Perhaps that’s because Christmas is a holiday largely based on what most would call pagan festivals. In fact, it’s likely that Christians appropriated an ancient, cross-cultural tradition for our Christmas celebration that predates Christ by centuries, if not millennia.

Christ was not born in December. We learn from modern revelation that he was actually born in April. (See Doctrine and Covenants, Section 20.)

The idea to celebrate Christmas on December 25 originated in about the 4th century. The Catholic Church, based in Rome, wanted to eclipse the festivities of the original pagan religion of the Romans called Saturnalia. It was their preeminent holiday, a midwinter celebration of the birthday of their sun god, Saturnus. Church leaders decided that in order to alter pagan beliefs, they had only to superimpose the birth of the Christ child on the pagan celebration. So, they instituted the Mass of Christ or Cristes Maesse in Old English — Christmas.

In fact, there are an abundance of pagan midwinter festivals from cultures and religions the world over.

Special sanctity was attached to the period of the winter solstice in most traditional societies of Europe even before the introduction of Christianity in the first millennium A.D. The cult of the tree was especially prevalent among the early Celtic and Nordic peoples of Europe. Centuries ago in Great Britain, the Druids used holly and mistletoe as well as evergreens as symbols of eternal life during mysterious winter solstice rituals. They would also place evergreen branches over doors to keep away evil spirits. According to the Roman sources, the Celts of Gaul and Britain worshipped in groves of trees. When Europeans adopted Christian traditions, they created a blend of their winter solstice celebrations with that of the Catholic Church.

So, the roots of Christmas and its symbolic trappings lie deep in pagan cultural traditions, practices and beliefs, not in Christianity at all. This admixture of traditions — part Christian, part pagan — has created the hodgepodge holiday we know today.

For those reasons, many Latter-day Saints disapprove of the “worldly” trappings of Christmas. But that distaste may not be justified.

In an astonishing irony, a close look shows us that the iconography of latter-day temples — the Salt Lake Temple being the quintessential example — echoes the traditional, symbolic trappings from hoary antiquity that are now part of our Christmas celebration, validating symbols like Santa Claus and the Christmas tree.

The basis for this claim becomes clear when we look for indications of our Christmas traditions in numerous ancient cultures and then connect them with the symbolism found on the exterior walls of the temple in Salt Lake City.

So, let’s review the origins and history of today’s Christmas.

The controversial Gerald Massey, in two large works (The Natural Genesis and Ancient Egypt), claimed that the priest-astronomers of ancient Egypt first formulated the religion and mythology of a polar god, which tradition then spread from Egypt to the rest of the world. This may have been the starting point for our Santa Claus, a magical individual who lives at the North Pole. Additionally, ancient Egyptians treasured and worshipped evergreens. When the winter solstice arrived, they brought green date palm leaves into their homes to symbolize life's triumph over death.

Later, the Greeks memorialized the winter solstice with Kronia, a festival recalling the Golden Age, ruled by Kronos, another polar god and the father of Zeus.

Following the Greeks, the Romans adopted the same festival, the predecessor of modern Christmas-tide, renamed it Saturnalia in honor of Saturn, their father-god and equivalent of the Greek’s Kronos. They decorated their houses with greens and lights and exchanged gifts. They gave coins for prosperity, pastries for happiness and lamps to light one's journey through life. They decorated their trees with bits of metal and candles in honor of their sun god.

Trees — especially the conifer or evergreen — were objects of sacred significance in many ancient cultures. The Norse religion involved worship in sacred groves, which were trees planted to simulate the walls of a temple. This connects the tree to temple building traditions. Indeed, nearly all temples, ancient and modern, are adorned with gardens, as is the case on Temple Square.

The Canaanites, too, had sacred groves for worship, and the disobedient nation of Israel adopted this form of worship at the outset of their wanderings out of Palestine.

"For they also built them high places, and images, and groves, on every high hill, and under every green tree." (1 Kings 14:23. See also 2 Kings 17:9, 10.)

"Then shall ye know that I am the Lord, when their slain men shall be among their idols round about their altars, upon every high hill, in all the tops of the mountains, and under every green tree, and under every thick oak, the place where they did offer sweet savour to all their idols." (Ezekiel 6:13.)

We learn also that Israel’s neighbors practiced a custom startlingly similar to our practice of putting up Christmas trees. "Thus saith the LORD, Learn not the way of the heathen, and be not dismayed at the signs of heaven; for the heathen are dismayed at them. For the customs of the people are vain: for one cutteth a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the axe. They deck it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, that it move not." (Jeremiah 10:2-4.)

