Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime

Reality is a Dream

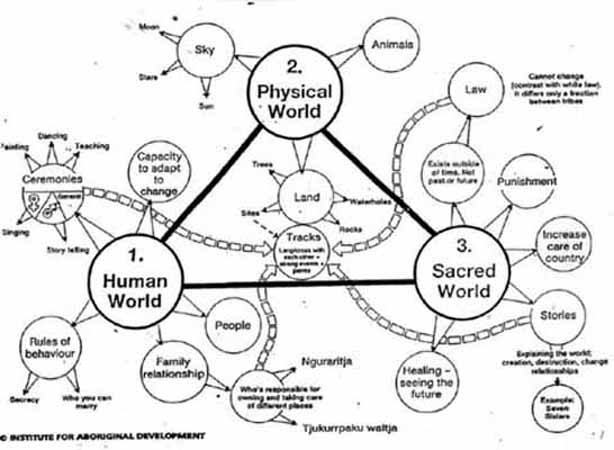

In the animist framework of Australian Aboriginal mythology, The Dreaming is a sacred era in which ancestral Totemic Spirit Beings formed The Creation.

"Dreaming" is also often used to refer to an individual's or group's set of beliefs or spirituality. For instance, an indigenous Australian might say that he or she has Kangaroo Dreaming, or Shark Dreaming, or Honey Ant Dreaming, or any combination of Dreamings pertinent to their "country". Many Indigenous Australians also refer to the Creation time as "The Dreaming". The Dreamtime laid down the patterns of life for the Aboriginal people.

Dreaming stories vary throughout Australia, with variations on the same theme. For example, the story of how the birds got their colors is different in New South Wales and in Western Australia. Stories cover many themes and topics, as there are stories about creation of sacred places, land, people, animals and plants, law and custom. It is a complex network of knowledge, faith, and practices that derive from stories of creation. It pervades and informs all spiritual and physical aspects of an indigenous Australian's life.

They believe that every person essentially exists eternally in the Dreaming. This eternal part existed before the life of the individual begins, and continues to exist when the life of the individual ends. Both before and after life, it is believed that this spirit-child exists in the Dreaming and is only initiated into life by being born through a mother. The spirit of the child is culturally understood to enter the developing fetus during the fifth month of pregnancy.

When the mother felt the child move in the womb for the first time, it was thought that this was the work of the spirit of the land in which the mother then stood. Upon birth, the child is considered to be a special custodian of that part of his country and is taught the stories and song lines of that place. As Wolf (1994: p. 14) states: "A black 'fella' may regard his totem or the place from which his spirit came as his Dreaming. He may also regard tribal law as his Dreaming."

It was believed that, before humans, animals, and plants came into being, their 'souls' existed; they knew they would become physical, but not when. And when that time came, all but one of the 'souls' became plants or animals, with the last one becoming human and acting as a custodian or guardian to the natural world around them.

Traditional Australian indigenous peoples embrace all phenomena and life as part of a vast and complex system-reticulum of relationships which can be traced directly back to the ancestral Totemic Spirit Beings of The Dreaming. This structure of relations, including food taboos, had the result of maintaining the biological diversity of the indigenous environment. It may have helped prevent overhunting of particular species.

The Dreaming establishes the structures of society, rules for social behavior, and the ceremonies performed to ensure continuity of life and land. The Dreaming governs the laws of community, cultural lore and how people are required to behave in their communities. The condition that is The Dreaming is met when people live according to law, and live the lore: perpetuating initiations and Dreaming transmissions or lineages, singing the songs, dancing the dances, telling the stories, painting the songlines and Dreamings.

The Creation was believed to be the work of culture heroes who travelled across a formless land, creating sacred sites and significant places of interest in their travels. In this way songlines were established, some of which could travel right across Australia, through as many as six to ten different language groupings. The songs and dances of a particular songline were kept alive and frequently performed at large gatherings, organised in good seasons.

In the Aboriginal world view, every event leaves a record in the land. Everything in the natural world is a result of the actions of the archetypal beings, whose actions created the world. Whilst Europeans consider these cultural ancestors to be mythical, many Aboriginal people believe in their literal existence. The meaning and significance of particular places and creatures is wedded to their origin in the Dreaming, and certain places have a particular potency, which the Aborigines call its dreaming.

