Science as a Personal Journey

By Chris Reeve

There is something you need to know about scientific controversies:

Your own personal reaction to controversial science says much about the depth of your own thinking and your own propensity to lead. When we treat controversies as an open-ended clash of worldviews where the answer is not already known, we sharpen our critical voice, we develop the habits of higher-order thinking, and we open the door to becoming effective leaders.

There is “normal” science, and then there is controversial science. Normal science is science which has largely stabilized because there’s a general absence of anomalous observations. It can be reliably treated as a body of knowledge.

But, what about science which has been contested?

When science becomes controversial, we have to prepare for the possibility that there may be a mistake in our body of knowledge. To the extent that we refuse to do so, we abandon the aspect of scientific theory which distinguishes it from other aspects of our culture — its provisional nature.

What has been overlooked in the unfortunate science journalism and science education which dominate today is that there are processes happening in each of our own individual minds which greatly resemble this never-ending process of change we see at play on the larger stage of the scientific world. And just the same, when we fail to actively engage with controversial science at the personal level, we are diminishing our own personal propensity for change — which sets into motion habits which then limit our own leadership capabilities.

Much can be said about the two diagrams you see in this article.

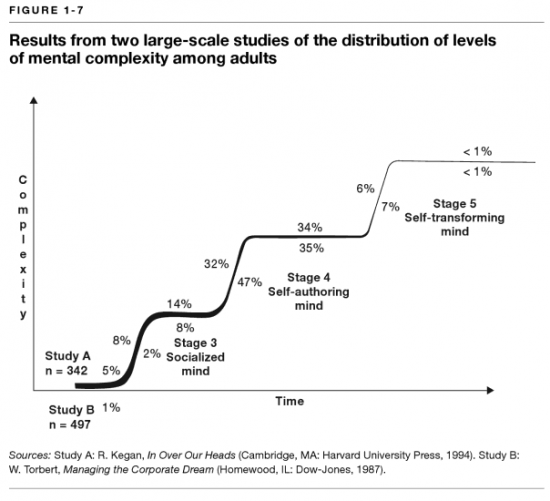

The first diagram relays the results of two separate studies which collectively suggest that only a very small portion of the population — around 8% — will ever learn to question their own personal worldview (the “self-transforming mindset”).

We’d all be wise to ask why these numbers are so low, and there is a very simple answer in the diagram below (take your time with studying it, for it may be the most important thing you see today).

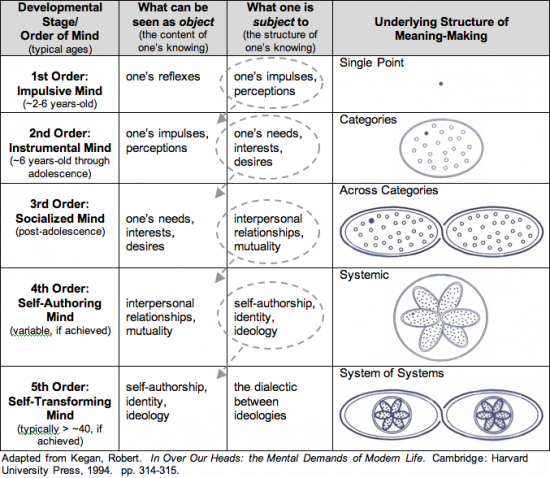

The heart of the problem is this: to get to the true complexity of a scientific debate, a person has to be willing to entertain the notion that there exists a mistake in their own personal knowledge. And as the diagram on the right shows, to succeed at critiquing ourselves and our beliefs, we must ourselves go through a personal transformation. We have to cross what is called the subject-object barrier, from a state where we are in the grips of our existing worldview (e.g., subject to the textbook theory) to a state where we can discuss this mainstream worldview as an object.

We are talking about two different minds here: It is not merely a technical challenge to cross the subject-object barrier; it is an adjustment to the machinery of the mind itself. There’s not — yet — any place that a person can go to systematically learn to transition the subject-object barrier. This makes it a very personal journey.

