I. Saturn’s Cosmos

The ancients preserved more than mythical-historical accounts of Saturn’s rule. From one section of the world to another the planet-god’s worshippers drew pictures of the Saturnian configuration, and these pictures become the universal signs and symbols of antiquity.

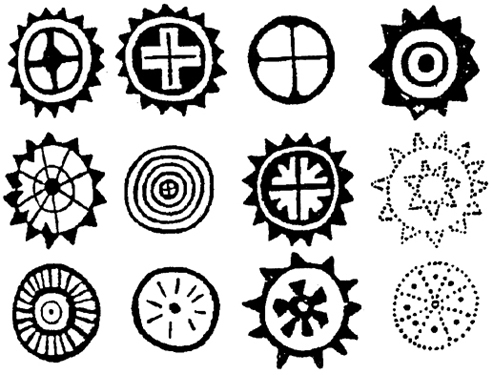

In the global lexicon of symbols the three most common images are the enclosed sun , the sun-cross , and the enclosed sun-cross . It appears that every ancient race revered these signs as images of the preeminent cosmic power. In Mesopotamia and Egypt the signs occur in the earliest period.

Prehistoric pottery and rock carvings from Crete, China, Scandinavia, Africa, Russia, Polynesia, and the Americas suggest that numerous ancient rites centered on these simple forms—which became the most venerated images in the first hieroglyphic alphabets.

But what did these signs signify to the ancients? With scarcely a dissenting voice, scholars routinely tag them as solar symbols. They tell us that such renderings of the sun are perfectly natural (that is, they must be “natural” ways of representing the sun because one sees the signs everywhere!)

Though everyone seems to agree on the solar origins,271 many disagree as to what the signs depict. In the image, does the outer band represent a parhelion (atmospherically caused halo around the sun)? Or does it stand for “the circle of the sky”? Some commentators suggest that the outer circle is itself the sun, leaving open the question of the meaning of the enclosed dot.272

Similarly, in evaluating the sign , the experts cannot agree whether the four arms of the cross denote rays of the sun or four quarters of the world. It is also said that the four arms depict spokes of an imagined sun wheel rolling across the sky each day.

Is it necessary to point out that these differences of opinion immediately throw into question the common claim that the signs are natural solar emblems? So long as the meaning is uncertain one can hardly state that a symbol is a natural expression of anything. Yet surely those experts who debate the significance of the “sun” symbols must wonder why the ancients, with one accord, inscribed the same images the world over.

Consider the relatively complex sign . The basic form occurs along with many variants on every continent. Whatever it may signify, it is more than a simple drawing of the sun. If it is a solar image, then one must assume not only that the sun worshippers around the world instinctively adopted the sun to a more complicated abstract form, but that every ancient sun-cult drew upon the same abstraction. Why?

The enclosed sun-cross is not an abstraction. It simply records what the ancients originally saw. It is a literal drawing of the polar sun, passed down from earliest antiquity: the image of Saturn, the Universal Monarch.

Rarely do archaeologists, seeking to interpret the widespread “sun” symbols, consult ancient mythology. Yet the myths explain the symbols, and the symbols illuminate the myths. Largely overlooked by archaeologists are the hundreds upon hundreds of

myths and liturgies focusing on the cosmic images

, and . Ancient sources reveal a world-wide concern

with a concrete celestial form—an ideal configuration identified as the great god and his heavenly dwelling. The subject is not the present world order, but the former. The symbols, legends, and sacred hymns attempt to preserve a memory of Saturn and the primeval Cosmos.

The Enclosed Sun

When Saturn appeared alone in the cosmic waters, a brilliant band congealed around the god as his celestial “island.” This band was the original Cosmos, often portrayed as a revolving egg, a coil of rope, a belt or a shield enclosing the central sun.

The sacred hymns and creation legends of ancient Egypt say that when the creator arose from the cosmic sea, a vast circle appeared around the god, forming the original Place—“the place of the primeval time,” or “the Province of the

Beginning.”273 This primeval dwelling was the “island of Hetep [Rest],”274 a steadfast, revolving enclosure. Egyptian texts of all periods offer vivid images of this enclosure on the waters—called “the golden Pai-land,” the “Island of Fire,” “the divine emerging primeval island,” or “the island emerging in Nun [the cosmic waters].”275

Diverse sources agree that the island of creation stood at the cosmic centre and that it was the residence of the creator himself, the central sun. Thus, while Osiris is the “motionless heart” in the Island of Fire, Atum, the stationary Heart of Heaven, is “the Sole One who is alone . . . , who made his heart in the Island of Fire.”276

In the following pages I shall attempt to show that Egyptian sources depict the band as something seen—the god’s visible dwelling in heaven. Indeed, the Egyptians—and all other ancient races—were so preoccupied with the Saturnian band that they elaborated a vast symbolism presenting the same enclosure under wide-ranging mythical forms.

Yet standard treatments of ancient myth and religion say little or nothing of the enclosure. And even less do writers on the subject seem aware that the pictograph of the enclosure sun is a straightforward portrait of Saturn and his legendary home.

It is not for want of evidence that the experts have missed this connection. The only obstacle is the a priori world view of the researchers themselves—who presuppose that all references to the primordial light god can only signify the solar orb. In connection with our sun today, the ancient language of the enclosure will appear esoteric or meaningless.

Of Re, the Coffin Texts say, “We honour him in the sacred enclosure.”277 Re is the “sender forth of light into his Circle.”278 “I am the One who is in his Circle,” he announces.279 What could this terminology signify in relationship to the solar orb? Since our sun possesses no perceptible relationship to an enclosure or circle, the translators will likely ignore the terms or contrive a complicated metaphysical concept to explain them.

Though the Egyptian hieroglyph for Re is , and though this sign, taken literally, immediately illuminates the foregoing references, no one seems inclined to take the signor the texts—literally.

To the enclosure round the sun the Egyptians gave the name Aten, a term familiar to every student of Egyptian religion. “Spacious is your seat within the Aten,” reads the Coffin Texts.280 One of Re’s titles is am aten-f, the dweller in his Aten.” Both Atum and Horus possess the same title. Similarly, the Book of the Dead invokes Osiris: “O great god who livest in thy divine Aten.”281 Since the Egyptian pictograph of the Aten is or , it should be clear that the term refers to a circular enclosure housing the sun-god.

