David

Wal

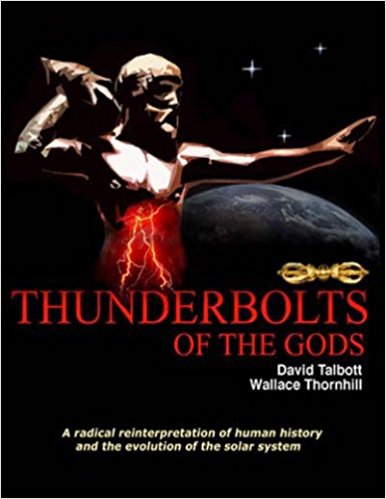

THUNDERBOLTS

OF THE GODS

Da vid Talbott and Wallace Thornhill

Mikamar Publishing

Portland, Oregon

To the scientists and historians of the future

Thunderbolts of the Gods

Copyright © 2004

David Talbott and Wallace Thornhill

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Thunderbolts of the Gods / by David Talbott and Wallace Thornhill

- Plasma and electricity in space 2. Plasma phenomena in ancient times

- Origins of mythology and symbolism 4. The cosmic thunderbolt ISBN xx xxxx xxxxxx

Printed in the United States of America by

Mikamar Publishing

1616 NW 143rd

Portland, Oregon 97229

503-645-4360

“It is the thunderbolt that steers the universe!”

Heraclitus, fifth century B.C.

INTRODUCTION

On a spiral arm of a galaxy called the Milky Way, nine planets move in peaceful, clock-like procession around a yellow dwarf star called the Sun. The planets move on highly predictable paths, and by all appearances nothing has changed in a billion years. The inhabitants of the third planet, the Earth, can see five of their celes- tial neighbors without the aid of telescopes. Surrounded by the background stars, these objects do little to distinguish themselves in the night sky. And few of us today have learned to identify the five visible planets against the starry dome.

Earlier cultures were not so complacent about the planets. They invoked these bodies with fear and reverence. In ancient Mesopota- mia, astronomer-priests insisted that the planets determined the fate of the world. In their prayers to the planets they summoned memo- ries of heaven-shattering catastrophe. What was it about these celestial objects that inspired this cultural anxiety? And why did so many ancient accounts insist that the movements of the planets once changed? That was Plato’s message more than 2300 years ago. The Babylonian chronicler Berossus said it too: the planets now move on different courses. But these are only two of the more familiar voices amidst a chorus of ancient witnesses.

In archaic texts the planetary gods were a quarrelsome lot. They were giants in the sky, wielding weapons of thunder, fire, and stone. Their wars not only disturbed the heavens but threatened to destroy the earth. Driven by reverence and fear, ancient cultures from Mesopotamia to China, from the Mediterranean to the Americas, honored the planets with pomp and zeal, seeking to placate these celestial powers through human sacrifice. The best English word for this cultural response is obsession.

From the Sun outward, the nine planets of our solar system are Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupi- ter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. Astronomers believe that the order of the planets has remained unchanged over the eons. But this uniquely modern belief rests on assumptions about gravity that predate the discovery of electricity and the arrival of the space age.

The authors of this book have each spent more than thirty years investigating the ancient message, and this has led us to question a pillar of theoretical science today—the "uneventful solar system." Following quite different research paths, we arrived at the same conclusion: the ancient sky was alive with activity. The evidence suggests that only a few thousand years ago planets moved close to the earth, producing electrical phenomena of intense beauty and terror. Ancient sky worshippers witnessed these celestial wonders, and far-flung cultures recorded the events in the great myths, sym- bols, and ritual practices of antiquity.

A costly misunderstanding of planetary history must now be corrected. The misunderstanding arose from fundamental errors within the field of cosmology, the "queen" of the theoretical sci- ences. Mainstream cosmologists, whether trained as physicists, mathematicians, or astronomers, consider gravity to be the control- ling force in the heavens. From this assumption arose the doctrine of eons-long solar system stability—the belief that under the rule of gravity the nine planets have moved on their present courses since the birth of the solar system. Seen from this vantage point, the ancient fear of the planets can only appear ludicrous.

We challenge this modern belief. We contend that humans once saw planets suspended as huge spheres in the heavens. Immersed in the charged particles of a dense plasma, celestial bodies "spoke" electrically and plasma discharge produced heaven-spanning for- mations above the terrestrial witnesses. In the imagination of the ancient myth-makers, the planets were alive: they were the gods, the ruling powers of the sky—awe inspiring, often capricious, and at times wildly destructive.

Cosmic lightning evolved violently from one discharge configu- ration to another, following patterns observed in high-energy plasma experiments and only recently revealed in deep space as well. Around the world, our ancestors remembered these discharge configurations in apocalyptic terms. They called them the "thunder- bolts of the gods."

PART I

THE COSMIC THUNDERBOLT IN MYTH AND SCIENCE

- Chapter One: Convergence

- Chapter Two: Mysteries of the Cosmic Thunderbolt

- Chapter Three: Electrical Encounters in Space

Recovering the lost messages of world mythology. . .