We call the people who successfully learn to do this “leaders”, and in times of turmoil, we rely very heavily upon their own personal decision to modify their own mental machinery (to undergo their own “paradigm change”). What must be emphasized is that when the controversy of controversial science is minimized, in order to continue treating the contested science as a body of knowledge, the person who is doing this is deciding to forgo this personal journey.

In most cases, they will not understand the implications of the choice they’re making — that what they are giving up is an opportunity to develop their leadership skill; and what they are receiving, in return, is stability and a sense of security about the world which is threatened by the new worldview.

A recent article by a successful self-made entrepreneur demonstrates that the principles which dictate our personal success or failure in life completely transcend the limited niche topic of scientific controversies. These are in fact general principles which we can apply to any endeavor:

A Self-Made Billionaire Reveals the 1 Mental Hurdle That You Must Overcome to Reach Your Potential

People who can do this are winners; those who can’t are losers, according to the world’s most influential hedge fund entrepreneur.

Billionaire Ray Dalio founded Bridgewater, one of the world’s largest and best-performing hedge funds. A true entrepreneurial success story, Dalio started his company in a two-bedroom apartment. He was a self-described ordinary kid and worse-than-ordinary student. Forty-two years after starting his company, Dalio decided to share his success secrets in his new book, Principles …

Dalio’s advice: Be radically open-minded

Good decisions aren’t necessarily the ones that stroke your ego. A good decision is what’s best for you and your company. To make good decisions, argues Dalio, a person must have the ability to explore different points of view and different possibilities, regardless of whether it hurts your ego.

Ask any of your friends or any entrepreneur if he or she is open-minded, and most — if not all — will say they are. But are they? Are you? According to Dalio, here are some cues that will tell if you are truly open-minded.

– Close-minded people don’t want their ideas challenged; open-minded people are not angry when someone disagrees.

– Close-minded people are more likely to make statements than ask questions; open-minded people genuinely believe they could be wrong.

– Close-minded people focus much more on being understood than on understanding others; open-minded people always feel compelled to see things through others’ eyes.

– Close-minded people lack a deep sense of humility; open-minded people approach everything with a deep-seated fear that they may be wrong.

Dalio believes that recognizing these traits in yourself is just the first step. The second step is recognizing them in others. Once you do, “surround yourself with the open-minded ones,” he says.

According to Dalio, it’s critical to reframe a disagreement not as a threat, which is what your primitive brain sees, but as an opportunity to learn. “People who change their minds because they learned something are winners, whereas those who stubbornly refuse to learn are the losers,” he says. Dalio points out that being open-minded doesn’t mean that you blindly accept another person’s conclusions. He recommends being open-minded and assertive at the same time. “You should hold and explore conflicting possibilities in your mind while moving fluidly toward whatever is likely to be true based on what you learn,” he says.

Dalio offers several recommendations to help you develop the habit of being radically open-minded. Among them:

“Sincerely believe that you might not know the best possible path.” Dalio says that recognizing what you don’t know is more important than whatever it is you know for sure.

“Recognize that decision-making is a two-step process: First, take in all the relevant information, then decide.” Dalio says it’s here that many entrepreneurs get tripped up.¬ Most people are reluctant to consider information that is inconsistent with their worldview or the conclusion they’ve already arrived at.

“Remember that you’re looking for the best answer, not simply the best answer that you can come up with yourself.” This last piece of advice could be the most important. Dalio points out that when two people disagree, there is a good chance that one of them is wrong. What if it’s you?

… Disagreements, debate, and feedback all serve the ultimate purpose–to reach the best decision. Setting aside your ego could be your ultimate competitive advantage. “If you are too proud of what you know … you will learn less, make inferior decisions, and fall short of your potential,” says Dalio.