This passage also alludes to the belief in ancient cultures that the tree was symbolic of something cosmological or sky-based. The mention of the "signs of heaven" in the above verse is our clue. As with so many ancient religious or sacred symbols, the "celestial" or "heavenly" tree was an integral part of archaic cultures' star worship.

In Norse mythology, the great ash tree, Yggdrasil, connects the underworld and heaven with its roots and boughs. It’s also called the World Tree, which many ancient cultural traditions remember and reverence, that links heaven and Earth and shelters all the world. The mythical world tree was said to grow from the Earth’s pole and spread its branches among the stars. This "celestial tree" or "tree of life" — a term familiar to Latter-day Saints — was central to astral worship, as Jeremiah pointed out. It’s also the reason we put a star at the top of our Christmas tree.

To Norsemen, sprigs of evergreen holly symbolized the revival of the sun god Balder, who was originally the familiar Baal, sky god of the Old Testament.

Also in the Old Testament, trees are associated with the ancient Canaanite religion devoted to the mother goddess Asherah(Ashtoreth, Ishtar, "star"), which the Israelites, intent on establishing their monotheistic cult of Yahweh, sought to suppress. The cult celebrated Asherah and her consort Baal in high places, on the tops of hills and mountains, where altars dedicated to Baal and carved wooden poles or statues of Asherah (also translated as grove, or wood, or tree) were located.

The significance of trees in ancient Assyria, the acknowledged home of Ishtar or "star" worship, is shown in the numerous reliefs of winged deities watering or protecting sacred trees. Sacred trees, or trees of life, were associated in Ancient Assyria with the worship of the god Enlil, yet another sky god.

So, our Christmas tree has a long and ancient tradition.

The evergreen Christmas tree also represents "World Tree" or "World Axis." The "Star of Guidance" that crowns the Christmas tree is also related to the North Star, Polaris. This natural compatibility of Christmas celebration with late December and beliefs about the evergreen tree, the North Pole, and the spirit called Father Winter, which survives in today’s Santa Claus, are evolutions of ancient tradition.

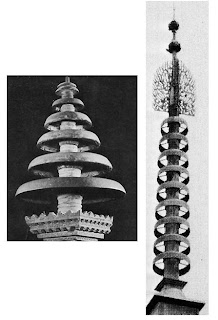

Notably, the six primary spires on the Salt Lake Temple are the symbolic equivalent of our Christmas tree. A round ball, the equivalent of a star on our tree, tops their conical shape.

Indeed, one of them bears an angel in place of the star, just as do many of our Christmas trees.

Just as the image of the star and the angel are interchangeable in ancient traditions, so too in modern Christmas tree decoration and temple iconography.

In Europe as well as in Asia, the Sacred Tree was considered to be the living image of the axis mundi or "Axis of the World," a figurative or imaginary still point or vertical shaft around which the world turns.

The North Star, Polaris, is the celestial placeholder for that sacred spot in the sky. It’s the only star in the sky that never moves. Throughout the night and year, all the stars move in circles around Polaris, called the pole star since it is located directly over the Earth’s north pole. As the night progresses, the stars will slowly move from east to west, circling around the pole star, due to the Earth’s rotation. Hence, all ancient cultures held that spot in the sky as sacred.

They also associated the pole star with the World Tree or Tree of Life and the central axis of the universe. In tradition, the top of the World Tree touched the North Star. This is the true meaning of the star on top of the modern Christmas tree, and also the reason that Santa makes his home at the North Pole in Christmas tradition.

In South Asia, traditions concerning the enchanted World Tree or World Axis have taken somewhat different forms. And yet, despite the differences, certain common patterns persist. The sacred tree, the vertical World Axis or stambha or stupa and the generous spirit from the far north are all features of pan-Indian culture that derive, most probably, from the same traditional sources as those of Western cultures.

The precedence of the cosmic center among the great ancient cultures has been noted and documented by many scholars. Almost a hundred years ago, William F. Warren, in his groundbreaking work, Paradise Found, identified the celestial pole as the home of the supreme god of ancient races. "The religions of all ancient nations ... associate the abode of the supreme God with the North Pole, the centre of heaven; or with the celestial space immediately surrounding it."

In a general survey of ancient language, symbolism, and mythology, John O’Neill (Night of the Gods) asserted that mankind’s oldest religions centered on a god of the celestial pole.

Latter-day Saints should note that, in keeping with ancient astral tradition, the constellation Ursa Major or Big Dipper, the traditional locator for the Pole Star, is depicted on the west wall of the Salt Lake Temple where it is positioned so as to ‘point’ to the northern sky and the polar star, Polaris.

Also seen immediately above these star stones are the Saturn Stones, circles with a ring.