"Perseus Releases Andromeda," painting by Joachim Wiewael, 1630. When king Cepheus offended Poseidon, the god sent a flood and a sea monster to devastate the land. Cepheus hoped to appease the dragon by sacrificing his daughter. But Perseus, riding the winged horse Pegasus, defeated

the monster, winning the king’s permission to wed Andromeda.

Beautiful princess, chaos dragon, warrior-hero, and lost kingdom: the themes are commonplace in world mythology. But the historic roots of the themes continue to elude the experts who study them.

. . .with new tools and perspectives in the sciences

Beginning many centuries ago, a rebellion against traditional myth and magic led to the emer- gence of the scientific method. Experiment and sys- tematic observation of nature replaced belief in the gods of antiquity, leading eventually to an explosion of space age discovery. Yet today many scientists

are re-examining mythology, wondering if ancient stories of disaster have a scientific explanation. Could the mythic “dragon’s assault,” for example, refer to a natural catastrophe affecting the entire earth? The answer to such questions will come from the surprising role of electricity in space.

The Roman warrior Mithras (Persian Mithra) emerges from the cosmic egg, carrying a lightning bolt in his right hand and a staff in his left. Around his body entwines the cosmic serpent, a prototype of the mythic dragon.

I. CONVERGENCE

The Lens of Human Perception

When we gaze up at the stars, do we believe what we see, or see what we believe? Our beliefs and assumptions are like eyeglasses: they can help us see more clearly, but they can also limit our field of view.

Today, most astronomers assure us that the solar system is both

stable and predictable. But new vistas in the sciences often expose flaws in notions that once seemed obvious. Only a few decades ago, all well-trained, feet-on-the-ground scientists “knew” that—

- Space is empty and cannot conduct electricity;

- Magnetic fields do not exist in space;

- The tails of comets are pushed away from the Sun by the pres- sure of light;

- Jupiter and Saturn have been cold and inactive since the early history of the solar system;

- The planet Mars has been geologically dead for more than a billion years;

- Venus is our "sister planet," with temperatures close to those of the Earth;

- There are no other galaxies outside our own;

- There is no evidence for planet-wide geological disturbances of the Earth in the past.

Before new findings disproved these beliefs, they were so "obviously true" as to discourage challenges. It is easy to confuse theoretical assumption with fact. And today the tendency often conceals a tacit belief that, despite the mis- takes of previous generations, we have the big picture right and the remaining task is simply to tidy things up a bit.

The actual situation in the sciences calls for openness to new possibilities. Our vision of the universe is changing more rapidly than ever before, as space exploration fuels an explosion of

discovery. Before the advent of the space age, we could view the universe only in the few wavelengths of visible light seen from the surface of the Earth. Now we have expanded our vision into the ultraviolet, x-ray, and gamma-ray in the short wavelengths of the

The monstrous Tarantula Nebula, named for its many spidery fila- ments, is one of innumerable point- ers to magnetic fields in space, the result of electric currents.

New Lenses

for Viewing the Universe

telescopes are many times more powerful than Galileo's, and we have added instruments that detect the cosmos in wavelengths

Galileo's telescope could see eight times better than the unaided eye. It was strong enough to see four of the moons of Jupiter and the phases of Venus, but not the rings of Sat- urn. Yet the new data Galileo col- lected in his first few weeks of telescopic observations, com- bined with his powerful insight,

overthrew the Ptolemaic view of the

Galileo’s Telescope

our eyes cannot see—radio,

microwave, infrared, ultraviolet, x-ray, and gamma-ray. Also, for the first time in human history, we can see both the Earth and the universe from viewpoints no longer confined to the surface of the Earth.

Today, we have enormous tele- scopes on the ground and tele- scopes riding high-altitude balloons. We have telescopes in

orbit: around Earth, Mars, and Jupi-

universe—a view accepted for more than a thou-

sand years.

In the past 50 years, the observing power of astronomical instruments has expanded to levels inconceivable in the sixteenth century. Our optical

ter—even around a point in space where gravity between Earth and Sun is in balance. The recent flood of data from space not only sheds new light on traditional views of the universe, but introduces fundamentally new possibilities as well.

ABOVE, left to right: 100-meter radio telescope at Green Bank, West Virginia; launch of the microwave balloon TIGER; Jupiter probe from the Galileo mission to Jupiter and its moons. BELOW: Hubble Telescope, revealing com-

plex structures in remote space. Chandra x-ray telescope, capturing high-energy stellar and galactic systems; SOHO telescope, observing the Sun from an equilibrium position between the Earth and the Sun.

electromagnetic spectrum and into infrared, microwave, and radio in the long wavelengths. We can view at close range the surfaces of planets, moons, asteroids and comets. We can even touch and chemically "taste" them.

The new discoveries accent the unexpected—a sign that some- thing is wrong at the level of first assumptions. In fact, two of the most far-reaching discoveries of the past century came as great sur- prises: the pervasive role of charged particles in the universe; and the signature of planetary catastrophe throughout our solar system. The "big picture" of space has changed.