A very different 2016 article carried by Vice.com is more typical of what we see with science journalism today: It is like many others in the sense that it invites us to adopt an opinion on a particularly controversial subject — in this case, electricity in space — in such a way that we completely avoid the journey.

“‘Electric universe’ theory is at odds with everything modern science has determined about the universe …

‘At best, the ‘electric universe’ is a solution in search of a problem; it seeks to explain things we already understand very well through gravity, plasma and nuclear physics, and the like,’ said astronomer Phil Plait, who runs the blog Bad Astronomy at Slate. ‘At worst it’s sheer crackpottery like homeopathy and astrology, making claims clearly contradicted by the evidence.’ …

But most in the astronomy ‘establishment’ or ‘NASA,’ which seems to be the blanket EU term for a conglomeration of mainstream astronomers, would say EU doesn’t deserve refutation …

‘We know stars generate energy through nuclear fusion, not plasma discharge; we know craters are formed from asteroid and comet impacts, not huge electric arcs; we absolutely know that special and general relativity work, despite some EU proponents’ claims,’ said Plait, who has tangled with EU commenters a time or two. ‘From what I’ve seen, most EU claims are on the cranky end of [the] scale. That’s why most astronomers ignore it: No evidence for it, tons of evidence against it, and no support mathematically or physically.'”

It’s one of the numerous articles that are posted online every day which seeks to devalue the personal journey that an individual goes through when they start to question the dominant worldviews.

On the surface, what Phil Plait and the Vice article’s author, Sarah Scoles, offer us is an effortless way out of a complex controversy; they are giving us a sense of security that our knowledge is correct. But, as the self-made billionaire hedge fund entrepreneur, Ray Dalio, explicitly demonstrates to us through his success is that the Vice article is inviting us to partake in habits that actually preclude our own long-term success. We each have an immunity to change, and what that means is that questioning worldviews is a skill which we can only develop through practice.

The reason why we must personally engage scientific controversies is that holding two opposing thoughts in our heads goes against nearly everything we have been taught — and yet, in a general sense, that is precisely the skill which we must cultivate in order to transition the subject-object barrier to higher forms of thinking. The essence of leadership is that when the crucial moment to switch from one belief system to another arrives, we are already well-prepared for the situation; we’ve been down this path before — or at least something like it. Plait and Scoles are teaching their readers to become pundits, not thought leaders — dependent upon other people (like Plait) for leadership.

If you like, the numerous debates over the science can in this view be thought of as just the vehicle which enables our own personal journey to higher-order thinking. There are no shortcuts here: either you are practicing critical thinking in the sciences every day — in which case you are preparing yourself to meaningfully participate in the history of the world, while also preparing yourself for success — or you are adopting wholesale, on faith, the claims of expert pundits — in a sense, actively culturing your own dependence, lack of participation in the world’s current historical moment, lack of creativity, and inevitable failure to think ahead of the crowd.

This is the inherent contradiction of controversial science: you are either on a quest for a worldview which you can feel secure and certain about (benefiting modern science as a reliable cog in the larger machine), or you are in it for the personal journey — to indirectly enrich society through first enriching yourself.

It’s your call.

Chris Reeve has Bachelor of Science Degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering from Carnegie Mellon University and has spent thousands of hours discussing the Electric Universe on a number of scientific and other forums. He is building a platform to crowdsource information about scientific controversies. He learned to code three years ago for the specific purpose of creating this platform. To learn more about his project, visit https://www.patreon.com/controversiesofscience

Chris Reeve has Bachelor of Science Degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering from Carnegie Mellon University and has spent thousands of hours discussing the Electric Universe on a number of scientific and other forums. He is building a platform to crowdsource information about scientific controversies. He learned to code three years ago for the specific purpose of creating this platform. To learn more about his project, visit https://www.patreon.com/controversiesofscience

Photo Credit: LoboStudio Hamburg on Unsplash

The ideas expressed in Thunderblogs do not necessarily express the views of T-Bolts Group Inc or The Thunderbolts ProjectTM.