Every published effort to explain the meaning and purpose of such symbolism, typical in early temple architecture, is limited to unbridled speculation on the authors’ part as to the possible meaning of this symbol or that. Yet, few of their notions leave the reader satisfied or better informed. Such scholarly efforts fall far short of their stated expository goal, excusing their failure by bemoaning the fact that no early LDS prophet, authority or architect ever bothered to explain the symbols they employed.

Scholarly ignorance

All the verbal shoulder shrugging done by LDS scholars when it comes to modern temple symbology is very telling, indeed. It means a vital part of their gospel training has been woefully neglected. If they had taken the time and made the effort to understand Joseph Smith’s view of ancient history, the symbols would be full of meaning for them.

Ironically, from this author’s point of view, the gospel, the scriptures and the teachings of modern prophets provide ample explanation if seen in the proper perspective and context. Early church authorities made no comment on temple symbology because it dealt with sacred themes. Also, they felt no comment was needed; explanation is unnecessary for the properly initiated. The answer is there for all to see; yet modern Saints fail to see it because they fail to understand what they have been taught.

The temple as a parable

Like scriptural parables, the meaning of temple iconography is denied to those who fail to study the gospel in depth. To most, the symbols simply appear to be decorative, indicative of nothing important. While anyone can perceive the meaning of parables and symbols on a superficial level (as every scholarly effort in that vein proves), there is a more profound message for those who care to look more closely.

In order to understand the iconography of the temples he inspired, one must understand Joseph Smith’s view of history and the heavens. (After all, the symbols are drawn from astral bodies and phenomenon.) From a few, key statements made by the prophet and his closest confidants, together with the acknowledgment that he held a cosmological view of Earth’s past and future that differs significantly from today’s mainstream views, one can begin to understand the elements he employed in temple architecture. As long as LDS scholars and church members fail to give credence to the catastrophic history of planet Earth, as long as they fail to connect that history with scriptural events and imagery, as long as they fail to grasp Joseph Smith’s view of the ancient cosmos, the iconography of the Salt Lake Temple will remain a mystery to them.

The Freemason connection

Most scholarly expositions on LDS temple iconography are largely vacuous discussions of how the symbols were likely borrowed from the Masons by early church leaders who dabbled in Masonry, including the Prophet Joseph Smith himself. This type of apologist drivel casts the church and its founder in an indefensible position: The Prophet is made to look like a plagiarist and LDS temple iconography and ceremony made to be borrowed, ‘used goods.’ Neither is true.

What Mormon and Masonic temples have in common stems only from a common origin, the very things they share with ancient temples and religious architecture the world over. Both Masonry and Mormonism arose in the Anglo-Saxon culture (Masonry in 13th century Europe, Mormonism in 19th century America), hence it was wise on Joseph’s part to employ many similarities so that the temple would seem, at least, somewhat culturally familiar to 19th century Americans. While Joseph adapted elements familiar to the culture he lived in, he could have just as easily employed elements from Egyptian, Mayan, Celtic, Oriental or Nordic traditions. However, that would have made the temple seem totally foreign to most newly converted Mormons.

The astral connection

Among LDS scholars, Nibley alone makes the point that modern temple iconography shares that of ancient temples. Indeed, the title of his book tells the story: Temple and Cosmos. While he clearly sees that temple architecture and symbolism, ancient and modern, reflected astronomical values, Nibley fails to make the vital connection to Saturnian traditions, to the appearance of the ancient heavens as opposed to our modern heavens. Yet, that is the final key to interpreting all temple architecture and iconography. From Stonehenge to Tiahuanaco, to Angkor Thom, to the Parthenon, to the pyramids on the Geza plateau and the enigmatic Sphinx, to Teotiuacan and Chichen Itza, to the Nauvoo temple and the Salt Lake Temple, they all share one commonality: They were designed and adorned to reflect the appearance of the heavens, both ancient and modern.