For centuries astronomers assumed that gravity is the only force that can give birth to stars and planets or can direct the motions of celestial bodies. They assumed that all bodies in the universe are electrically neutral, comprised of equal numbers of negative and positive particles. With this assumption astronomers were able to ignore the extremely powerful electric force. It was a fatal mistake. From the smallest particle to the largest galactic formation, a web of electrical circuitry connects and unifies all of nature, organizing galaxies, energizing stars, giving birth to planets and, on our own world, controlling weather and animating biological organisms. There are no isolated islands in an "electric universe."

The medium for this more “holistic” view of the universe is plasma, a highly conductive state of matter, distinguished by the presence of freely moving charged particles. We now know that plasma fills all of space—a fact unknown to the pioneers of gravita- tional theory. Except for the Earth and a few rocky planets, moons, and wandering solid objects, most bodies in space are composed of plasma. Moreover, a crescendo of evidence reviewed in this volume (and those to follow) makes clear that distant stars, our Sun, and the planets are charged bodies. Immersed in a conductive medium, they interact continuously—and sometimes explosively—with their celestial environment.

Today, nothing is more important to the future and credibility of science than liberation from the gravity-driven universe of prior theory. A mistaken supposition has not only prevented intelligent and sincere investigators from seeing what would otherwise be

A logarithmic chart of the electro- magnetic spectrum reveals how narrow is the range of visible light. The shorter wavelengths emitted by celestial bodies (most ultraviolet light, X-rays and Gamma Rays) do not reach the surface of the Earth and can only be measured by instruments placed in space. On the other hand, radio waves between about a centimeter to 10 meters in wavelength find the atmosphere transparent. As a result, earth-based radio tele- scopes have become an important adjunct to traditional astronomy.

Celestial Objects Seen Up Close

Crab Nebula as viewed in the mid-20th century.

On July 4, 1054 AD, Chinese chroniclers recorded an apparent supernova they called a "guest star" in the constellation Taurus, near the star Zeta Tauri. It was bright enough to be visible in daylight, but faded and disappeared again about a year later. In 1731 astronomer John Bevis discovered a bright neb- ula in the same location. When Charles Messier saw it in 1758, he first thought this "fuzzy object" might be a comet, but he found that it never moved.

Using a larger telescope in 1844, Lord Ross thought the nebula resembled a crab's claw, and the description stuck. More than ten light years across, the Crab Nebula is thought to be the remains of a star that exploded in 1054.

Today's astronomical instruments see much more than Messier's fuzzy patch. They see filaments and complex structures, in colors and wavelengths that highlight newly discovered phenomena.For example, the star at the center of the nebula blinks 30 times a second. We now call such stars "pulsars."

This high-resolution picture of the Crab Nebula, taken by the Very Large Telescope (VLT), shows the filamen- tation produced by magnetic fields and electric currents, with material racing outward at "higher speed than expected from a free explosion," according to NASA reports. Acceleration of particles is a trademark of elec- trical activity.

In this photograph taken by the Chandra X-Ray Tele- scope, we see the internal structure and dynamics of the Crab Nebula—a torus around a polar column, or a "doughnut on a stick." Plasma physicists find this of par- ticular interest because x-ray activity always accompa- nies high-energy electrical interactions.

One of a series of Hubble Space Telescope images showing filamentary material racing away from the core of the Crab Nebula at half the speed of light, giving rise to what NASA spokesmen call "a scintillating halo, and an intense knot of emission dancing, sprite-like, above the pulsar's pole." Though gravitational theories never envisioned the polar "jets," "haloes," and "knots" depicted in the accompanying images we can now rec- ognize these configurations as prime examples of elec- trical forces in the universe.

obvious, it has bred an indifference to possibilities that could have inspired the sciences for decades. It has also obscured the link between new findings in space and the human past, a link with implications far beyond the physical sciences.

Plasma Phenomena in Ancient Times

The discovery of the “electric universe” does not just change the picture of the heavens. It also changes what we see and hear in messages from the ancient world. Over the past century and a half, archaeologists have unearthed huge libraries of archaic texts, many of them describing great spectacles in the heavens. But the special- ists set aside these descriptions as "untrustworthy" because they accepted a priori the uneventful solar system assumed by astrono- mers. Most historians do not doubt that the ancient sky looked almost exactly like our sky today. Consequently, they give little or no attention to the "extravagant" or "nonsensical" claims of early sky worshippers.

But were it possible for us to stand alongside our early ances- tors, to witness the events that provoked the age of myth-making and the birth of the archaic religions, the celestial dramas would exceed anything conceivable in our own time. The sky was electric, filled with luminous clouds, threads of light, and undulating rivers of fire. To today’s observer the events could only appear too vast, too improbable for anything but a dream.