But from the beginning Egyptologists have attempted to explain the Aten as the sun itself, translating the word as “the solar disk.” Rather than clarify the Egyptian concept, such a translation only confuses the sun-god with his celestial dwelling. One Egyptologist, for example, states that the Aten was the sun, and that the sun was conceived as “the window in heaven through which the unknown god, ‘Lord of the Disk,’ shed a portion of his radiance upon the world.”282

Having identified the Aten with the solar orb, the writer concludes that the god who resides in the Aten is an invisible god. Budge voices a similar opinion when he calls the Aten “the material body of the sun wherein dwelt the god Re”283 as if Re himself were an invisible power and the solar orb the visible emanation and dwelling of the god.

It is impossible to reconcile such metaphysical interpretations with the concrete imagery of the Aten in Egyptian texts. The Aten is indeed the visible “window in heaven” and the “body of the sun,” but this “window” or “body” is surely nor the

solar orb. It is, as the Aten sign (

) indicates, a band housing the sun. And the primeval “sun” is Saturn.

The same misunderstanding occurs in the case of the Egyptian terms khu and khut. The terms refer to “the circle of glory” or the “brilliant circle,” conceived as a fixed place” —the place where the [primeval] sun shines forth.” Though the Egyptians regarded this circle as the visible emanation of the creator, standard translations render khu as “Spirit” or “Soul” (implying an unseen power) and khut as “horizon” (suggesting the place of the solar sunrise). Both translations violate the literal sense of the words: literally, the khut (written with the sign ) is the “Mount of Glory.”

The circle of the khu or khut was the “glory,” “halo,” “nimbus,” or “aureole” of the creator—what the Hebrews called the Shekinah (the encircling “glory” of God) and the Greeks stephanos (circle or crown of “glory”). Indeed, every figure of the creator stands within the luminous ring, always considered as his own emanation. The band is not only the god’s “halo,” but his dwelling at

the cosmic centre.284 “In diagrams of the Cosmos” observes J. C. Cirlot, “the central space is always reserved for the Creator, so that he appears as if surrounded by a circular or almond-shaped halo.”285

- Mithraic Saturn, with surrounding

- Japanese Buddha, with surrounding

If one accepts the immediate sense of the archaic terminology, the enclosure was no abstraction. It was Saturn ’s shining band. The Babylonian Anu—Saturn—was “the High One of the Enclosure of Life,” 286 his dwelling “the brilliant enclosure.” (Here, too, the enclosure becomes the place of the primeval “sunrise.”)287 The Maori of New Zealand know the planet Saturn as Parearau, whose name conveys the meaning “circlet” or “surrounding band.” From this name of Saturn, Stowell concluded that the natives could see the present Saturnian ring with the naked eye—something all astronomers know to be impossible today.288

When the African Dogon draw Saturn they depict it as an orb within a circle—a fact which Robert Temple, in his book The Sirius Mystery, cites as evidence for seemingly inexplicable Dogon astronomical knowledge (which he contends was introduced to the ancients by extra-terrestrial visitors!). But no one asks whether the order of the solar system may have changed, allowing for a once-visible Saturnian band.

The Lost Island

- Classical artists often portrayed the great god’s “halo” or “aura” as an arched mantle

For the primeval enclosure the Egyptians employed a variety of interrelated symbols. The circle of the khu or Aten was nothing other than the Island of Fire, the Province of Beginning. A single spell of the Coffin Texts thus identifies Re as “the noble one who is at the land of the Island of Fire,” but also calls Re the god “who is in his Aten.” 289 The subject is not two different enclosures but one enclosure under two different titles.

And this identification of the central sun as an enclosed or encircled god appears to throw light on the endlessly repeated myth of the lost island. What the Greeks called Ogygia (the island of Kronos/Saturn in the farthest north) occurs under many different names the world over. The white island, the floating island, the revolving island—may not these primeval dwellings simply echo the Saturnian enclosure? One recalls the words of Dionysius of Halicarnassus:

Haste to the realms [rings] of Saturn

shape your course,

Where Cotyle’s famed island wandering floats

On the broad surface of a sacred lake [the Abyss].290

Not of our earth, the lost isle floated in the sea of heaven. Japanese legends recall the ancient cradle of life as Onogora, a floating island (“the drifting land”) which congealed on the waters. This was the isle of the Congealed Drop. Its location, states a native commentator, was originally the North Pole, from which it eventually moved to its present position. 291 O’Neill properly relates the Japanese isle to the floating island of Delos raised from the sea by Poseidon. Another name for this island was Ortygia, which O’Neill connects with the Latin verto, Sanskrit vart, “to turn.”292 Answering to the same tradition are the Floating Islands of the Argonautica, called the Strophades, or “Islands of Turning.”

In the voyages of the Celtic divine hero Maelduin the adventurer encounters a fabulous isle in the midst of the sea: “Around the island was a fiery rampart, and it was ever wont to turn around and about it.”293

Examples are too numerous to receive elaborate treatment here: the primeval, revolving islands of Rhodes and Corcyra, spun on the cosmic spindle; the primeval isle of the Cyclos, “wheel,” which gave its name to the Cyclades; the “white island” of Zeus “in the midst of the sea”; the floating Hindu white island (Shweta-dwipa) at the polar centre; the lost Toltec “white island” of Tula, the centre of the world.294

Without exception, the shining, floating, revolving islands are esteemed as the place where history began and seem to answer to the same archaic tradition as the Egyptian Province of the Beginning, the revolving enclosure around the central sun. Is it possible that the ancients saw the mythical island—that the isle was not a geographical location, but a visible band enclosing Saturn? One must consider several closely related images, which also imply a visible band around the ancient sun-planet.

The Egg. A hymn from the Egyptian Coffin Texts reads:

I was he who came into existence as circle, he who was the dweller in his egg.

I was the one who began everything, the dweller in the primeval waters.295

Here the reference is to Atum as the creator of the egg, but other traditions say of the great god Ptah that he

“created the egg which proceeded from Nun [the cosmic waters].296

In the Book of the Dead the light god shines as “the mighty one within the egg.”297 “Homage to thee, O thou holy god who dwellest in thine egg.”298

As the stationary light god “turns round about” his egg revolves around him. “I am the god who keepeth opposition in equipoise as his Egg circleth round.”299 “O thou who circlest round, within thine Egg.”300 Atum, as governor of the revolving egg, is the lord of Time, for “time is regulated by the motion around the egg,” Clark tells us.301

Similar to the egg of Atum is the revolving sphere produced by the Orphic Chronos (Time, who is Kronos,

Saturn):

The great Chronos fashioned in the divine Aether [the fiery sea] a silver egg.