In this dreaming resides the sacredness of the earth. For example, in Perth, the Noongar believe that the Darling Scarp is said to represent the body of a Wagyl - a serpent being that meandered over the land creating rivers, waterways and lakes. It is taught that the Wagyl created the Swan River. In another example, the Gagudju people of Arnhemland, for which Kakadu National Park is named, believe that the sandstone escarpment that dominates the park's landscape was created in the Dreamtime when Ginga (the crocodile-man) was badly burned during a ceremony and jumped into the water to save himself. He turned to stone and became the escarpment. The common theme in these examples and similar ones is that topographical features are either the physical embodiments of creator beings or are the results of their activity.

In one version (there are many Aboriginal cultures), Altjira was the god of the Dreamtime; he created the Earth and then retired as the Dreamtime vanished. Alternative names for Altjira in other Australian languages include Alchera (Arrernte), Alcheringa, Mura-mura (Dieri), and Tjukurpa (Pitjantjatjara).

The dreaming and travelling trails of the Spirit Beings are the songlines (or "Yiri" in the Warlpiri language). The signs of the Spirit Beings may be of spiritual essence, physical remains such as petrosomatoglyphs of body impressions or footprints, amongst natural and elemental simulacrae. To cite an example, people from a remote outstation called Yarralin, which is part of the Victoria River region, venerate the spirit Walujapi as the Dreaming Spirit of the black-headed python. Walujapi carved a snakelike track along a cliff-face and left an impression of her buttocks when she sat establishing camp. Both these dreaming signs are still discernible. In the Wangga genre, the songs and dances express themes related to death and regeneration. They are performed publicly with the singer composing from their daily lives or while Dreaming of a nyuidj (dead spirit).

Many non-native writers and artists have been inspired by Dreamtime concepts for film literature and other media projects.

Australian Aboriginal Mythology

Australian Aboriginal myths (also known as Dreamtime stories, Songlines or Aboriginal oral literature) are the stories traditionally performed by Aboriginal peoples within each of the language groups across Australia.

All such myths variously tell significant truths within each Aboriginal group's local landscape. They effectively layer the whole of the Australian continent's topography with cultural nuance and deeper meaning, and empower selected audiences with the accumulated wisdom and knowledge of Australian Aboriginal ancestors back to time immemorial.

Australian Aboriginal mythologies have been characterised as "at one and the same time fragments of a catechism, a liturgical manual, a history of civilization, a geography textbook, and to a much smaller extent a manual of cosmography."

There are 400 distinct Aboriginal groups across Australia, each distinguished by unique names usually identifying particular languages, dialects, or distinctive speech mannerisms. Each language was used for original myths, from which the distinctive words and names of individual myths derive.

With so many distinct Aboriginal groups, languages, beliefs and practices, scholars cannot attempt to characterise, under a single heading, the full range and diversity of all myths being variously and continuously told, developed, elaborated, performed, and experienced by group members across the entire continent. The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia nevertheless observes: "One intriguing feature of Aboriginal Australian mythology is the mixture of diversity and similarity in myths across the entire continent."

Australian anthropologists willing to generalize suggest Aboriginal myths still being performed across Australia by Aboriginal peoples serve an important social function amongst their intended audiences: justifying the received ordering of their daily lives; helping shape peoples' ideas; and assisting to influence others' behavior. In addition, such performance often continuously incorporates and "mythologies" historical events in the service of these social purposes in an otherwise rapidly changing modern world.

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, The Dreaming or Altjeringa (also called the Dreamtime) is a sacred 'once upon a time' time out of time in which ancestral Totemic Spirit Beings formed The Creation.

The Dreamtime contains many parts: It is the story of things that have happened, how the universe came to be, how human beings were created and how the Creator intended for humans to function within the cosmos.

The expression 'Dreamtime' is most often used to refer to the 'time before time', or 'the time of the creation of all things', while 'Dreaming' is often used to refer to an individual's or group's set of beliefs or spirituality.

For instance, an Indigenous Australian might say that they have Kangaroo Dreaming, or Shark Dreaming, or Honey Ant Dreaming, or any combination of Dreamings pertinent to their 'country'. However, many Indigenous Australians also refer to the creation time as 'The Dreaming'.

What is certain is that 'Ancestor Spirits' came to Earth in human and other forms and the land, the plants and animals were given their form as we know them today.