A portrait of the center of our Milky Way galaxy constructed from radio data. NASA spokesmen note "the arcs, threads, and filaments which abound in the scene. Their uncer- tain origins challenge present the- ories of the dynamics of the galactic center." Arcs, threads and filaments are typical forms of elec- trical discharge in plasma.

Yet to a modern-day witness the formations in the sky would also seem eerily familiar, as if remembered.

In these pages we contend that humans living today have seen the events before, through their universal reflection in art and story- telling. Formations now known to be characteristic of electric dis- charge in plasma are the core images of the antique world, recorded on papyrus and stone, mirrored in the sacred symbols of the great religions, reenacted in mystery plays, and embodied in monumental construction on every habitable continent. Once recognized, the images leap from every ancient culture. The sky was once a theater of awe and terror: on this the ancient witnesses speak with one accord.

Solar prominences reveal the powerful influence of magnetic fields. However, magnetic fields require electric currents, and the fields alone do not cause the prominences. The picture on the right is direct evidence of electrical discharge on the Sun.

Unique Behavior of Plasma

Although plasma behavior follows simple electromagnetic laws, the resulting complexity continues to astonish the specialists who study it. Because plasma exhibits characteristics not found in solids, liquids, or gases, it has been called "the fundamental state of matter." It can self-organize into cells of differing electrical charac- teristics. Electric currents in plasma form filaments that attract each other at long distances and repel each other at short distances. These filaments tend to braid themselves into "ropes" that act as power transmission lines, with virtually no limit to the distances over which they can operate.

In the rarefied plasma of space, the subtle flow of electricity is not easily measured, but these currents leave a definitive signa-

ture—a network of magnetic fields throughout the observed uni- verse. Astronomers detect these fields but give no attention to the electric cause: magnetic fields are produced only by electricity. The complex magnetic fields we observe are evidence that plasma is carrying electrical energy across galactic and intergalactic space, powering secondary systems, including galaxies, stars, and planets. Exceedingly subtle charge imbalances, across the immense volume of space, are quite sufficient to configure and animate cosmic struc- tures at all scales of observation. The reason for this power of elec- tricity is very simple: the electric force is 1039 times (a thousand billion, billion, billion, billion times) more powerful than gravity. Contrary to popular belief nature does not rely on the trivially weak force of gravity to do the “really big jobs” in the cosmos.

To see the connection between plasma experiments and plasma formations in space, it is essential to understand the scalability of plasma phenomena. Under similar conditions, plasma discharge will produce the same formations irrespective of the size of the event. The same basic patterns will be seen at laboratory, planetary, stellar, and galactic levels. Duration is proportional to size as well. A spark that lasts for microseconds in the laboratory may continue for years at planetary or stellar scales, or for millions of years at galactic or intergalactic scales.

The scalability of plasma events enables researchers, utilizing laboratory experiments and supercomputer simulation, to replicate stellar and galactic evolution, including many enigmatic formations only recently discovered in deep space. Gravitational models do not achieve comparable success, and often fail completely.

Many of astronomy’s most fundamental mysteries now find their resolution in plasma behavior. Why do cosmic bodies spin,

Spiral galaxy M81, in one of the first images returned by NASA’s new Spitzer space telescope. The tele- scope can detect extremely faint waves of infrared radiation, or heat, through clouds of dust and plasma that have blocked the view of con- ventional telescopes.

Photograph of the comet Hale Bopp, taken April 7, 1997 as it receded from the Sun, passing in front of a star cluster in the con- stellation Perseus. In addition to the dust tail of the comet, the fila- mentary bluish ion tail (positively charged particles) testifies to elec- trical behavior of comets only recently recognized.

asked the distinguished astronomer Fred Hoyle, in summarizing the unanswered questions. Plasma experiments show that rotation is a natural function of interacting currents in plasma. Currents can pinch matter together to form rotating stars and galaxies. A good example is the ubiquitous spiral galaxy, a predictable configuration of a cosmic-scale discharge. Computer models of two current fila- ments interacting in a plasma have, in fact, reproduced fine details of spiral galaxies, where the gravitational schools must rely on invisible matter arbitrarily placed wherever it is needed to make their models "work."

It is worth noting also that plasma experiments, backed by com- puter simulations of plasma discharge, can produce galactic struc- tures without recourse to a popular fiction of modern astrophysics—the Black Hole. Astronomers require invisible, super-compressed matter as the center of galaxies because without Black Holes gravitational equations cannot account for observed movement and compact energetic activity. But charged plasma achieves such effects routinely.

Planets, Comets, and Plasma Discharge

The new revelations of plasma science enable us to see that planets are charged bodies moving through a weak electric field of the Sun. Astronomers do not recognize planetary charge because the planets now move on nearly circular orbits. The change in elec- tric potential during a revolution is so minimal as to pro-

duce no obvious effects. (We take up the subtle indicators of planetary circuits in our second mono- graph; these indicators include auroras, weather patterns, lightning, dust devils, water spouts, and tornadoes.)