And it moved without slackening in a vast circle.302

To this revolving egg compares that of the Society Islands’ creator Ta’oroa, “the ancestor of all the gods,” who sat “in his shell in an egg revolving in endless space.”303

- Ptah, fashioning the World Egg upon a potters

The same egg appears in Hindu myth, set in motion by the central sun Prajapati.304 Mircea Eliade finds recollections of the cosmic egg in Indonesia, Iran, Phoenicia, Latvia. Estonia, West Africa, Central America, and the west coast of South America as well.305

Certainly, none of the later traditions improve upon the Egyptian texts which describe the egg as the enclosure round Atum-Re. But one can hardly fail to be impressed by the consistency of the tradition. And even the alchemists, much of whose teachings descended from Egypt, remember the connection of the egg with Saturn. They recall the egg as a fiery enclosure on the primordial sea—a circle with a “sun-point” in the centre (i.e., ). This “world-egg is the ancient Saturn,” they say.306

Is not this cosmic egg the band which the Egyptians called Aten? “O thou who art in thine egg, who shinest from thy Aten,” reads the Book of the Dead.307 Just as the Egyptian god-king is “the ruler of all that the Aten encircles,” so also is he “powerful in the egg” or “ruling in the egg.”308

In celebrating the primeval egg, the priests commemorated the island of beginnings. Budge summarizes the Egyptian tradition: “The first act of creation began with the formation out of the primeval watery mass of an egg, wherefrom issued the light of the day, i.e., Re.”309 Concerning the identity of this egg and the island or “Province of the Beginning,” the texts from the temple of Edfu remove all doubt: another name for the Province of the Beginning was “the Island of the Egg.”310 Egyptian sources thus suggest this equation:

Aten (enclosure of the central sun) = Cosmic Egg = Primeval Island

The Bond. To reside within the Aten is to reside “in the coil” or “in the cord.” The Hieroglyphs depict the Aten as a cosmic bond or knot, indicated by an enclosure of rope with the ends tied together (shen ). (Thus shen, “coil,” “bond,” may be written with the determinative , the Aten sign.) The bond signifies both a boundary—distinguishing the unified domain of the Universal Monarch from the rest of space—and order, marked by ceaseless, stable revolution round the central sun. It is the “bond of regularity” (shes maat), protecting the god-king from the surrounding waters of Chaos. Accordingly, the Egyptian king, considered as the incarnation of the Universal Monarch, takes up symbolic residence within the celestial cord, acquiring the great god’s power as “ruler of all that the Aten encircles.” The priests indicated this power of the terrestrial ruler by placing his hieroglyphic name within the shen-coil . And in order to accommodate longer names they eventually expanded the coil to an ovoid form, which yielded the familiar royal cartouche in which the names of all later kings were inscribed.

Of this cosmic bond or knot the hieroglyphics offer many signs (among them

). But each possesses the same root meaning as a protective boundary defining the original dwelling of the creator in heaven. The symbols convey the sense “to circumscribe,” “to set the bounds.” The creator, as the Measurer, prescribes the limits and measures out the sacred enclosure by “stretching the cord” round about, producing a unified dwelling (the primeval island), protected from the evils of Chaos and darkness.311

That the ancient mythmakers conceived Saturn’s enclosure as a cord binding together the god’s dwelling will explain why the Babylonian Ninurta, Saturn, holds the markasu or “bond” of the Cosmos. Langdon writes: “The word markasu, ‘band,’ ‘rope,’ is employed in Babylonian philosophy for the cosmic principle which unites all things, and is used also in the sense of ‘support,’ the divine power and law which hold the universe together.”312 The Orphic poet thus celebrates Saturn (Kronos) as “Father of the blessed gods as well as of man . . . you who hold the indestructible bond . . .”313

It is easy for contemporary writers to speak of Saturn’s bond as an invisible principle holding “the universe together,” but in the original symbolism one sees the bond as the shining boundary of Saturn’s dwelling (the true Cosmos). It was not in Egypt alone that the cord signified the “edge” or “border.” What the Greeks called peirata, “rope” or “bond,” possesses the additional meaning “boundary.” The Latin ora, “cord,” means also “edge.”314 A similar meaning attaches to the “noose” of the Hindu Varuna and Yama. The bond delimited and protected the sacred space occupied by the Universal Monarch, and its connection with the sign links it directly with Saturn’s island-egg.

The Garment. Mythmaking imagination also appears to have conceived the Saturnian band as the god’s girdle, collar, or belt. “I am the girdle of the garment of Nu, shining, shedding light,” states a hymn from the Egyptian Book of the Dead.315 The great god is “the Girdled and the Mighty one, coming forth triumphantly.”316 A common hieroglyphic determinative of the “girdle” or “collar” is the cord sign .

The Shield. All creation legends involve a struggle between the light god and the destructive powers of the Abyss (Chaos). The mythic enclosure provides the god’s defense against the turbulent waters which originally prevailed. The Egyptian enclosure, states Reymond, “had the function of protecting the sacred area from the evil coming from outside.”317 Aten was one of the numerous Egyptian names for this defensive rampart in heaven: “The Aten makes thy protection,” states the Litany of Re.318 The cosmic egg serves as the same fortress: “I am Horus . . . , whose protection was made within the egg; the fiery blast of your mouths [the fiery water of Chaos] does not attack me.”319

The band of the Aten , as the protective boundary, was the great god’s “shield,” fending off what the texts call “the fiends” of disorder. It is this mythic history of the band which explains why, in the hieroglyphs, the shield sign signified sacred space in general. All who resided within the shield’s enclosure occupied the safe and stable ground.

9. Mexican divinity holding a revolving cord-shield

Cord, belt, and shield converge. The great father wears the cord as a girdle: it protects him as a shield—not merely in Egyptian symbolism, but in the international language of symbols. Why, for example, did divine figures from Babylonia to Greece to Mexico wear a sacred belt of rope, and why was the belt conceived as an impenetrable defense? Mexican illustrations of the divine shield show it to be nothing more than a circle of rope. It was certainly not practical experience which suggested the magical powers of a shield so conceived! But the mythical imagery of the enclosed sun is quite sufficient to explain such anomalies: the great god’s shield and the celestial cord signified one and the same protective enclosure.