These Spirits also established relationships between groups and individuals, (whether people or animals) and where they traveled across the land, or came to a halt, they created rivers, hills, etc., and there are often stories attached to these places.

Once their work was done, the Ancestor Spirits changed again; into animals or stars or hills or other objects. For Indigenous Australians, the past is still alive and vital today and will remain so into the future. The Ancestor Spirits and their powers have not gone, they are present in the forms into which they changed at the end of the 'Dreamtime' or 'Dreaming', as the stories tell.

The stories have been handed down through the ages and are an integral part of an Indigenous person's 'Dreaming'.

Each tribe has its individual dreamtime although some of the legends overlap. Most 'Dreamtime' originates with the Giant Dog or the Giant Snake, and each is unique and colorful in its explanation.

Legends of the 'Dreamtime' are handed down by word of mouth and by totem from generation to generation. It involves secret rituals and rites, and some classified as 'Men's Business' and some as 'Women's Business'. Colorful, symbolic and enthusiastic dancing and corroborees are used to pass on the stories of the creation.

The Australian Aborigines speak of jiva or guruwari, a seed power deposited in the earth. In the Aboriginal world view, every meaningful activity, event, or life process that occurs at a particular place leaves behind a vibrational residue in the earth, as plants leave an image of themselves as seeds. The shape of the land - its mountains, rocks, riverbeds, and water holes - and its unseen vibrations echo the events that brought that place into creation. Everything in the natural world is a symbolic footprint of the metaphysical beings whose actions created our world. As with a seed, the potency of an earthly location is wedded to the memory of its origin.

The Aborigines called this potency the "Dreaming" of a place, and this Dreaming constitutes the sacredness of the earth. Only in extraordinary states of consciousness can one be aware of, or attuned to, the inner dreaming of the Earth.

"Dreaming" is also often used to refer to an individual's or group's set of beliefs or spirituality. For instance, an Indigenous Australian might say that they have Kangaroo Dreaming, or Shark Dreaming, or Honey Ant Dreaming, or any combination of Dreamings pertinent to their "country". However, many Indigenous Australians also refer to the creation time as "The Dreaming". The Dreamtime laid down the patterns of life for the Aboriginal people.

Dreaming stories vary throughout Australia, and there are different versions on the same theme. For example, the story of how the birds got their colors is different in New South Wales and in Western Australia. Stories cover many themes and topics, as there are stories about creation of sacred places, land, people, animals and plants, law and custom. It is a complex network of knowledge, faith, and practices that derive from stories of creation, and which pervades and informs all spiritual and physical aspects of an indigenous Australian's life.

They believe that every person in an essential way exists eternally in the Dreaming. This eternal part existed before the life of the individual begins, and continues to exist when the life of the individual ends. Both before and after life, it is believed that this spirit-child exists in the Dreaming and is only initiated into life by being born through a mother. The spirit of the child is culturally understood to enter the developing fetus during the 5th month of pregnancy.

When the mother felt the child move in the womb for the first time, it was thought that this was the work of the spirit of the land in which the mother then stood. Upon birth, the child is considered to be a special custodian of that part of their country and taught of the stories and songlines of that place. As Wolf (1994: p.14) states: "A black 'fella' may regard his totem or the place from which his spirit came as his Dreaming. He may also regard tribal law as his Dreaming."

It was believed that, before humans, animals, and plants came into being, their 'souls' existed by themselves; they knew they would become physical, but not when. When that time came, all but one of the 'souls' became plants or animals, with the last one becoming human and acting as a custodian or guardian to the natural world around them. Traditional Australian indigenous peoples embrace all phenomena and life as part of a vast and complex system-reticulum of relationships which can be traced directly back to the ancestral Totemic Spirit Beings of The Dreaming. This structure of relations, including food taboos, was important to the maintenance of the biological diversity of the indigenous environment and may have contributed to the prevention of overhunting of particular species.

The Dreaming establishes the structures of society rules for social behaviour and the ceremonies performed in order to ensure continuity of life and land. The Dreaming governs the laws of community, cultural lore and how peoples are required to behave in their communities. The condition that is The Dreaming is met when peoples live according to law, and live the lore: perpetuating initiations and Dreaming transmissions or lineages, singing the songs, dancing the dances, telling the stories, painting the Songlines and Dreamings.