It is easier to see the electric force in action when a comet approaches the Sun on an elongated orbit that car- ries it quickly into regions of greater electrical stress. Plasma will form a cell, or “sheath,” around any object within it that has a different electric potential. If the potential difference is low, the plasma sheath will be

invisible. This is the case with the planets, whose plasma sheaths are called “magnetospheres” because the planetary magnetic field is trapped inside. Unlike a planet, however, a comet spends most of its time far from the Sun and takes on a charge in balance with that region of the Sun’s electric field. As it speeds toward the Sun, its charge is increasingly out of balance with its surroundings. Eventu- ally, the plasma sheath glows in response to the electric stresses. This is what we see as the coma and ion tail of a comet. The dust tail is formed when more intense discharge—in the form of an elec- tric arc to the comet nucleus—removes surface material and

launches it into space. The internal electric stress may even blow the comet apart—as often and "inexplicably" occurs!

Our claim that comets are electrical in nature can be easily tested. Are comet nuclei "wet" or "dry"? The standard model of comets explains them as "dirty snowballs" sublimating under the heat of the Sun. Escaping water vapor generates the coma and is "blown" away by the solar wind to produce the diffuse tail spanning up to millions of miles. In the electrical model a large rock containing no volatiles (ices) but on an elliptical orbit will still generate a coma and tail as electric discharge excavates material from the surface. The standard comet model, however, will not survive the discovery of a comet nucleus free of vola- tiles.

Already, the comet question is being answered. As the spacecraft Deep Space 1 flew by the nucleus of Comet Borrelly, it found that the surface was "hot and dry." Instruments detected not a trace of water on the surface. The only water dis- covered was in the coma and tail, where it could easily be explained by reactions of negatively charged oxygen from the nucleus with positively charged hydrogen ions from the Sun.

These reactions are, in fact, observed. But with no other model than that of the dirty snowball, astronomers could only assume that water must be present on the nucleus but hidden beneath the sur- face.

Then, NASA's Stardust probe to comet Wild-2 (pronounced vilt

2) startled investigators with the best pictures ever of a comet. In its approach to the comet, short but intense bursts of microscopic dust from the comet blasted the spacecraft as it crossed two jets. "These things were like a thunderbolt," said Anthony Truzollino, a Senior Scientist at the University of Chicago's Enrico Fermi Institute. To the bafflement of project scientists, the pictures showed sharply defined “spires, pits and craters”—just the opposite of the attenu- ated relief expected of an evaporating snowball. The discovery was more than surprising, "it was mind-boggling," the scientists said. But a ruggedly etched landscape is predicted by the electric model.

Plasma Cosmology—The Leading Edge of Science

Two early twentieth century pioneers whose work leads to a deeper understanding of plasma and electricity are Sweden’s Kris- tian Birkeland and America’s Irving Langmuir. Experiments inspired by Birkeland’s work showed how current filaments in plasma join in entwined pairs, now called “Birkeland currents.” (See illustration and discussion, page 24.) Langmuir’s experimental work gave rise to the word "plasma," due to the life-like behavior of

Comet Wild 2, in a composite of the nucleus and a longer exposure high- lighting the comet's jets. Stardust mission scientists expected "a dirty, black, fluffy snowball" with a couple of jets that would be dispersed into a halo. Instead they found more than two dozen jets that "remained intact"—they did not disperse in the fashion of a gas in a vacuum. Some of the jets emanated from the dark unheated side of the comet—an anomaly no one had expected.

Plasma scientist Anthony Peratt.

RIGHT: Snapshots from a computer simulation by Peratt, illustrate the evolution of galactic structures.

Through the “pinch effect,” parallel currents converge to produce spi- raling structures.

this conductive medium, and he demonstrated how the plasma “sheath” insulates a charged sphere from its plasma environment. This sheath is now crucial to the understanding of the so-called "magnetospheres" of planets, though few astronomers take into account the electrical implications.

One of the most respected innovators was Nobel Laureate Hannes Alfvén, honored as the father of “plasma cosmology,” an approach to cosmic evolution based on electric forces. It was Alfvén who developed the first models of galactic structure and star formation rooted in the dynamics of electrified plasma, and his challenges to the “pure mathematics” of modern cosmology arose from experimental evidence that has grown increasingly persuasive in recent years.

Alfven’s close colleague, Anthony Peratt, later extended his investigation, conducting experiments with far-reaching implica- tions for the understanding of galaxies, stars, and the evolution of planetary systems. From graduate school until Alfvén's death in 1995, Peratt worked with the pioneer to define the frontiers of plasma cosmology, a subject highlighted in the physicist Eric Lerner’s popular book, The Big Bang Never Happened. Peratt’s

work included unprecedented three-dimensional simulations of gal- axy evolution and of other plasma structures in space. Today he is internationally recognized as an authority on plasma discharge instabilities and their three-dimensional simulation

Using equations that describe the interactions of electric and magnetic fields (Maxwell-Lorentz equations), Peratt developed a super computer program to mimic the effects of electric discharge within a large volume of charged particles. His "Particle in Cell" (PIC) simulations have produced formations that are virtually indis- tinguishable from the energetic patterns of actual galaxies, as can be seen in the graphic below.

