Norse Mythology for Smart People provides reliable, well-documented information on the fascinating mythology and religion of the Norse/Germanic peoples. If that’s what you’re looking for, you’ve come to the right place.

What is Norse mythology?

Before the Norse (a.k.a. the Vikings) and other Germanic peoples were converted to Christianity during the Middle Ages, they had their own highly sophisticated and complex indigenous religion. Norse mythology is the set of religious stories the Vikings told to one another. These myths revolved around deities with fascinating and highly complex characters, such as Odin, Thor, Freya, and Loki.

The religion of the Norse and other Germanic peoples never had a true name – those who practiced it just called it “tradition.” However, people who continued to follow the old ways after the arrival of Christianity were sometimes called “heathens,” which originally meant simply “people who live on the heaths” or elsewhere in the countryside, and the name has stuck. Throughout this site, I refer to it as “the heathen Germanic religion,” “the pre-Christian Germanic religion,” or something to that effect.

Norse mythology was for the heathen Germanic peoples what the stories in the Bible are to Christians and what the doctrines of evolution and historical progress are to modern science and secular society: grand narratives that give life meaning and that help people to make sense of the world.

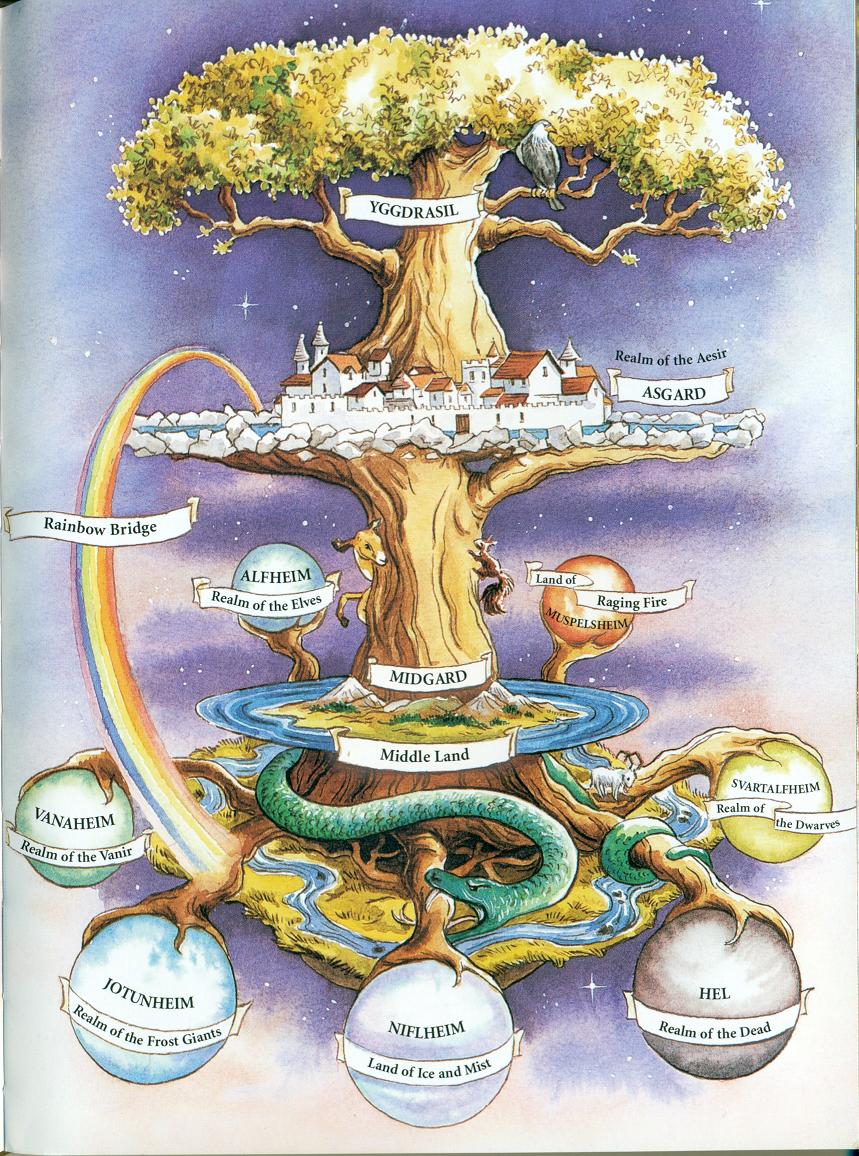

Ultimately, Norse mythology presents a worldview that is very, very different from the worldview of modern science or that of most modern “world religions.” The pre-Christian Germanic religion was animistic, polytheistic, pantheistic, and held a cyclical view of time.

Who were the Vikings?

The Vikings were seafaring warriors, raiders, and explorers from modern-day Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland who ventured throughout much of the world during the Viking Age (roughly 793-1066 CE). They traveled as far east as Constantinople and as far west as North America in search of riches to plunder and fertile lands in which to settle. They spoke the Old Norse language, wrote in runes, and practiced their ancestral religion.

The reasons behind Viking raids and settlements during this period are numerous and include population pressures, demographic changes, the high value placed on honor and competitive accomplishments in traditional Germanic society, and a desire to retaliate against the violent incursions of Christianity amongst the Norse and other Germanic peoples that were occurring throughout the Viking Age.

The Vikings are an important part of the study of the indigenous mythology and religion of the Germanic peoples because the vast majority of what we know about these topics comes from Scandinavian and Icelandic poems, treatises, and sagas that were written during or relatively soon after the Viking Age.

Who are the Germanic peoples?

The Germanic peoples are one of the indigenous peoples of northern Europe, along with the Celts, Sami, Finns, and others. Historically, they’ve occupied much of Scandinavia, Iceland, the British Isles, and continental Europe north of the Alps. In the modern era, they’re spread out across the world.

While there were certainly regional and temporal variations in the pre-Christian religion of the Germanic peoples, there was nevertheless a common core worldview, cosmology, and, to a large extent, a common pantheon as well.

If you’re a person of northern European descent (including English and German descent), it’s a safe bet that you’ve got some Germanic blood in you. That means, in turn, that it’s a safe bet that some of your ancestors practiced something very, very close to the religion represented by Norse mythology.

Of course, you very well may still find Norse/Germanic mythology to be fascinating and illuminating if you don’t have any Germanic in your ancestry. Mythologies are certainly expressions of a particular person or people, but they’re far from only that; there tends to be a spark of something more timeless and universal in them as well.

Til árs ok friðar,

Daniel McCoy