Temple symbolism, ancient and modern

The symbols employed on Mormon temples share a common origin with the symbolism employed in ancient temples the world over. No matter the culture, no matter the structure, they were all erected to memorialize (remember or reconstruct) the realities in Earth’s ancient heavens as much as the heavens we have now. Additionally, temples have always incorporated features of the current arrangement of the heavens when the temple was built as well. In that regard, temples are an amalgam of the ancient heavens and the present heavens. This Nibley reiterates time and again.

Failure to acknowledge, as the Apostle Peter taught, that “the world that then was ... perished” (2 Peter 3:6) and “the heavens and the earth, which are now” (2 Peter 3:7) are vastly different from the originals has created endless confusion in the sciences and in our understanding of scripture and temple iconography.

Astral temples

Scholars readily acknowledge the astral or cosmic connections in ancient temples. Alignments with the equinox, solstices, constellations, the Sun, Moon, Venus, Mars and other celestial objects are the subjects of endless discussion. Yet, these same scholars utterly fail to recognize that the gods and goddesses, dragons, demons and devils memorialized in those temples were originally astral, based on something actually seen in the heavens anciently. Once one accepts the premise that imposing, impressive planets were the original powers that once dominated Earth’s heavens, that their motions, metamorphoses and interactions gave rise to all ancient myth and symbolism, then the rest falls into place automatically.

Modern temples are no exception to this rule. Latter-day Saints readily acknowledge the astral connections of most symbols employed in the Salt Lake Temple (that would be hard to deny), yet they utterly fail to recognize their connection to the same symbolism used in scriptural rhetoric and in ancient architecture. Indeed, uninformed, modern eyes take most of the symbolic iconography to be nothing more than stylistic decorations.

The mysterious Saturnstones

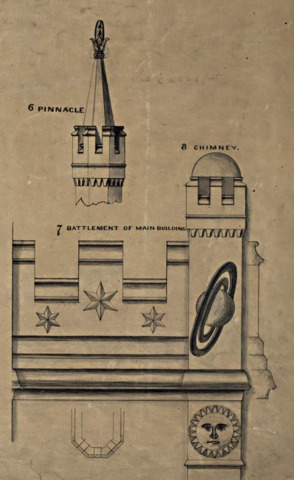

All Latter-day Saints are acquainted with the most familiar icons of the Salt Lake Temple. There are Sunstones, Moonstones, Earthstones and Starstones. What most Saints do not know is that the original architectural drawings by Truman O. Angell, temple architect, called for Saturnstones, a depiction of a planet with two rings around it, located at the top of the buttresses, above the Sunstones, on the long south wall of the temple.

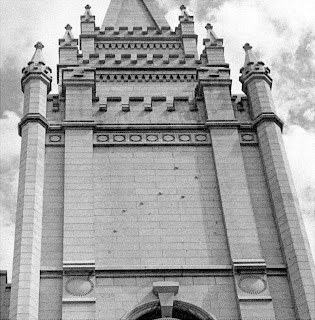

Note that there is no such symbol on the Salt Lake Temple as it was finally erected, as we see it today. Instead, a repeated symbol (called a ‘frieze’ in architecture) of a circle with a ring around it was inaugurated to replace the original icon.

This circle frieze, as depicted here, can be seen on the parapet stringcourse, immediately below the three towers at each end of the temple, and is still referred to as the Saturnstones.

This symbol, too, is in accord with ancient iconography. It is the basic symbol for the Saturnian configuration, and is related to the Eye of God symbol.

Apparently, a decision was made to eliminate the Saturn icon sometime between the creation of the original plans for the temple and its final construction. No reason was ever given, and LDS scholars are at a loss to explain why the change was made. But it is this author’s contention that using a Saturn symbol was making too plain a truth that the church was not willing to explain openly.

As noted elsewhere by this author, the truth of Saturn’s dominance in Earth’s ancient heavens was the great, sacred secret of antiquity. It was told only in the most sacred precincts of ancient ritual centers. While the outward symbolism of ancient architecture, symbology and ritual endlessly reiterated the truths of Earth’s ancient skies, the names or titles used publicly to designate these icons or deities did not directly connect them to the actual planets themselves. This was withheld, saved for more sacred moments. It is for this same reason, for example, that the sacred name of God (eeeeaaaahoooowaaayeeee) was spoken only in the Holy of Holies in ancient Israelite temples, yet the name Yahweh was commonly known, used in names and expletives.