Peratt’s book The Physics of the Plasma Universe has led the way to a new understanding of high-energy plasma behavior and the role of electricity in the cosmos. Due in large part to the Coali- tion of Plasma Science, of which Peratt is a member, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the world's largest scientific and technical society, announced that it would recognize “Plasma Cosmology” as an official discipline in science.

Plasma Discharge Inscribed on Stone

For over three decades Peratt’s laboratory research concentrated on the unstable formations that develop in high-energy plasma dis- charge, and he recorded the evolution of these configurations through dozens of phases. Some of the most elaborate discharge forms are now called “Peratt Instabilities” because he was the first to document them.

His most recent work has taken him in a new direction, and the results offer the strongest link between plasma science and things once seen in the sky. In September, 2000, in response to communi- cations with the authors of this monograph, Peratt became intrigued by the striking similarity of ancient rock art to plasma discharge

Anthony Peratt’s “Particle in Cell” (PIC) simulations have demon- strated the way electric forces gen- erate galactic structure. In the examples of three galaxies shown here, the simulated energy pat- terns match observed patterns with surprising accuracy.

These rock art examples of the “squatter man” from around the world illustrate one of the many global patterns. Samples gathered by Anthony Peratt.

Peratt’s graphic representation of a plasma configuration produced in laboratory experiments. The geom- etry relates directly to the rock art “squatter man” discussed on these pages.

A three-dimensional idealized repre- sentation of the transparent “hour- glass” discharge pattern, together with a white-on-black image of the same configuration. Were such a formation to have appeared in the ancient sky, a rock drawing of it would probably look like the image on the right, similar to the “squatter man of worldwide rock art.

formations. Suddenly he was seeing, carved on stone by the tens of thousands, the very forms he had documented in the laboratory. The correlations were so precise—down to the finest details—that they could not be accidental. The artists were recording heaven-span- ning discharge formations above them.

In his investigation of rock art themes, Peratt concentrated his field work in the American Southwest and Northwest, but he also gathered data internationally. For his on-site study he used GPS longitude and latitude positions, always noting the probable orien- tation or field of view. A team of about 30 volunteers, including specialists from several fields, assisted Peratt in the investigation, and he has since gathered more than 25,000 rock art images. While the recorded formations correspond to nothing visible in the heav- ens today, they accurately depict the evolution of plasma instabili- ties. Peratt reports that "some 87 different categories of plasma instabilities have been identified among the archaic petroglyphs and there exists nearly none whose whole or parts do not fit this delin- eation."

A plasma instability found globally in rock art is a stick figure with a circle or dot on each side of its torso. In plasma experiments, this “squatter man” configuration appears when a disk or donut-like torus is bent by magnetic fields induced by the current flow. From the viewpoint of the observer, the edges of the upper disk may appear to point up (forming "arms") and those of the lower torus may appear to point down (forming "legs"). The underlying “hour- glass” pattern, with many subtle variations, occurs around the world.

Virtually all of the variations in the ancient drawings corre- spond to known evolutionary aspects of the basic plasma form. To appreciate the potential evolution, it is essential that one visualize the configuration three dimensionally, as illustrated by the idealiza- tion of the form below—

The graphic image of the discharge configuration above utilizes a tonal gradient to indicate the structure of a transparent plasma discharge, where this structure would not be self evident in a rendi- tion carved on rock.

Our idealized formation shows slight variations between the upward-pointing and downward-pointing components, consistent with common variations in the laboratory and in rock art. The upper “champaign glass” form results from a distortion of a flattened tor- oidal disk as the edges curve upward. In the warping of the disk below, the downward curvature is interrupted at the extremity, which bends outward to create a “squashed bell” appearance. The rock art images given on page 21 include other variations as well.

Often, the “arms” and “legs” of the “squatter man” are more squared than in our graphic representation here (examples on right), but this variation too is characteristic of laboratory discharge.

Our illustration of the hourglass discharge form accents the cen- tral torus and its visual relationship to the two symmetrical dots or circles seen in the corresponding rock art images. But many other nuances of such discharge configurations must be taken into account. It is unlikely that this torus would have always been visi- ble, for example, and a great number of “squatter man” rock art images do not display the two dots or spheres. Also, the warping of the upward and downward extremities of the hourglass form can occur in almost limitless variations. A more comprehensive treat- ment of this subject would require systematic analysis of the global variations in the rock art forms, comparing the wide-ranging pat- terns to the implied discharge evolution.

A New Approach to Rock Art

Peratt’s findings are particularly significant in their contrast to traditional explanations of rock art. The majority of rock art author- ities, particularly those with primary interest in Native American sources, argue that only images of the sun, moon, and stars reflect actual celestial phenomena. Apart from such associations, most authorities claim that global patterns do not exist. Peratt’s investi- gations say the opposite, confirming numerous universal patterns of rock art. Through massive labors, some apparently taking whole lifetimes according to Peratt, the ancient artists recorded immense discharge phenomena in the heavens.