If the ancients actually saw a band around Saturn, it is clear that the enclosure fostered diverse but interrelated mythical interpretations. A literal reading of Egyptian and other texts will confirm an extraordinary equation:

enclosure of the central sun = primeval island = cosmic egg = cord (bond) = girdle (belt, collar) = shield

Concerning the overlapping images much more needs to be said. The signs and the myths become comprehensible only when one relates them to the heavens of ancient times. Celestial island, egg, cord, girdle, and shield mean nothing more than a shining, revolving enclosure around the great god. Was this band real or imaginary? The question can be answered by exploring certain other aspects of the enclosure.

The Cosmos And The Divine Assembly

The sign of the enclosed sun portrays a circle of secondary lights revolving about the stationary god and forming Saturn’s Cosmos. The mystic traditions of the great father present an apparent paradox: he is the god One, the solitary god in the cosmic sea; yet he is the All, embracing a company of lesser gods.

This is not a contradiction. In the first phase of creation the god brought forth a circle of secondary lights: these issued directly from the god to become his visible limbs. It is the fundamental character of the god One—the Heaven Man—to unite in a single “body” all the secondary powers of the Cosmos.

In Pythagorean, Neoplatonist, and Gnostic systems the primal figure is “the One, the All,” whose symbol is the enclosed sun . Hindu mysticism offers the latter sign as the image of the primordial unity, and the same interpretation is repeated by the alchemists.

Today one naturally thinks of “the All” as boundless space. The terms which translators render as Cosmos, heaven, firmament, sky, or universe suggest to the modern mind a limitless arena of the sun, moon, planets, and constellations. But the original meaning of the All is bounded space—a place (the place, or place par excellence). The Cosmos simply means the province of the god One, who, as Lord of the All, governs and is the “whole and its parts.” Having overlooked this restricted sense of the terminology the translators replace concrete meanings with ambiguity (in the guise of modern-sounding metaphysics). The once-visible dwelling of the central sun thus becomes, in the translations, “all existence.”

Almost without exception the translators fail to notice 1) that the creator was Saturn, recalled as the central sun; and 2) that the sign of the central sun and the sign of the All were the same image . The true Cosmos was Saturn’s enclosure. And nothing else is necessary in order for one to understand the ancient characterization of Saturn as the Heaven Man whose “body” encompassed the Cosmos. When Hildegard Lewy reports that the Sumero-Babylonian priests of Saturn regarded the planet-god as “the embodiment of the whole universe” the modern mind boggles: could the ancients have been so frivolous as to identify Saturn—the present, barely discernible point of light—with “the whole universe”? The answer is that Saturn was not a mere speck of light, but a gigantic globe at the polar centre; and the “universe” did not mean the open heavens but Saturn’s dwelling, the an-ki or band of the Cosmos. Saturn’s towering form “filled the an-ki.”

Zoroastrian texts describe the original Cosmos as the body of Zurvan (Time, Saturn), a revolving wheel called the Spihr, which remained ever in the same position. The fall of the stationary wheel coincided with the collapse of the primordial era.320 The image suggests, not unlimited “space,” but the tangible configuration of the enclosed sun .

Accordingly, the later mystic traditions, as reviewed by Jung, describe the image as the cosmic form of Adam, the Anthropos, the Original Man or Man on High—identified as Saturn.321 Always the “body” of this primal man means “Cosmos.”

The interrelated myths and symbols of Saturn’s Cosmos receive remarkable clarification in the creation accounts and the liturgies of ancient Egypt. Though I briefly touched on the Egyptian texts in earlier discussions of the Heaven Man, amplification is necessary.

The Circle of the Gods

Whether called Atum, Re, Osiris, Horus, Khepera, or Ptah, the Egyptian great god sits enthroned within a circle of secondary deities, satellites of the central sun. The gods are the Glorious Ones, Never-Resting Ones, or Living Ones; the Circle of Fire, Divine Chiefs, Apes of Dawn, Holy Ancestors, or Revolving Ones; the Followers of Horus, the Followers of Re, or the Followers of Osiris.

While the divine assembly possessed many names, its singular character stands out in the texts of all regions. There is no Egyptian company of the gods other than that which revolves round the central sun—a fact uniformly ignored by writers on Egyptian religion.

The texts repeatedly confirm the same relationship of the assembly to the great god: This is the Circle of gods about Re and about Osiris.322

The satellites of Re make their round.323 Thy followers circle about.324

Re maketh his appearance . . . with the cycle of gods about him.325 His Ennead [circle of gods] is around about his seat.326

I am Re amidst his Ennead.327

Go ye round about me, O ye gods.328

Hail to you, Tribunal . . . O you who surround me . . .329 Divine is your name in the middle of the gods.330 These gods shall revolve round about him.331

Glorious is your sah [brilliant form] in the midst of the living Ones.332

These are the “stars who surround Re.”333

When it is light all faces adore him, the Brilliant One, he who arises [shines] in the midst of his Ennead.334

The dilemma for solar mythology is obvious: seeing the references to the great god in the above lines, no one would think of denying that the subject is a visible power (which all presume to be our sun). But the descriptions of the god’s revolving companions are equally explicit. To what visible powers do they answer? No circle of lights appears to revolve about the body we call sun today.

Egyptian descriptions of the celestial assembly take us back to the remote age, separated from the present by a wide chasm. Every Egyptian cult possessed mythical accounts relating to the birth of the divine assembly in remote times. Despite numerous versions of the legend, it is impossible to ignore the coherent pattern. From a study of the numerous fragments, I offer the following reconstruction and interpretation of the myth.

In the primordial epoch the creator first appeared in the Abyss, alone, wandering, without a resting place. “I found no place to stand—I was alone,” states the god.335

After his appearance the god “uttered words” and these utterances possessed a visible form as the kheperu, the first things created. The kheperu “came forth from my mouth.”336 These visible “words” flowed from the creator as the waters of Chaos, the sea in heaven upon which the creator floated or wandered. To reckon with the tradition in its own terms one must think of the primordial sea as a fiery “ocean of words” in heaven, emitted by the god in a prolonged and resounding explosion.