The creation was believed to be the work of culture heroes that in the creative epoch travelled across a formless land, creating sacred sites and significant places of interest in their travels. In this way songlines were established, some of which could travel right across Australia, through as many as six to ten different language groupings. The songs and dances of a particular songline were kept alive and frequently performed at large gatherings, organised in good seasons.

In the Aboriginal world view, every event leaves a record in the land. Everything in the natural world is a result of the actions of the archetypal beings, beings whose actions created the world. Whilst Europeans consider these cultural ancestors to be magical many Aboriginal people still believe in their literal existence. The meaning and significance of particular places and creatures is wedded to their origin in the Dreaming, and certain places have a particular potency, which the Aborigines call its dreaming. In this dreaming resides the sacredness of the earth. For example in Perth, the Noongar believe that the Darling Scarp is said to represent the body of a Wagyl - a serpent being that meandered over the land creating rivers, waterways and lakes. It is taught that the Wagyl created the Swan River.

In one version (there are many Aboriginal cultures) Altjira was the god of the Dreamtime; he created the Earth and then retired as the Dreamtime vanished. Alternative names for Aktjira in other Australian languages include Alchera (Arrernte), Alcheringa, Mura-mura (Dieri), and Tjukurpa (Pitjantjatjara).

The dreaming and travelling trails of the Spirit Beings are the songlines (or "Yiri" in the Warlpiri language). The signs of the Spirit Beings may be of spiritual essence, physical remains such as petrosomatoglyphs of body impressions or footprints, amongst natural and elemental simulacrae. To cite an example, the Yarralin people of the Victoria River Valley venerate the spirit Walujapi as the Dreaming Spirit of the black-headed python. Walujapi carved a snakelike track along a cliff-face and deposited an impression of her buttocks when she sat establishing camp. Both these dreaming signs are currently discernible.

Wandjina They resemble Gray Aliens

In Aboriginal mythology, the Wondjina (or wandjina) were cloud and rain spirits who, during the Dream time, painted their images (as humans but without mouths) on cave walls. It has been said if they had mouths, the rain would never cease. They also lacked limbs and had a skull-like face. Their ghosts still exist in small ponds. Walaganda, one of the Wondjina, became the Milky Way. Paintings of this style that represent the mythological beings involved in the creation of the world are called "Wondjina style".

The Wandjinas have common colors of black, red and yellow on a white background. Wandjinas are believed to have made the sea, the earth and all its inhabitants. The existing rock art found, has depicted them as having huge upper bodies and large heads. Their faces show eyes and nose, but typically lack mouths. Around the heads of Wandjinas there appears to be lightning and feathers. The Wandjina is thought to have special powers and if offended, can cause flooding and intense lightning. The paintings are still believed to have special powers and therefore are to be approached cautiously.

An Australian Aboriginal Legend

And again like the Lord God, Baiame walked on the earth he had made, among the plants and animals, and created man and woman to rule over them. He fashioned them from the dust of the ridges, and said, 'These are the plants you shall eat - these and these, but not the animals I have created.'

Having set them in a good place, the All-Father departed.

To the first man and woman, children were born and to them in turn children who enjoyed the work of the hands of Baiame. His world had begun to be populated, and men and women praised Baiame for providing for all their needs. Sun and rain brought life to the plants that provided their sustenance.

All was well in the world they had received from the bountiful provider, until a year when the rain ceased to fall. There was little water. The flowers failed to fruit, leaves fell from the dry, withered stems, and there was hunger in the land--a new and terrifying experience for men, women, and little children who had never lacked for food and drink.

In desperation a man killed some of the forbidden animals, and shared the kangaroo-rats he had caught with his wife. They offered some of the flesh to one of their friends but, remembering Baiame's prohibition, he refused it. The man was ill with hunger. They did their best to persuade him to eat, but he remained steadfast in his refusal. At length, wearying of their importunity, he staggered to his feet, turning his back on the tempting food, and walked away.

Shrugging their shoulders, the husband and wife went on with their meal. Once they were satisfied, they thought again of their friend and wondered whether they could persuade him to eat. Taking the remains of the meal with them, they followed his trail. It led across a broad plain and disappeared at the edge of a river. They wondered how he had crossed it and, more importantly, how they themselves could cross. In spite of the fact that it had dwindled in size, owing to the prolonged drought, it was running too swiftly for them to wade or swim.