Following an intensive investigation, Peratt began summarizing his findings. He wondered if the ancient artists might have wit- nessed an episode of high-energy plasma incursion into Earth’s atmosphere, what he called an "enhanced aurora." His first article, “Characteristics for the Occurrence of a High-Current, Z-Pinch

Examples of the “Squatter man” figures, with twin dots or circles of the left and right, from the Ameri- can southwest.

Electric currents in plasma naturally form filaments due to the squeezing or "pinch effect" of the surrounding self-generated toroidal magnetic field. Complex electromagnetic interactions cause the filaments to rotate about each other to form a “Birkeland Current” pair. In high energy discharge sequences these rotating currents can evolve vio- lently into a stack of disks or toruses around the discharge axis.

ABOVE: Graphic illustration of the stacked toruses in the Peratt Insta- bility on the left. Computer simula- tion of the experimental results on the right.

Aurora as recorded in Antiquity,” was published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, in its Transactions on Plasma Science for December 2003. Here he states his conclusion forth- rightly: the recurring petroglyph patterns “are reproductions of plasma phenomena in space.”

Stacked Toruses

In laboratory experiments and in computer simulations, Peratt demonstrated how electric forces in a plasma discharge generate rapidly changing configurations. One of the most common and fas- cinating patterns is a stack of disks or toruses (donut-like rings) around a central axis, a configuration that evolves through many variations. This dynamic sequence culminates in a highly energetic collapse. But according to Peratt, the prior phases of the stacked toruses are relatively stable and numerous variations were inscribed on stone everywhere in the world.

The discharge sequence leading to the stacked toruses begins with two braided current filaments ("Birkeland currents," named after Kristian Birkeland), as illustrated on the left. Under the mag- netic forces generated by the currents, the two filaments tend to draw closer. As they do so, they rotate about each other faster and faster. If the current is strong enough, it may "pinch off" in what is known as a "sausage" instability, forming a series of cells that look like a string of sausages or a string of pearls.

The sausage “links” then form spheroids that evolve into disks or toruses (thick rings or “donuts”) of electrical current circling the initial line current (two images on the right). This formation remains stable for a relatively long period, accreting matter at the center of each torus.

As the sequence progresses, the disks or toruses will flatten and the outer edges will begin to curve upward or downward like the rims of a saucepan. To an observer looking through the transparent toruses they will have the appearance of stacked “arms” or “legs” strung along the axis of the discharge. Of such a configuration, thousands of examples exist around the world.

Eventually the formation reaches a threshold point and explo- sively breaks apart. This culminating phase of the discharge sequence is so energetic that direct human observation of such a configuration close to Earth would likely be deadly.

Nevertheless, an exceedingly rare but precise replication of this phase is given in a petroglyph from Kayenta, Arizona (above). When Peratt received this image from one of the authors (Talbott),

he had no doubt of its significance. The configuration’s unique fea- tures make the plasma explanation definitive, Peratt reported.

Terminus Plasma Column

(Birkeland Currents) Diocotron Instability

torus (plasmoid)

Pictograph from Kayenta, Arizona.

The upper terminus shows the twin filaments of tightly bound Birkeland currents of the plasma column below. In high energy dis- charge, the terminal filaments typically flare out as the discharge column evolves. The flat disks or toruses with upturned edges (“saucepan” formations) are typical of diocotron instabilities, rap- idly revolving plasma contained and configured by magnetic fields. At the “base” of the formation is a larger, thicker and transparent torus, permitting the observer to see through the inner shells, pre- senting a view that might be compared to an automobile tire cut in half and viewed edge on.

Peratt writes—

Six flattened tori [toruses] are depicted … whose features can be shown to be exact in detail. The spacing and the shape of the ‘bars’ as well as the fine structure at the tips of the disks are precise. Slight cur- vature in the ‘bars’ indicates that state transition is imminent. It should also be noted that the lowest disk is about one-half the size of the stack above. The stack also opens out slightly in the direction of

ABOVE: illustration of the suggested three-dimensional appearance of the plasma form that inspired the Kayenta petroglyph on the left.

ABOVE: In this Australian rock art image, the upper twin filaments have spawned secondary radial fil- aments, a characteristic feature of intense plasma discharge.

LEFT: These enigmatic rock art images from the American south- west represent a few of the thou- sands of examples capturing the complex evolution of toroidal for- mations, or “Peratt Instabilities.”

Peratt’s computer simulations of the plasma torus reveal the dynam- ics of the ancient “eye mask” form, while also giving a new perspective on the “owl” in cross-cultural sym- bolism (below).

ABOVE: “eye mask” formation stands in intimate connection to the arche- type of the mother goddess, often called the “eye goddess” and some- times taking the form of an “owl.” Here we see the owl form of the Greek goddess Athene.

RIGHT: drawings of the “eye mask” from Easter Island.

the terminus. The geometrical shape of the terminus … is an exact representation of experimental data.