This is no mere oddity or casual coincidence. As Nibley pointed out, the temple is an earthly replica of the heavens. It puts the uniquely modern temple squarely in the heart of ancient tradition — especially Christmas tradition. Certainly, it speaks to the reverence which modern temple builders placed on the star Polaris and its traditional role in ancient cultures worldwide.

Though it may seem completely odd to us, the Romans, who called themselves "Saturnians" and celebrated Saturnalia at the winter solstice, also placed their god Helios at the heavenly pole where Polaris now sits. In their pantheon, Helios was called the central sun, the axis of the celestial revolutions. But, Helios was also called Saturn.

All Greek astronomical traditions agreed that their god, Kronos, was originally the planet Saturn. What is now the sixth planet from the Sun stands at the center of the Greek paradise myth. According to their traditions, Kronos, the planet Saturn, ruled the heavens for a period, presiding over the Golden Age, then departed as the heavens fell into confusion.

Likewise, the Assyrians placed their central sun, Shamash, at the pole. But, they also asserted that Shamash was Saturn.

A stunning example of the polar Saturn is provided in Chinese astronomy, where the distant planet was called “the genie of the pivot” (Santa Claus?). Saturn was believed to have his station at the pole, according to the eminent authority on Chinese astronomy, Gustav Schlegel. In the words of Leopold deSaussure, Saturn was "the planet of the center, corresponding to the emperor on earth, thus to the polar star of heaven."

Finally, the Egyptian god Atum-Ra was said to be a central sun, standing atop the world pole. But, their traditions also depict Atum-Ra as Saturn.

As peculiar as this tradition of Saturn at the pole may appear to us, it has been acknowledged by more than one authority, including Leopold de Saussure. The principle also figured prominently in the recent work of the historian of science, Giorgio de Santillana and the ethnologist Hertha von Dechend, authors of Hamlet’s Mill. According to an ancient astronomical tradition, the authors suggest, Saturn originally ruled from the celestial pole.

It is also known that Latin poets remembered Saturn as god of "the steadfast star," the very phrase used for the pole star in virtually every ancient astronomy.

Manly P. Hall, noted authority on ancient belief systems wrote, "Saturn, the old man who lives at the north pole, and brings with him to the children of men a sprig of evergreen (the Christmas tree), is familiar to the little folks under the name of Santa Claus."

Santa Claus, descending yearly from his polar home to distribute gifts around the world, is a muffled echo of the Universal Monarch, Saturn, spreading miraculous good fortune. But while the earlier traditions place this sky god at the celestial pole, popular tradition now locates Santa Claus at the geographical pole — a telling example of originally celestial gods being brought down to earth.

The origin of Santa Claus imagery can be readily seen in Egyptian religious art. Atum/Ra, the god of the north, stands in his celestial boat, bark or ark, pulled across heaven by servants or souls.

The Egyptian image metamorphosed over time and across several ancient cultures to become, in Nordic cultures, the old man of the north, Santa Claus, pulled in a sleigh by reindeer.

It is at this point that these ancient traditions most specifically intersect with modern temple symbolism.

Most Saints know of the Sun Stones depicted on the Salt Lake Temple. Given the traditions of the Egyptians, Assyrians and the Romans, it seems likely that those Sun Stones, like the Big Dipper, were placed there in recognition of the ancient traditions, which declared that a "sun" was once positioned at the celestial pole.

Additionally, most Saints are unaware that there are Saturn Stones in the Salt Lake Temple. The original architectural renderings of the building by Truman O. Angel, clearly depicted a planet with two rings around it at the top of each south wall buttress.

Note that there is no such symbol on the Salt Lake Temple as it was finally erected, as we see it today. Instead, a repeated symbol (called a 'frieze' in architecture) of a circle with a ring around it (the traditional symbol for Saturn) was installed to replace the original icon. This circle frieze can be seen on the parapet stringcourse, immediately below the three towers at each end of the temple, and is still referred to in LDS literature and tradition as Saturn Stones.

Just as the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans worshiped a central sun that we, today, can identify from cross-cultural comparisons as Saturn, the various 'stones' on the Salt Lake Temple also celebrate that connection, once again correlating temple iconography with ancient, traditional symbolism that gave rise to our Christmas traditions.

It’s no stretch to see that modern prophets would employ the ancient, traditional symbolism of antiquity on a modern temple. The fact that they would properly use the traditional, sacred, religious icons from the past serves to strengthen Joseph Smith’s and Brigham Young’s claims to being prophets of God.

So, what should we make of Christmas with all its pagan symbolism and motifs? If modern prophets chose to memorialize the symbols of ancient traditions in latter-day temples, then who are we to reject those same symbols and traditions in our Christmas celebration?

© Anthony E. Larson, 2005