An Egyptian term virtually identical to kheperu is pautti, often translated as “primeval matter.” The pautti issued directly from the creator in the form of radiant speech, forming a fiery, watery mass. The creator brought forth this primeval matter and, paradoxically, “produced himself” in it (“I produced myself from the primeval matter which I made”).337

For a time the creator wandered in the luminous sea but eventually came to rest at a point of stability, the cosmic centre. Two events followed: an island congealed around the god as his “place of rest,” and the circle of the gods came into being, embracing the creator. The two events are synonymous.

From the unorganized sea of words the kheperu or pautti the creator brought forth an organized dwelling. He “gathered” the enclosure together as a barrier against the watery Chaos which he himself had created. The fiery particles of the newly formed enclosure composed the circle of the gods. That is, the gods stood on the enclosure’s “edge” or “border”—the “shore” of the celestial isle . In one text these are “the gods who belong to the Shore. They give an island to the Osiris NN.”338 This was the Cosmos, formed by the “Council of the gods who surround the Island of Fire.”339

Vital to this interpretation of the myth is the identity of the divine assembly with the kheperu or pautti “uttered” by the creator. The secondary gods are themselves the shining “words” or “names” spoken by the creator and organized into a revolving

circle. Kheperu thus means “the revolving ones,” while pautti signifies “the primeval ones,” who inhabit and give form to the Island of Fire.340

What, then, do the texts mean when they say that the kheperu or pautti, though erupting from the creator, “produced” the great god? The answer is clear-cut: the circle into which the constituent particles (visible words) congealed was the creator’s “body.” The god One “collected” or “gathered together” his own limbs (“I united my members”). He “produced himself.”341

The Coffin Texts depict the creator alone in the primeval sea:

[I was] he who had no companion when [or until] my name came into existence . . .

I created my limbs in my “glory”

I was the maker of myself . . .342

Literally, the limbs which the god produced are “my limbs of my khu.” The phrase is of sweeping significance. An Egyptian sign of the khu was the hieroglyph . The term, in explicit reference to the creator’s “circle of glory” (halo, aura, Aten), means at once “words of power” and “brilliant lights.” Depicted by the hieroglyph is the island of creation, around which are ranged the secondary deities (khu) produced through the creator’s “speech.” In bringing forth this divine assembly the creator became the maker of his own body. “O Khepera . . . whose body is the cycle of the gods forever,” proclaims the Book of the Dead.343 The same texts speak of “the souls of the gods who have come into being in [or as] the members of Osiris.”344

The entire symbolism focuses on the celestial form of the enclosed sun . Individually, the fiery lights which compose the enclosure (island of the Cosmos) are the creator’s “limbs” (plural), but as a unified circle, the assembly forms his “body” (singular). Correspondingly, the respective lights are the creator’s multiple “names” or “words” (“the names of his limbs”), while as an organic whole (the All) the circle is the god’s singular “Name.” When the hymn cited above states that the god was alone “until my name came into existence,” the meaning is concrete, not abstract. The creator remained alone until he brought forth the circle of the khu, his visible Name in heaven.

That the god’s Name was his tangible dwelling—his circle of glory—is a fact absolutely essential to a comprehension of the enigmatic symbolism. “I have made firm my name, and have preserved it that I may have life through it.”345 The reference is to the enclosure of life, the Island of Fire “made firm” at the stationary cosmic centre, when the creator ceased to wander in the Abyss. Thus the hieroglyphic determinative of “name” (ren) is the shen sign , the sign of the celestial enclosure or circle of the Aten. To possess a “name” is to reside within the Aten . A single hymn from the Book of the Dead provides a remarkable summary of the related symbols:

I am the great god who came into existence by himself. This is Nu who created his names paut neteru as god.

Who, then is this?

It is Re, who created the names of his limbs. There came into existence in the form of the gods who are in the following of Re . . .

Who, then, is this?

It is Tem [Atum] in his Aten.346

The self-generated god in the above lines is Nu, whose hieroglyph identifies him as both the source and the substance of the cosmic waters. The text says not only that the great god “created his names” but that these “names” are the paut neteru—the circle of the gods.

But why is the assembly called the paut, or primeval matter? It is because the revolving gods erupted directly from the creator, eventually forming the organized enclosure. The secondary gods, as words or names spoken by the creator, composed the god’s own “limbs,” so that the text can say the god “created the names of his limbs.” That these “came into existence in the form of the gods who are in the following of Re” means simply that they formed the revolving assembly.

Who, then, is this god who shines within the circle of his own limbs? “It is Atum in his Aten.” The priests could not have stated more emphatically the equation of the celestial assembly and enclosure of the primeval sun . Here is the formula set forth by the Egyptian texts:

Cosmos (enclosure of the central sun) = primeval matter (sea of words) in its organized form = circle of the gods = limbs or body of creator = creator’s visible Name

That the circle formed by the divine assembly is the cosmic dwelling of the creator is a truth affirmed not by one local cult alone, but by all streams of Egyptian ritual. Below I list a few of the Egyptian words that connect the assembly with the enclosure of the central sun:

Khu. In the creation, as noted above, the khu erupt from the creator as “words of power” or “brilliant lights.” This “circle of glory”

the body of Osiris or Re composes the god’s celestial home, the Aten . Thus khus means “to fashion a dwelling.”

- The body of Osiris forming the circle of the Tuat, the

Tuat. The term refers to the “resting place” of the creator at the summit. The hieroglyphic symbol of the Tuat shows the light god within a celestial band which the texts equate with the circle of the Aten, “The Mysterious Soul, which rests in its Aten, rests in the Tuat of Re.”347 In the hymns and in art, the Egyptians depicted the Tuat as the body of Osiris or Re. But Tuat means also “the circle of the gods”; the enclosure, the “body” of the sun-god and the divine assembly are synonymous.

Shen, shenit, sheniu, shenbet. The shen signs and portray the central sun’s enclosure as a cord of rope—the bond of the Cosmos. Shen means “to revolve,” in reference to the revolving band of the Aten. (The shen sign and the Aten sign function as interchangeable glyphs.) Hence, the sheniu is the great god’s cosmic “chamber” while the shenit are the “chiefs” or “nobles” on high who travel the circuit round the shen. Shenbet, meaning “body,” is the bet or “place” marked out by the shen. Again, enclosure, “body,” and assembly converge. Tchatchat. The tchatchat are the “chiefs” or “heads”—the council of gods revolving around the stationary sun. But tchatchat also signifies boundary,” “enclosure,” or “holy domain.” The circuit traversed by the chiefs is the boundary of the celestial enclosure .