Peratt reports that this pictograph represents "the onset of a cha- otic change of state." This is the most energetic phase, meaning that humans would have needed to shield themselves from the intense radiation at all cost. It is not surprising that direct pictorial repre- sentations of this phase are almost non-existent, in contrast to ear- lier phases recorded by the tens of thousands.

Eye Mask

A key component in the Kayenta pictograph above is the "eye mask" seen at the base of the image. For decades this elementary form has intrigued symbolists and rock art specialists, but no con- sensus was ever reached as to its meaning.

Occurrences of the "eye mask" on stone and in ancient art range from Easter Island in the southern hemisphere to North America, Europe, ancient Mesopotamia, and elsewhere. If primitive artists were recording something they saw in the sky, then there can be no doubt that it was seen from both hemispheres.

Peratt immediately identified the eye mask as a "low opacity torus,” or thick ring, seen from a vantage-point not too far from the plane of the torus. The most intense currents in a plasma torus are concentrated at the center and surrounded by a number of concen- tric "shells." Because the outer shells have a low opacity, an observer can see deeply inside the torus. The center of the torus cross-section becomes more visible at optical wavelengths as the outer plasma shells become less opaque. In addition, the torus tends to flatten with increasing current, a characteristic revealed by innu- merable instances of the eye mask globally and as seen in the ancient Sumerian symbols of the goddess Inanna (right) and the Native American “She Who Watches” below—

A “Complete Match”

Peratt was impressed not only by the precise accord of rock art images to experimental and simulated forms, but also by the detailed correspondences between images in different parts of the world. He only needed to adjust for the different lines of sight to obtain remarkably accurate overlays. An example of this is seen below, in a category of images Peratt calls the "Stonehenge" type. Here, Peratt overlays a "Wandjina" pictograph in Northeastern Aus- tralia (1) with a carved granite petroglyph in northeastern Arizona (2). To adjust for divergent lines of sight, he digitally tilted the latter

45.3 degrees. Then the fit was perfect (3), despite the fact that the radiating streamers in the two images were not symmetrical.

The overlay is so exact that the only way I could illustrate this was to extrude the Arizona petroglyph (in white) and lay a flat black Wand-

“Eye-idols” of the Sumerian god- dess Inanna.

“She Who Watches,” a popular eye goddess of the Columbia River region in the northwestern U.S.

jina on top. That is, everywhere you see black on white, even the edges, is the overlay. This technique still does not do the overlay jus- tice …. My claim that at least a lifetime was spent carving some of these petroglyphs in granite with stone instruments is based on both the overlay factor and comparison to experimental data.

The presence of identical images around the world is a common theme in Peratt’s cataloging of ancient art. "An appreciable number of the categories contain petroglyphs that overlay to the degree that they are ‘cookie cutter’ templates of each other," he states. Through computer processing his data enable him to project what was seen in the sky in three dimensions. The pictographs themselves can be arranged to form animation cells, enabling him to produce an ani- mation of the laboratory sequences using only the pictographs—a complete match between the images on stone and the complex evo- lution of the plasma instabilities.

It now appears that dating of the events is also possible. Where various figures have been painted on stone and the pigments have leached into the rock, leaving a residue that is still present, a tech- nique called “plasma extraction” may yield valuable estimates as to when the events occurred. Indeed, Peratt exudes confidence on the matter, saying that if plasma scientists can cross reference the dates from plasma extraction with laboratory data on the discharge sequence, "extracting dates seems certain." He presently estimates that the 87 categories generally fall in a range from 7,000 BC to 3,000 BC. This brings the rock art expressions directly in line with the formative phase of the first civilizations, raising profound ques- tions about the antique cultures. What were the cosmic influences shaping human imagination in this enigmatic period of human his- tory?

Today, more than a dozen qualified individuals, constituting an interdisciplinary nucleus, are working to reconstruct details of the ancient celestial dramas. Though the individuals come from diverse fields of inquiry, all agree that the accord between ancient images and plasma configurations is too detailed and too specific to be explained as accidental convergence. All have concluded that

immense discharge formations appeared in the sky of ancient wit- nesses and that the violent evolution of these formations must have instilled overwhelming terror.

A New Approach

In the present inquiry science and historical testimony con- verge, requiring a radical reassessment of each in the light of the other. Laboratory experiments not only offer a new perspective on the physical universe, they connect the leading edge of science to a critical phase of human history. Disciplines that previously devel- oped in isolation now require interdisciplinary communication. The physical sciences on the one hand, and the study of archaic human memories on the other, are brought into alignment by questioning the assumptions that have affected both. What, for example, can the reconstructed plasma formations tell us about the origins of ancient religions, mythology, and symbolism? How might they explain the mystery to which we alluded in the first pages of this monograph-- the recurring themes of the mother goddess, the hero, and the chaos dragon?

Our hope is that doors will open to more holistic approaches within the sciences, encouraging even specialists, confident in their long-held assumptions, to wonder again about our universe, the evolution of Earth, and the influence of cosmic events on human history.