They could see him, some little distance away on the farther side, lying at the foot of a tall gum tree. They were on the point of turning back when they saw a coal-black figure, half man half beast, dropping from the branches of the tree and stooping over the man who was lying there. They shouted a warning, but were too far away for him to hear, even if he were awake. The black monster picked up the inert body, carried it up into the branches and disappeared. They could only think that the tree trunk was hollow and that the monster had retreated to its home with his lifeless burden.

One event succeeded another with bewildering rapidity. A puff of smoke billowed from the tree. The two frightened observers heard a rending sound as the tree lifted itself from the ground, its roots snapping one by one, and soared across the river, rising as it took a course to the south. As it passed by they had a momentary glimpse of two large, glaring eyes within its shadow, and two white cockatoos with frantically flapping wings, trying to catch up with the flying tree, straining to reach the shelter of its branches.

Within minutes the tree, the cockatoos, and the glaring eyes had dwindled to a speck, far to the south, far above their heads,For the first time since creation, death had come to one of the men whom Baiame had created, for the monster within the tree trunk was Yowee, the Spirit of Death.

In the desolation of a drought-stricken world, all living things mourned because a man who was alive was now as dead as the kangaroo-rats that had been killed for food.

Baiame's intention for the men and animals he loved had been thwarted. 'The swamp oak trees sighed incessantly, the gum trees shed tears of blood, which crystalized as red gum,' wrote Roland Robinson, in relating this legend of the Kamilroi tribe in his book Wandjina. 'To this day,' he continued, 'to the tribes of that part is the Southern Cross known as "Yaraandoo"--the place of the White Gum tree--and the Pointers as "Mouyi", the white cockatoos.'

It was a sad conclusion to the hopes of a world in the making, but the bright cross of the Southern Cross is a sign to men that there is a place for them in the limitless regions of space, the home of the All-Father himself, and that beyond death lies a new creation.

Blue Mountains

According to an Aboriginal dreamtime story, the three huge rocks formation were once three beautiful sisters named "Meehni", "Wimlah" and "Gunnedoo" from the Katoomba tribe. The three sisters fell in love with three brothers from the Nepean tribe but their tribal laws forbade their marriage. The three brothers did not accept this law and tried to capture the three sisters by force. This caused a major tribal battle and the lives of the three sisters were thus threatened. A witchdoctor decided to turn the sisters into rocks in order to protect them and thought to reverse the spell only after the battle. Unfortunately, he was killed in the battle and the three sisters remained as the enormous and beautiful rock formations until today. The magnificent formation stands at 922m, 918m, and 906m respectively.

There was a time when everything was still. All the spirits of the earth were asleep - or almost all. The great Father of All Spirits was the only one awake. Gently he awoke the Sun Mother. As she opened her eyes a warm ray of light spread out towards the sleeping earth. The Father of All Spirits said to the Sun Mother, "Mother, I have work for you. Go down to the Earth and awake the sleeping spirits. Give them forms."

The Sun Mother glided down to Earth, which was bare at the time and began to walk in all directions and everywhere she walked plants grew. After returning to the field where she had begun her work the Mother rested, well pleased with herself. The Father of All Spirits came and saw her work, but instructed her to go into the caves and wake the spirits.

This time she ventured into the dark caves on the mountainsides. The bright light that radiated from her awoke the spirits and after she left insects of all kinds flew out of the caves. The Sun Mother sat down and watched the glorious sight of her insects mingling with her flowers. However once again the Father urged her on.

The Mother ventured into a very deep cave, spreading her light around her. Her heat melted the ice and the rivers and streams of the world were created. Then she created fish and small snakes, lizards and frogs. Next she awoke the spirits of the birds and animals and they burst into the sunshine in a glorious array of colors. Seeing this the Father of All Spirits was pleased with the Sun Mother's work.

She called all her creatures to her and instructed them to enjoy the wealth of the earth and to live peacefully with one another. Then she rose into the sky and became the sun.

The living creatures watched the Sun in awe as she crept across the sky, towards the west. However when she finally sunk beneath the horizon they were panic-stricken, thinking she had deserted them. All night they stood frozen in their places, thinking that the end of time had come. After what seemed to them like a lifetime the Sun Mother peeked her head above the horizon in the East. The earth's children learned to expect her coming and going and were no longer afraid.