Rer, reri, rert. While rer means “to revolve or encircle,” rert means “men”—the inhabitants of the primordial domain. The reri are “the revolving ones” (comparable to the kheperu), who collectively enclose the sacred space. Accordingly, rer possesses the additional meaning “the enclosed domain.”

Paut, pat. The secondary gods are the pautti, the “primeval matter” which (as stated above) congealed into the creator’s revolving dwelling. Paut thus signifies the creator’s “body.” Obviously related are the pat, the primeval gods whose name conveys the sense “to go round like a wheel or in a circle.” It is no coincidence that the hieroglyphic determinative of the pat is an egg : the circle around which the pat revolve is the egg of the Cosmos, and this egg is the “body” of the god Seb.

Tchet, tchet, tchetu. While tchet means “to speak,” tchetu signifies “words,” “things spoken.” In the creation the great god uttered visible “words” in the form of the lesser gods. That the creator’s words became his dwelling is reflected in the term tchet, the “house” or “chamber” of the great god. Tchet also means “body.”

Shes, shesi. An Egyptian name of the cosmic bond is shes, written with the hieroglyph . The Tuat ( , dwelling of Re or Osiris) is the shes maat, the “bond of regularity” (or of stable, ceaseless revolution). The texts also speak of celestial shesi, divine “warriors” who protect the great god. They “protect” the god because, collectively, they form the defensive rampart, the cosmic shield.

The language and symbolism of the celestial assembly reveal an underlying idea connecting the separate traditions. The secondary gods are not merely ill-defined “companions,” or “assistants” (as so many Egyptologists seem to assume); rather, they possess concrete form as the enclosure of life, the very enclosure which the priests celebrate as the island of beginnings, the revolving bond, or the cosmic egg (all figures of the Cosmos).

The Cosmos, in other words, has nothing to do with “all existence.” The concept relates to an organized domain—“the whole and its parts”—fashioned by the creator out of previously unorganized cosmic debris (primeval matter). An Egyptian word for the unified domain is temt, which means “all” or “complete” and also “to collect,” “to gather together.” Clearly related is the word Temtiu, one of the names of the secondary gods. It is the secondary gods themselves that the creator “collects” or “gathers together” to form the cosmic island.

Pertaining to the same root concept are the terms tema, “to unify, join together”; temi, “shore,” “bank,” or “border”; and temen, “all,” “totality.” The unified All (Cosmos) is contained within the border of the enclosure, and the border is the shore of the cosmic island .

The Saturnian band is thus the pathway traversed by the secondary gods. The gods revolve around the shore, or around the bond, or around the egg. “Every god who is on the border of your enclosure is on the path . . . ,” states a Coffin Text.348

The testimony could not be more explicit. The road traveled by the secondary gods is the uat, the “way” or “path,” denoted by the glyph . But the same glyph signifies the tcher, “boundary.” The path of the gods and the boundary of the unified Cosmos (the All) are synonymous. Thus the phrase er tcher (“to the tcher” or “to the boundary”) means “all,” “the whole.” The great god, as Neb-er-tcher”—he who rules to the boundary”—is the ruler of the whole, lord of the revolving Cosmos. It is the same thing to say that he governs “all that the Aten ] encircles.” The whole range of images challenges orthodox interpretations.

But the symbolism of the Cosmos and divine assembly reaches far beyond Egypt. Do not all supreme gods sit enthroned within the circle of secondary divinities? Ninurta, Kronos, El, Yama, Huang-ti and every other Saturnian figure has his “sons,” “councilors,” “spies,” “followers,” “assistants,” or “warriors” seated round about him. The Mesopotamian sign is a self-evident image of the celestial assembly. It is this Cosmos—not boundless space— which Saturn’s “body” encompassed. What the mystics knew as “the universe” organized within Saturn’s “bond” or “cord” (Babylonian markasu) becomes meaningful only as the visible Saturnian band, or circle of the gods.349

The Great Mother

The sign of the enclosed sun also portrays Saturn, the generative Seed, within the womb of the mother goddess. As the female personification of the Cosmos, the great mother is inseparable from Saturn’s “body.”

The mysteries of the mother goddess give rise to an endless debate. What is the fact in nature which will explain the cosmic union of Isis and Osiris, Tammuz and Ishtar or Kronos and Gaea? One scholar after another puzzles over the goddess’ varied forms, finding her everywhere and nowhere. If to one writer she is the fertile earth around us, to another she is the moon and to another “the universe,” the “sky,” or the morning star. The diverse interpretations seem to suggest that there were many goddesses with a singular figure—the heavenly consort of the great father. Here, for example, is one statement, offered as the words of the Egyptian goddess Isis to Apuleius:

. . . My name, my divinity is adored throughout the world, in divers manners, in variable customs, and by many names. For the Phrygians that are the first of all men call me the Mother of the gods of Pessinus; the Athenians, which are sprung from their own soil, Cecropian Minerva; the Cyprians, which are girt about by the sea, Paphian Venus; the Cretans, which bear arrows, Dictynian Diana; the Sicilians, which speak three tongues, infernal Prosperpine; the Elusinians, their ancient goddess Ceres; some Juno, others Bellona, others Hecate, others Ramnusie . . . ; and the Egyptians, which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustomed to worship me, do call me by my true name, Queen Isis.350

In their cosmic rites the Egyptians seemed unwilling to distinguish Isis from such local figures of the great mother as Nut, Hathor, Mut, or Neith. Each local goddess bore identical or similar epithets (the Eye of Re,” “the mother of Re,” “the Lady of the Holy Land,” etc.).