One can only speculate that, in like manner, Brigham Young, who was intimately involved in every detail of the Salt Lake Temple’s conception and construction, had learned of Saturn’s true role in Earth’s past from Joseph Smith. While Brigham’s initial inclination, likely, was to display that truth iconographically on the walls of the temple, a change of heart led him to alter the symbolic scheme. He may have felt that this truth was too much for Saints and Gentiles alike. If so, he was true to the pattern of secrecy set down by every other temple-building culture in history.

Location, location, location

It is striking that an icon of the planet Saturn should have occupied the highest point on the buttresses.

Again, scholars seem puzzled by its presence and location, wondering why Saturn was selected since there is apparently nothing in Mormon theology that would designate the planet worthy of elevated positioning on a modern temple.

One scholar stumbled on the truth when he noted that Saturn may have been selected to represent Kolob since it was the most noteworthy planet in the solar system, making it a symbolic match for the “great” star written of by Abraham. Ironically, the scholar was closer than he knew. As explained elsewhere by this author, Kolob was one of many Egyptian designations of the ancient Saturnian configuration of planets. For that reason the Saturnstones were properly included in the iconography of a latter-day temple, located above all the other icons at the highest point on the wall because Saturn once stood above all other planets or stars.

Looking north

Also noteworthy is the fact that the original drawings depicted the Saturnstones only on the south wall of the temple, not on the north, east or west walls. In this, the temple’s designers were true to the ancient order of things.

In antiquity, when Saturn dominated earthly skies, one could only see Saturn when facing north; facing south would have put Saturn behind the observer. Hence, a depiction of Saturn on a modern temple should properly be located only on a south-facing wall, so that it is only seen when facing the south side of the temple, where the viewer is looking northward, as he would have done to see Saturn in antiquity. Thus, the location of the symbol properly orients the observer northward. It would be, therefore, completely inappropriate to depict Saturn on an east, west or north-facing wall.

More pointer stars

This brings us to the depiction of Ursa Major or the Big Dipper high on the west wall of the temple.

These stars are depicted there, again, to point the eye of the viewer to the north, the location of Saturn in antiquity.

The temple’s designers wished, again, to properly orient the viewer. As one stands looking up at the temple’s west wall, he or she is facing east with the north to his left. The stars forming the Big Dipper are arranged on the temple, as they are in the heavens, so as to point to the North Star, Polaris, on the viewer’s left, the one and only star in the heavens that remains immobile, the one and only star to which a fixed symbol could constantly point. Thus, Polaris becomes a symbolic substitute for the ancient anchor of the heavens, Saturn.

The Big Dipper is traditionally used as a pointer constellation for the North Star. Thus, all who saw the Big Dipper constellation icon on the wall immediately knew it pointed to Polaris. It serves as a universal signpost, in a universal, symbolic language. Additionally, the selection of Polaris, the North Star, is most appropriate because, as was true of ancient Saturn, it is the only apparently fixed object in the sky, the polar anchor around which all heaven turns. So, too, was ancient Saturn depicted as ever turning, yet never moving, fixed and immovable.

Orienting observers

The location of the original Saturnstones on the south wall and the existing star icons on the west wall both direct the observer’s attention to the north, the original location of the Saturnian configuration of planets in antiquity. Thus we see how elements of the present heavens are combined with those of antiquity in this modern temple, as they were with all its ancient predecessors. This also serves to suggest that most, if not all, of the other temple icons depict some aspect of that ancient planetary alignment, the original cosmos, the first heavens.

So we see that Nibley was accurate in his assessment of the temple as a representation of the cosmos. More accurately, it depicts elements of the ancient sky and the modern sky - what the ancients meant by "cosmos." Thus, the temple becomes a virtual road map of the ancient heavens, pointing the observer to the original elements that are no longer seen.

To be continued ...

© Anthony E. Larson, 2001