At first the children lived together peacefully, but eventually envy crept into their hearts. They began to argue. The Sun Mother was forced to come down from her home in the sky to mediate their bickering. She gave each creature the power to change their form to whatever they chose. However she was not pleased with the end result. The rats she had made had changed into bats; there were giant lizards and fish with blue tongues and feet. However the oddest of the new animals was an animal with a bill like a duck, teeth for chewing, a tail like a beavers and the ability to lay egg. It was called the platypus.

The Sun Mother looked down upon the Earth and thought to herself that she must create new creatures less the Father of All Spirits be angered by what she now saw. She gave birth to two children. The god was the Morning Star and the goddess was the moon. Two children were born to them and these she sent to Earth. They became our ancestors. She made them superior to the animals because they had part of her mind and would never want to change their shape.

Once, the earth was completely dark and silent; nothing moved on its barren surface. Inside a deep cave below the Nullabor Plain slept a beautiful woman, the Sun. The Great Father Spirit gently woke her and told her to emerge from her cave and stir the universe into life. The Sun Mother opened her eyes and darkness disappeared as her rays spread over the land; she took a breath and the atmosphere changed; the air gently vibrated as a small breeze blew.

The Sun Mother then went on a long journey; from north to south and from east to west she crossed the barren land. The earth held the seed potencies of all things, and wherever the Sun's gentle rays touched the earth, there grasses, shrubs and trees grew until the land was covered in vegetation. In each of the deep caverns in the earth, the Sun found living creatures which, like herself, had been slumbering for untold ages She stirred the insects into life in all their forms and told them to spread through the grasses and trees, then she woke the snakes, lizards, and other reptiles, and they slithered out of their deep hold.

As the snakes moved through and along the earth they formed rivers, and they themselves became creators, like the Sun. Behind the snakes mighty rivers flowed, teeming with all kinds of fish and water life. Then she called for the animals, the marsupials, and the many other creatures to awake and make their homes on the earth.

The Sun Mother then told all the creatures that the days would from time to time change from wet to dry and from cold to hot, and so she made the seasons. One day while all the animals, insects and other creatures were watching, the Sun travelled far in the sky to the west and, as the sky shone red, she sank from view and darkness spread across the land once more. The creatures were alarmed and huddled together in fear. Some time later, the sky began to glow on the horizon to the east and the Sun rose smiling into the sky again. The Sun Mother thus provided a period of rest for all her creatures by making this journey each day.

For a long time there was no sun, only a moon and stars. That was before there were men on the earth, only birds and beasts, all of which were many sizes larger than they are now.

One day Dinewan the emu and Brolga the native companion were on a large plain near the Murrumbidgee. There they were, quarrelling and fighting. Brolga, in her rage, rushed to the nest of Dinewan and seized from it one of the huge eggs, which she threw with all her force up to the sky. There it broke on a heap of firewood, which burst into flame as the yellow yolk spilled all over it, and lit up the world below to the astonishment of every creature on it. They had been used to the semi-darkness and were dazzled by such brightness.

A good spirit who lived in the sky saw how bright and beautiful the earth looked when lit up by this blaze. He thought it would be a good thing to make a fire every day, and from that time he has done so. All night he and his attendant spirits collect wood and heap it up. When the heap is nearly big enough they send out the morning star to warn those on earth that the fire will soon be lit.

The spirits, however, found this warning was not sufficient, for those who slept saw it not. Then the spirits thought someone should make some noise at dawn to herald the coming of the sun and waken the sleepers. But for a long time they could not decide to whom should be given this office.

At last one evening they heard the laughter of Goo-goor-gaga, the laughing jackass, ringing through the air. "That is the noise we want," they said.

Then they told Goo-goor-gaga that, as the morning star faded and the day dawned, he was every morning to laugh his loudest, that his laughter might awaken all sleepers before sunrise. If he would not agree to do this, then no more would they light the sun-fire, but let the earth be ever in twilight again.

But Goo-goor-gaga saved the light for the world.

He agreed to laugh his loudest at every dawn of every day, and so he has done ever since, making the air ring with his loud cackling, "Goo goor gaga, goo goor gaga, goo goor gaga."

When the spirits first light the fire it does not throw out much heat. But by the middle of the day, when the whole heap of firewood is in a blaze, the heat is fierce. After that it begins to die gradually away until, at sunset, only red embers are left. They quickly die out, except a few the spirits cover up with clouds and save to light the heap of wood they get ready for the next day.

Children are not allowed to imitate the laughter of Goo-goor-gaga, lest he should hear them and cease his morning cry.

If children do laugh as he does, an extra tooth grows above their eye-tooth, so that they carry the mark of their mockery in punishment for it. Well the good spirits know that if ever a time comes when the Goo-goor-gagas cease laughing to herald the sun, then no more dawns will be seen in the land, and darkness will reign once more.

Once upon a time the whole country was flat. There were no hills at all. There was a buck kangaroo called Urdlu and a buck euro called Mandya who both lived in the plains called Puthadamathanha. These two used to travel around together in the same country. One of their favourite foods was the wild pear root. In fact, it was they who gave it its name ngarndi wari.

Urdlu the kangaroo and Mandya the euro dug for tucker in separate holes. Urdlu found a lot of tucker, but Mandya found only a little. Urdlu, however, wouldn't tell Mandya where his hole was. Poor Mandya was getting thinner and thinner and Urdlu was getting fatter and fatter. In the end Mandya came to Urdlu and said: "Give me some of your mai" (mai is tucker). Urdlu said to Mandya: "There's some mai in that bag there. You can take that." As he ate it, Mandya said, "This is really good tucker! Where did you get it?" Urdlu said with a wave of his arm, "Oh, I found it over there."

The pair of them went to sleep. In the morning Urdlu got up and went to look for water. While he went around looking here and there for water to drink, Mandya got up and went to find the hole where Urdlu got his tucker. He picked up Urdlu's tracks and followed them. He went along steadily down the track made by the kangaroo until he came to his hole. He dug out a big heap of tucker from it. He was so pleased he stayed there digging and eating without even looking up.

Urdlu came back from having a drink. "Now where on earth has the old fellow got to? I know, he's gone to my hole!" He took off after Mandya. He tracked him. His fresh tracks were there, all the way down to the hole. He could see where Mandya had dug up the dirt as he went along. He sure had dug up the dirt! When Urdlu arrived at the hole Mandya was so busy digging he didn't even see Urdlu coming. Mandya was digging like mad. Urdlu called out, "Why did you come to my hole?" Mandya said he was starving and Urdlu was mean not to tell him where there was tucker. He just went on eating. Now this made Urdlu really angry, so the pair of them were soon having a big fight, all over tucker. Mandya pulled at Urdlu's arms. He stretched his arms, he stretched his fingers, he stretched his legs. They got very long. Then Urdlu pressed Mandya's fingers and his legs; he pressed his back, his chest; he thrashed him. Then they separated.

The wounded Mandya went off to Vadaardlanha to camp. While he was lying there trying to go to sleep, his hip started to hurt. In fact, he had a sore. He reached down and took out a little stone from the sore. He blew on it and in a flash hills came up from the plain. Indeed, several ranges of hills came up. The more Mandya blew, the more hills kept coming up.

Meanwhile Urdlu headed down towards Varaarta (Baratta). He moved that big flat (plain) along as he went. He was lying out there on the flat when he looked back and saw the hills coming down the plain. He said, "Hey! What's the old fellow up to? Over that way there's a big range of hills coming up! If he keeps that up I won't have anywhere to live!" So, with a big sweep of his tail Urdlu pushed the ranges back to where they are now. You can see where this happened, up there north of Vardna-wartathinha. That big flat never gets any grass on it. It's called Urdlurunha-vitana (kangaroo's flat).

Urdlu then made Munda (Lake Frome) so that he would have a permanent supply of water, but Mandya was jealous about this and put salt in it. Right to the present day kangaroos cannot drink from this lake because of the salt.

Mandya was up there in the hills behind Vadaardlanha. From there he looked back and said, "Look at the way the old fellow moved that big plain along!" And as Mandya looked back he turned into a spirit. He is called Thudupinha, and you can see him sitting up there today. Below him the ground is red where his wounds bled after his big fight with Urdlu. This place is called Mandya Arti (which means Mandya's blood).

Australian Dreamtime Google Videos

Australian Dreamtime Google Videos

Dreamtime Wikipedia

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS