the Iliad, however, the wife of Hephaestus is Charis, “Grace,” as noted by Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 168.

- Jump up^ Odyssey 8.266–366; Hansen, Classical Mythology, pp. 113–114.

- Jump up^ Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia, The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215.

- Jump up^ Harper, Douglas. “Ares”. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Jump up^ ἀρή, Georg Autenrieth, A Homeric Dictionary. ἀρή. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Jump up^ μάρναμαι in Liddell and Scott.

- Jump up^ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Harvard) 1985:pt III.2.12 p. 169.

- Jump up^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, pp. 129–130.

- Jump up^ Gulizio, Joannn. “A-re in the Linear B Tablets and the Continuity of the Cult of Ares in the Historical Period” (PDF). Journal of Prehistoric Religion. 15: 32–38.

- Jump up^ Raymoure, K.A. (2012). “a-re”. Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean.

- Jump up^ “The Linear B word a-re”. Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages.

- Jump up^ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-521-29037-6. At Google Books.

- Jump up^ Raymoure, K.A. “e-nu-wa-ri-jo”. Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. “KN 52 V + 52 bis + 8285 (unknown)”. DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo. Archived from the original on 2014-03-19.

- Jump up^ Iliad, Book 5, lines 798–891, 895–898 in the translation of Richmond Lattimore.

- Jump up^ Iliad 13.301; Ovid, Ars Amatoria, II.10.

- Jump up^ Athens, NM 3851 quoted in Andrew Stewart, One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works, Introduction: I. “The Sources”

- Jump up^ الاحتلال المقدوني للبحرين ص ١٢٨

- Jump up^ Argonautica (ii.382ff and 1031ff; Hyginus, Fabulae 30.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 170.

- Jump up^ Pausanias, 3.14.9.

- Jump up^ “Ares”. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/9344. Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- Jump up^ Pausanias, 3.15.7.

- Jump up^ Iliad 4.436f, and 13.299f’ Hesiodic Shield of Heracles 191, 460; Quintus Smyrnaeus, 10.51, etc.

- Jump up^ Hesiod, Theogony 934f.

- Jump up^ Eustathius on Homer, 944

- Jump up^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 3. 19. 7 – 8

- Jump up^ Burkert, Greek Religion, p.169.

- Jump up^ Berens, E.M.: Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome, page 113. Project Gutenberg, 2007.

- Jump up^ Bibliotheca 2. 5. 11 & 2. 7. 7

- Jump up^ Pseudo-Plutarch, On Rivers, 3. 2

- Jump up^ Bibliotheca 2. 5. 8

- Jump up^ Tzetzes on Lycophron, 499: Thrace was said to have been called Crestone after her.

- Jump up^ Pseudo-Plutarch, On Rivers, 19. 1

- Jump up^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 159

- Jump up^ Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, 2. 946

- Jump up^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s. v. Bithyai

- Jump up^ Pseudo-Plutarch, On Rivers, 7. 5

- Jump up^ Hyginus, Fabulae, 173

- Jump up^ Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, 2. 373

- Jump up^ Scholia on Hesiod, Works and Days, 1, p. 28

- Jump up^ Pseudo-Plutarch, Greek and Roman Parallel Stories, 23

- Jump up^ Homeric Hymn to Ares.

- Jump up^ Odyssey 8.300

- Jump up^ Iliad 5.385–391.

- Jump up^ Burkert (1985). Greek Religion. p. 169.

- Jump up^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 18. 274 ff; Theoi.com, “Ekhidnades”.

- Jump up^ References to Ares’s appearance in the Iliad are collected and quoted at www.theoi.com: Ares Myths 2

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ares. |

| Look up Ares in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Theoi Project, Ares—information on Ares from classical literature, Greek and Roman art.

- Facebook Archetype Page Image Gallery and Popular Contemporary Mentions

Navigation menu

Interaction

Tools

Print/export

In other projects

Languages

- Afrikaans

- Alemannisch

- العربية

- Aragonés

- Azərbaycanca

- تۆرکجه

- বাংলা

- Bân-lâm-gú

- Беларуская

- Беларуская (тарашкевіца)

- Български

- Boarisch

- Bosanski

- Brezhoneg

- Català

- Čeština

- Cymraeg

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Eesti

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Gaeilge

- Galego

- 한국어

- Հայերեն

- हिन्दी

- Hrvatski

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Interlingua

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- Basa Jawa

- ქართული

- Қазақша

- Kiswahili

- Кыргызча

- Latina

- Latviešu

- Lëtzebuergesch

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Македонски

- മലയാളം

- मराठी

- مصرى

- Bahasa Melayu

- မြန်မာဘာသာ

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk

- Norsk nynorsk

- Occitan

- ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

- Plattdüütsch

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Русский

- Scots

- Shqip

- සිංහල

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Tagalog

- தமிழ்

- Татарча/tatarça

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- Vepsän kel’

- Tiếng Việt

- West-Vlams

- Winaray

- 粵語

- Zazaki

- 中文

- This page was last edited on 14 November 2017, at 15:47.

- Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

- Privacy policy

- About Wikipedia

- Disclaimers

- Contact Wikipedia

- Developers

- Cookie statement

- Mobile view

- Enable previews