But if the ancients acknowledged a common personality of the goddess, what was that personality’s underlying trait? There is one universal attribute: the great goddess possesses the form of an enclosure—a circle or womb—housing and “giving birth to” the great father. Neumann perceived this trait when he described the goddess’ “elementary character” as “the Great Round” or “the world-containing and world-creating uterus.”351 From his exhaustive study of the great mother G. S. Faber concluded that every goddess appears as a protective enclosure sheltering the great father. Of this truth there is no shortage of evidence.352

The god Tammuz sits within the womb of Tiamat, “the mother of the hollow.” “Mother-womb” is the epithet of the Sumerian goddess Gula, while Ishtar’s name means “womb.”353 Hindu sources describe the great mother as the yoni or “womb” and the great father as “he enveloped in his Mother’s Womb.”354 Agni is the male god “shining in the Mother’s eternal womb.”355

Similarly, the Norse Odin is “the dweller in Frigg’s bosom.”356 In Orphic doctrine the receptacle housing the great father is the goddess Vesta. The Gnostics remembered the old god as the “Ancient of Days who dwelt as a babe within the womb.”357 Among the Maori the great mother is the “Shelter Maid” or “Haven Maid.”358

Descriptions of the primeval womb show that the ancients recall the goddess as a visible band—what Hindu texts call the “golden womb,”359 and Babylonian “the jeweled circlet (a title of Ishtar).360 The imagery pertains directly to the enclosed sun . In Hinduism the latter sign depicts “the male seed-point or bindu in the cosmic womb,” states Alan Watts.361 “The Father is like the centre (Nabhi) of the circle and the Mother the circumference (Paramanta),” notes Agrawala.362 The same male-female symbolism of the enclosed sun occurs in European stone carvings discussed by V. C. C. Collum.363 That the Hebrews regarded the Shekinah (the creator’s encircling “aura,” “anima,” or “glory”) as “the Mother”364 leads to the same conclusion: the great god’s halo was his own spouse. Accordingly, the Tibetan ritual invokes the great god as “the centre of the Circle, enhaloed in radiance, embraced by the (divine) Mother.”365

This conception of the great mother receives compelling support from ancient Egyptian sources. The Egyptian sun-god has his home within the womb of his mother and consort, the “Great Protectress.”366 Of Re, the Book of the Dead proclaims, “Thou shinest, thou makest light in thy mother.”367 Elsewhere Re appears as the sun “in the womb of Hathor.”368

Osiris shines forth from the enclosure of his mother Nut: “Homage to thee, King of kings, Lord of lords, Prince of princes, who from the womb of Nut hath ruled all the world.”369 The abode of Horus is his mother Hathor, whose name means “the House of Horus.” And the goddess Nekhebet is said to personify the primeval abode of the sun.370

As earlier noted, the Egyptians portrayed the celestial dwelling as the shen bond . But this enclosure was really the womb of Nut, states Piankoff.371 (Thus the goddess Shentit takes her name from the shen bond.)

The mother goddess was not our earth, not the open sky, not the moon, but the dwelling of the central sun, the enclosure of the Aten : “My Aten has given me birth,” states the god-king.372 This direct connection of the mother goddess with the sun’s enclosure will explain why the Aten sign , though serving as the glyph of Re, also denotes “mistress,” in reference to the god’s celestial consort.373 The god’s mistress was his own emanation, his halo of “glory” or “splendour.” The priests who invoked the great god’s khut or “circle of glory” also celebrated the goddess Khut, who was the same circle.

Residing within the enclosure, the central sun is the shining seed impregnating the great mother. “I am indeed the Great Seed,” declares Re.374 “O Re, make the womb of Nut pregnant with the seed of the spirit which is in her,” reads a hymn of the Pyramid Texts.375 The same texts celebrate “the womb of the sky with the power of the seed of the god which is in it.” 376 And again, “Pressure is in your womb, O Nut, through the seed of the god which is in you.”377

In his coming forth within the cosmic womb the sun “copulates with” or “impregnates” the mother goddess, and this relationship expresses itself in the language. The Egyptian nehep means “to copulate” while nehepu means “to shine.” Though beka denotes “the coming forth” of the sun, the same word means “pregnant.” Thus the union of the primal pair is renewed daily (or with each “dawn” of the central sun).

But the same coming forth receives mythical interpretation as the birth of the light god. Nut is at once Re’s spouse and his mother, who “bears Re daily”:378

I am exalted like that venerable god, the Lord of the Great House, and the gods rejoice at seeing his beautiful comings forth from the womb of Nut.379

His birth is wonderful, raising up his beautiful form in the womb of Nut.380

Hail, Prince, who comest forth from the womb.381

Conception and birth are thus confused. The impregnating Seed (father) is also the Child. It is this equation which yields Re’s title as “Man-Child.”382 He is the prototype of “the son who impregnates his mother,” or the “father who gives birth to himself.”

But the confusion does not end here, for the mother goddess, as the great father’s encircling aura, is herself the emanation of the masculine power. The solitary god brings forth the womb of heaven unassisted. In this sense the goddess is the great father’s “daughter,” so that if one considers the entire range of possibilities, three relationships to the goddess—father, husband, and son—are united in one figure.

Imagery of this sort runs through all of the religious texts of ancient Egypt. Amon-Re is “he who begets his father.”383 The goddess Hathor becomes “the mother of her father and the daughter of her son.”384 Atum-Kheprer “brought himself into being upon the thigh of his divine mother.”385 In the ritual of the Karnak temple Re’s “daughter” Mut encircled “her father Re and gave birth to him as Khonsu.”386 The same goddess is “the daughter and mother who made her sire.”387

Equation of father and son is explicit in the case of Osiris and his “son” Horus. The Pyramid Texts describe Osiris shining “in the sky as Horus from the womb of the sky.”388 “The king is your seed, O Osiris, you being potent in your name of Horus who is in the sea.”389 The gods, in the Book of the Dead, recall the ancient time of Horus “when he existed in the form of his own child.”390

Because the terrestrial king symbolically acquires the attributes of the Universal Monarch, the rites show the local ruler uniting with the mother goddess and reproducing himself within the cosmic womb. He announces that he has been “fashioned in the womb” of the great mother,391 and after invoking “the womb of the sky with the power of the seed of the spirit which is in it,” then proclaims: “Behold me, I am the seed of the spirit which is in her.” 392 “O Nut . . . it is I who am the seed of the god which is in you.”393

Frankfort deals with the subject at length, showing that the king’s impregnation of the mother goddess and simultaneous birth in the womb was central to Egyptian ritual. The king “enters her, impregnates her, and thus is borne again by her” 394 exactly as the great god himself.

If the king receives his authority on earth through personification of the Universal Monarch, it is through the same identification that he attains the heavenly abode of the goddess upon death, taking up his residence within the sheltering womb as an Imperishable One. In a hymn to Nut, King Pepi beseeches the goddess, “Mayest thou put this Pepi into thyself as an imperishable star.”395 “Mayest thou transfigure this Pepi within thee that he may not die.”396

Frankfort comments: “ . . . the notion of a god who begets himself on his own mother became in Egypt a theological figure of thought expressing immortality. The god who is immortal because he can re-create himself is called Kamutef, ‘bull of his mother.’”397 The king aspires to duplicate the feat of the Universal Monarch, giving birth to himself in the womb of Nut. Though the divine marriage and its imitation in kingship ritual involve many complexities and enigmas, the underlying theme remains clearly defined. Symbolically, the king has his home in the cosmic womb; he simultaneously impregnates the goddess and is “born” by her. The source of the ritual is celestial, for it reenacts the First Occasion when the great father, the fiery Seed, took to wife the band of “glory” which congealed around him. The sign of the primordial union is everywhere before us but rarely recognized. It is the sign of the enclosed sun .

Womb and Thigh

In connection with the symbolism of the mother goddess one notes that the “womb” is generally synonymous with the “thigh” or “lap.” When ancient relieves depict the god or king on the lap of the great mother, they refer to the primeval union, in which the father of the gods resides within the goddess’ protective enclosure.

An Assyrian tribute to Assurbanipal reads: “A meek babe art thou, Assurbanipal, whose seat is on the lap of the Queen of Ninevah [Ishtar].”398 Thus the Sanskrit yoni, the female enclosure and dwelling of the great father, may be translated either “lap” or “womb.” The Latin word for “thigh”—femen, feminis—means “that which engenders.”399 A similar connection occurs in Egypt, where Khepesh, “thigh,” means the womb of Nut housing Osiris or Re.

Many gods—in Hindu, Greek, and European myth—are thus “born from the thigh,” like the Egyptian Kheprer who “brought himself into being upon the thigh of the divine mother.”400

This overlapping symbolism of womb, lap, and thigh will be met more than once in the following sections.

Womb and Cosmos

To identify the mother goddess as the band of the enclosed sun is to equate the goddess with Saturn’s Cosmos, the revolving company of the gods. The goddess Nut is “the representation of the cosmos,” states Piankoff.401 Thus while the Egyptian khut signifies the “circle of glory” formed by the secondary gods, Khut also means the mother goddess. And though the shenit are the “princes” in the divine circle, the goddess is Shentit; both words derive from the shen, the bond of the Cosmos.

- The Man-Child on the lap of the mother goddess

The religious texts confirm the equation. “He is the one who cometh forth this day from the primeval womb of them [the secondary gods] who were before Re,” reads the Book of the Dead.402 “I have come forth between the thighs of the company of the gods.”403 What the Book of the Dead calls “divine beings of the Thigh”404 means the celestial assembly, the secondary gods who collectively form the womb of cosmic genesis.

But the interrelated symbolism does not stop here. Every Egyptian priest knew that the mother goddess was the revolving egg housing the central sun. Indeed, the hieroglyphic image of an egg at the end of the divine name means “goddess.” Of Osiris the goddess Isis declares: “His seed is within my womb, I have molded the shape of the god within the egg as my son who is at the head of the Ennead.”405 The god within the womb is the god within the egg, who is the god ruling the Ennead (circle of gods).

By the same equation the womb becomes the garment or belt girdling the sun: the deceased king prays that he may be girt by the goddess Tait,406 or announces that “My kilt which is on me is Hathor.”407 In the case of the goddess Neith the womb becomes the shield. (The shield is the hieroglyph for Neith.)408 Though the symbols of the primeval enclosure differ, each is presented as a form of the great mother, whose entire character answers to the visible Saturnian band .

The Hermaphrodite

In the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris, dated around the first half of the fourth century A.D., appears the Oracle of Kronos. The recommended prayer invokes Kronos as “Lord of the World, First Father,” but also bestows on the god the peculiar title “Man-Woman.”409 Kronos is Saturn, the primeval sun. To what aspect of the god did this title refer?

In Saturn the primal male and female principles unite, yielding the hermaphrodite, or androgyne. Few of the preeminent deities of antiquity are free of this duality. The Sumerian Anu, Ninurta, Tammuz, and Enki; the Hebrew El; the Hindu Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva; the Iranian Zurvan; the Mexican Quetzalcoatl—all reveal a female dimension. Their spouse is never wholly separated from their own body.

The Egyptians esteemed Atum as “that great He-She,”410 while celebrating Amen as the “Glorious Mother of gods and men.”411 The Egyptian word for this primeval unity is Mut-tef, or “Mother-Father.” From what has been established in the previous pages concerning the symbolism of the enclosed sun there can be little doubt as to the concrete meaning of the Mut-tef. The word signified the organized Cosmos,412 the central sun and its enclosure, considered as the male and female parents united in a single personality: the great father’s body was also the god’s spouse, the womb of heaven.

This duality finds expression in the Egyptian term khat, which may be translated either “body” or “womb.” The man-child Horus, who dwells in the womb of Hathor, is Khenti-Khati, at once “the dweller in the body” and “the dweller in the womb.” The Litany of Re proclaims that “the khat [body] of Re is the great Nut,” the mother goddess.413

Egyptian artists showed the body of Osiris forming the circle of the Tuat, the abode of Osiris or Re.414 But every student of Egyptian religion knows that the Tuat, house of rest, was the womb of Nut.

The hermaphrodite, then, personifies the original Cosmos, which means Saturn and his visible dwelling . G.

- Faber, in his comprehensive study of ancient ritual, notes that the great father (“the Intelligent Being”) “was sometimes esteemed the animating Soul and sometimes the husband of the Universe, while the Universe was sometimes reckoned the body and sometimes the wife of the Intelligent Being: and, as the one theory supposed a union as perfect as that of the soul and body in one man, so the other produced a similar union by blending together the husband and wife into one hermaphrodite.”415

With Faber’s assessment it is impossible to disagree, so long as one remembers that to the ancients, the “universe” (Cosmos) meant Saturn’s home, not a boundless expanse. That Saturn’s Cosmos acquired a dual character as the god’s “body” and as his “spouse” is sufficient to explain the primordial Father-Mother.

The hermaphrodite or androgyne, Eliade tells us, is “the distinguishing sign of the original totality [i.e., the All].” Its customary form is “spherical,” he notes.416 We thus arrive at the following equation: