Proto-Indo-European religion

Trundholm sun chariot pictured, Nordic Bronze Age, c. 1600 BC

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Philology[show]

|

|

Origins[show]

|

|

Archaeology[show]

|

|

Peoples and societies[show]

|

|

Religion and mythology[show]

|

Proto-Indo-European religion is the belief system adhered to by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. Although this belief system is not directly attested, it has been reconstructed by scholars of comparative mythology based on the similarities in the belief systems of various Indo-European peoples.

Various schools of thought exist regarding the precise nature of Proto-Indo-European religion, which do not always agree with each other. Vedic mythology, Roman mythology, and Norse mythology are the main mythologies normally used for comparative reconstruction, though they are often supplemented with supporting evidence from the Baltic, Celtic, Greek, Slavic, and Hittite traditions as well.

The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes well-attested deities such as *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, the god of the daylit skies, his daughter *Haéusōs, the goddess of the dawn, the Horse Twins, and the storm god *Perkwunos. Other probable deities include *Péh2usōn, a pastoral god, and *Seh2ul, a Sun goddess.

Well-attested myths of the Proto-Indo-Europeans include a myth involving a storm god who slays a multi-headed serpent that dwells in water, a myth about the Sun and Moon riding in chariots across the sky, and a creation story involving two brothers, one of whom is sacrificed by the other in order to create the world. The Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that the Otherworld was guarded by some kind of watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river. They also may have believed in some kind of world tree, bearing fruit of immortality, either guarded by or gnawed on by a serpent or dragon of some kind and tended to by three goddesses, who were believed to spin the thread of life.

Contents

[hide]

Methods of reconstruction[edit]

Schools of thought[edit]

Georges Dumézil, formulator of the Trifunctional Hypothesis

The religion of the Proto-Indo-Europeans is not directly attested and it is difficult to match their language to archaeological findings related to any specific culture from the Chalcolithic.[1] Nonetheless, scholars of comparative mythology have attempted to reconstruct aspects of Proto-Indo-European religion based on the existence of similarities among the deities, religious practices, and myths of various Indo-European peoples. This method is known as the comparative method. Different schools of thought have approached the subject of Proto-Indo-European religion from different angles. The Meteorological School holds that Proto-Indo-European religion was largely centered around deified natural phenomena such as the sky, the Sun, the Moon, and the dawn.[2] This meteorological interpretation was popular among early scholars, but has lost a considerable degree of scholarly support in recent years.[3] The Ritual School, on the other hand, holds that Proto-Indo-European myths are best understood as stories invented to explain various rituals and religious practices.[4] Bruce Lincoln, a member of the Ritual School, argues that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed that every sacrifice was a reenactment of the original sacrifice performed by the founder of the human race on his twin brother.[4] The Functionalist School holds that Proto-Indo-European society and, consequently, their religion, was largely centered around the trifunctional system proposed by Georges Dumézil,[5] which holds that Proto-Indo-European society was divided into three distinct social classes: farmers, warriors, and priests.[5][6] The Structuralist School, by contrast, argues that Proto-Indo-European religion was largely centered around the concept of dualistic opposition.[7] This approach generally tends to focus on cultural universals within the realm of mythology, rather than the genetic origins of those myths,[7] but it also offers refinements of the Dumézilian trifunctional system by highlighting the oppositional elements present within each function, such as the creative and destructive elements both found within the role of the warrior.[7]

Source mythologies[edit]

One of the earliest and most important of all Indo-European mythologies is Vedic mythology,[8] especially the mythology of the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. Early scholars of comparative mythology such as Max Müller stressed the importance of Vedic mythology to such an extent that they practically equated it with Proto-Indo-European myth.[9]Modern researchers have been much more cautious, recognizing that, although Vedic mythology is still central, other mythologies must also be taken into account.[9]

Another of the most important source mythologies for comparative research is Roman mythology.[8][10] Contrary to the frequent bald statement made by some authors that "Rome has no myth", the Romans possessed a very complex mythological system, parts of which have been preserved through the unique Roman tendency to rationalize their myths into historical accounts.[11] Despite its relatively late attestation, Norse mythology is still considered one of the three most important of the Indo-European mythologies for comparative research,[8] simply due to the vast bulk of surviving Icelandic material.[10]

Baltic mythology has also received a great deal of scholarly attention, but has so far remained frustrating to would-be researchers on account of the fact that the sources are so comparatively late.[12] Nonetheless, Latvian folk songs are seen as a major source of information in the process of reconstructing Proto-Indo-European myth.[13] Despite the popularity of Greek mythology in western culture,[14] Greek mythology is generally seen as having little importance in comparative mythology due to the heavy influence of Pre-Greek and Near Eastern cultures, which overwhelms what little Indo-European material can be extracted from it.[15] Consequently, Greek mythology received minimal scholarly attention until the mid 2000s.[8]

Pantheon[edit]

Linguists are able to reconstruct the names of some deities in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) from many types of sources. Some of the proposed deity names are more readily accepted among scholars than others.[Notes 1]

The term for "a god" was *deiwos,[16] reflected in Hittite, sius; Latin, deus, divus; Sanskrit, deva; Avestan, daeva (later, Persian, div); Welsh, duw; Irish, dia; Old Norse, tívurr; Lithuanian, Dievas; Latvian, Dievs.[17]

Heavenly deities[edit]

Sky Father[edit]

Laurel-wreathed head of Zeus on a gold stater from the Greek city of Lampsacus, c 360–340 BC

The supreme ruler of the Proto-Indo-European pantheon was the god *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, whose name literally means "Sky Father". He is believed to have been worshipped as the god of the daylit skies. He is, by far, the most well-attested of all the Proto-Indo-European deities. The Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter, and the Illyrian god Dei-Pátrous all appear as the head gods of their respective pantheons. The Norse god Týr, however, seems to have been demoted to the role of a minor war-deity during the time prior to the earliest Germanic texts.[18] *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr is also attested in the Rigveda as Dyáus Pitā, a minor ancestor figure mentioned in only a few hymns. The names of the Latvian god Dievs and the Hittite god Attas Isanus do not preserve the exact literal translation of the name *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, but do preserve the general meaning of it.[19]

*Dyḗus Pḥatḗr may have had a consort who was an earth goddess.[20] This possibility is attested in the Vedic pairing of Dyáus Pitā and Prithvi Mater,[20] the Roman pairing of Jupiter and Tellus Mater from Macrobius's Saturnalia,[20] and the Norse pairing of Odin and Jörð. Odin is not a reflex of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, but his cult may have subsumed aspects of an earlier chief deity who was.[21] This pairing may also be further attested in an Old English ploughing prayer[21] and in the Greek pairings of Ouranos and Gaia and Zeus and Demeter.[22]

Dawn Goddess[edit]

Eos in her chariot flying over the sea, red-figure krater from South Italy, 430–420 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlungen

*Haéusōs has been reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European goddess of the dawn. Derivatives of her found throughout various Indo-European mythologies include the Greek goddess Eos, the Roman goddess Aurōra, the Vedic goddess Uṣás, and the Lithuanian goddess Auštrine.[23] The form Arap Ushas appears in Albanian folklore, but as a name for the Moon, not the dawn. An extension of the name may have been *H2eust(e)ro-,[24] since the form *as-t-r with an intrusive -t- between s and r occurs in some northern dialects.[25][26]

Examples of such forms include the Anatolian Estan, Istanus, and Istara, the Greek Hestia, goddess of the hearth, the Latin Vesta, also a hearth goddess, the Armenian Astghik, a star goddess, the Baltic goddess Austija,[27] and possibly also the Germanic Ēostre or *Ostara, a goddess associated with a springtime festival who is mentioned only once by Bede in his treatise The Reckoning of Time.

Sun and Moon[edit]

Possible depiction of the Hittite Sun goddess holding a child in her arms from between 1400 and 1200 BC

*Seh2ul and *Meh1not are reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European goddess of the Sun and god of the Moon respectively. *Seh2ul is reconstructed based on the Greek god Helios, the Roman god Sol, the Celtic goddess Sul/Suil, the Norse goddess Sól, the Germanic goddess *Sowilō, the Celtic Sul, the Hittite goddess "UTU-liya",[28] and the Vedic god Surya.[29]

*Meh1not- is reconstructed based on the Norse god Máni, the Slavic god Myesyats,[28] and the Lithuanian god *Meno, or Mėnuo (Mėnulis).[30] They are often seen as the twin children of various deities,[31] but in fact the sun and moon were deified several times and are often found in competing forms within the same language.[31]

The usual scheme is that one of these celestial deities is male and the other female, though the exact gender of the Sun or Moon tends to vary among subsequent Indo-European mythologies.[31] The original Indo-European solar deity appears to have been female,[31] a characteristic not only supported by the higher number of sun goddesses in subsequent derivations (feminine Sól, Saule, Sulis, Solntse—not directly attested as a goddess, but feminine in gender — Étaín, Grían, Aimend, Áine, and Catha versus masculine Helios, Surya, Savitr, Usil, and Sol) (Hvare-khshaeta is of neutral gender),[31] but also by vestiges in mythologies with male solar deities (Usil in Etruscan art is depicted occasionally as a goddess, while solar characteristics in Athena and Helen of Troy still remain in Greek mythology).[31] The original Indo-European lunar deity appears to have been masculine,[31] with feminine lunar deities like Selene, Minerva, and Luna being a development exclusive to the eastern Mediterranean. Even in these traditions, remnants of male lunar deities, like Menelaus, remain.[31]

Although the sun was personified as an independent, female deity, the Proto-Indo-Europeans also visualized the sun as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr, as seen in various reflexes: Helios as the eye of Zeus,[32][33]Hvare-khshaeta as the eye of Ahura Mazda, and the sun as "God's eye" in Romanian folklore.[34] The names of Celtic sun goddesses like Sulis and Grian may also allude to this association; the words for "eye" and "sun" are switched in these languages, hence the name of the goddesses.[35][31]

Divine Twins[edit]

Horse Twins[edit]

Pair of Roman statuettes from the third century AD depicting the Dioscuri as horsemen, with their characteristic skullcaps (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Horse Twins are a set of twin brothers found throughout nearly every Indo-European pantheon who usually have a name that means 'horse' *ekwa-, but the names are not always cognate and no Proto-Indo-European name for them can be reconstructed.[36] In most Indo-European pantheons, the Horse Twins are brothers of the Sun Maiden or Dawn goddess, and sons of the sky god.[37]

They are reconstructed based on the Vedic Ashvins, the Lithuanian Ašvieniai, the Latvian Dieva deli, the Greek Dioskouroi (Kastor and Polydeukes), the Roman Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux), the Irish twins of Macha, the Old English Hengist and Horsa (whose names mean "stallion" and "horse"), the Slavic Lel and Polel (possibly Christianized in Albanian as saints Flori and Lori) and possibly Old Norse Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse born of Loki. The horse twins may have been based on the morning and evening star (the planet Venus) and they often have stories about them in which they "accompany" the Sun goddess, because of the close orbit of the planet Venus to the sun.[38]

Twin Founders[edit]

The Proto-Indo-European Creation myth seems to have involved two key figures: *Manu- ("Man"; Indic Manu; Germanic Mannus) and *Yemo- ("Twin"; Indic Yama; Germanic Ymir), his twin brother. Reflexes of these two figures usually fulfill the respective roles of founder of the human race and first human to die.[39][40]

Storm deities[edit]

Ancient Celtic statue of the storm-god Taranis, clutching a wheel and thunderbolt, from Le Chatelet, Gourzon, Haute-Marne, France

*Perkwunos has been reconstructed as the Proto-Indo-European god of lightning and storms. His name literally means "The Striker." He is reconstructed based on the Norse goddess Fjǫrgyn (the mother of Thor), the Lithuanian god Perkūnas, and the Slavic god Perúnú. The Vedic god Parjánya may also be related, but his possible connection to *Perkwunos is still under dispute.[41] The name of *Perkwunosmay also be attested in Greek as κεραυνός (Keraunós), an epithet of the god Zeus meaning "thunder-shaker."[42]

Water deities[edit]

Some authors have proposed *Neptonos or *H2epom Nepōts as the Proto-Indo-European god of the waters. The name literally means "Grandson [or Nephew] of the Waters." He has been reconstructed based on the Vedic god Apám Nápát, the Roman god Neptūnus, and the Old Irish god Nechtain. Although such a god has been solidly reconstructed in Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, Mallory and Adams nonetheless still reject him as a Proto-Indo-European deity on linguistic grounds.[43]

A river goddess *Dehanu- has been proposed based on the Vedic goddess Dānu, the Irish goddess Danu, the Welsh goddess Don and the names of the rivers Danube, Don, Dnieper, and Dniester. Mallory and Adams, however, dismiss this reconstruction, commenting that it does not have any evidence to support it.[44]

Some have also proposed the reconstruction of a sea god named *Trihatōn based on the Greek god Triton and the Old Irish word trïath, meaning "sea." Mallory and Adams reject this reconstruction as having no basis, asserting that the "lexical correspondence is only just possible and with no evidence of a cognate sea god in Irish."[44]

Nature deities[edit]

*Péh2usōn, a pastoral deity, is reconstructed based on the Greek god Pan and the Vedic god Pūshān. Both deities are closely affiliated with goats and were worshipped as pastoral deities.[47] The minor discrepancies between the two deities can be easily explained by the possibility that many attributes originally associated with Pan may have been transferred over to his father Hermes.[47] The association between Pan and Pūshān was first identified in 1924 by the German scholar Hermann Collitz.[48][49]

In 1855, Adalbert Kuhn suggested that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed in a set of helper deities, whom he reconstructed based on the Germanic elves and the Hindu rhibus.[50][51] Though this proposal is often mentioned in academic writings, very few scholars actually accept it.[52] There may also have been a female cognate akin to the Greco-Roman nymphs, Slavic vilas, the Huldra of Germanic folklore, and the Hindu Apsaras.[53]

Societal deities[edit]

It is highly probable that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed in three fate goddesses who spun the destinies of mankind. Although such fate goddesses are not directly attested in the Indo-Aryan tradition, the Atharvaveda does contain an allusion comparing fate to a warp.[54] Furthermore, the three Fates appear in nearly every other Indo-European mythology.[54] Examples include the Hittite Gulses, the Greek Moirai, the Roman Parcae, the Norse Norns, the Lithuanian Deivės Valdytojos, the Latvian Láimas, the Serbian Sudjenice, and the Albanian Fatit.[55] They appear in English mythology as the Wyrdes,[56] who were later adapted to become the Three Witches in Shakespeare's Macbeth.[57] An Old Irish hymn attests to seven goddesses who were believed to weave the thread of destiny, which demonstrates that these spinster fate-goddesses were present in Celtic mythology as well.[58]

Depiction of Wayland the Smith from the Franks Casket, dating to the eighth century AD

Although the name of a particular Proto-Indo-European smith god cannot be linguistically reconstructed,[59] it is highly probable that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had a smith deity of some kind since smith gods occur in nearly every Indo-European culture, with examples including the Hittite god Hasammili, the Vedic god Tvastr, the Greek god Hephaestus, the Germanic villain Wayland the Smith, and the Ossetian culture figure Kurdalagon.[60] Many of these smith figures share certain characteristics in common. Hephaestus, the Greek god of blacksmiths, and Wayland the Smith, a nefarious blacksmith from Germanic mythology, are both described as lame.[61] Additionally, Wayland the Smith and the Greek mythical inventor Daedalus both escape imprisonment on an island by fashioning sets of mechanical wings from feathers and wax and using them to fly away.[62]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans may have had a goddess who presided over the trifunctional organization of society. Various epithets of the Iranian goddess Anahita and the Roman goddess Juno provide sufficient evidence to solidly attest that she was probably worshipped, but no specific name for her can be lexically reconstructed.[63] Vague remnants of this goddess may also be preserved in the Greek goddess Athena.[64]

Some scholars have proposed a war god *Māwort- based on the Roman god Mars and the Vedic Marutás, companions of the war-god Indra. Mallory and Adams, however, reject this reconstruction on linguistic grounds.[65]

Mythology[edit]

Dragon or serpent[edit]

The Hittite god Tarhunt, followed by his son Sarruma, kills the dragon Illuyanka (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey)

One common myth among almost all Indo-European mythologies is a battle ending with a hero or god slaying a serpent or dragon of some sort.[66] Although the details of story often vary widely, in all iterations, several features often remain remarkably the same. In all iterations of the story, the serpent is always associated with water in some way. The hero of the story is usually a thunder-god or a hero who is somehow associated with thunder. The serpent is usually multi-headed, or else "multiple" in some other way.[67]

The earliest attested of these stories is the legend from Hittite mythology in which the storm god Tarhunt slays the giant serpent Illuyanka.[68] Next oldest is the account recorded in the Rigveda in which the god Indra slays the multi-headed serpent Vritra, which had been causing a drought.[69] In the Bhagavata Purana, Krishna slays the serpent Kāliyā.

Greek red-figure vase painting depicting Heracles slaying the Lernaean Hydra, c. 375–340 BC

Several variations of the story are also found in Greek mythology as well. The story is attested in the legend of Zeus slaying the hundred-headed Typhon from Hesiod's Theogony, but it is also in the myths of the slaying of the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra by Heracles and the slaying of Python by Apollo.[67] The story of Heracles's theft of the cattle of Geryon is probably also related.[67]Although Heracles is not usually thought of as a storm deity in the conventional sense, he bears many attributes held by other Indo-European storm deities, including physical strength and a knack for violence and gluttony.[67]

The original Proto-Indo-European myth is also reflected in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, Thor, the god of thunder, slays the giant serpent Jörmungandr, which lived in the waters surrounding the realm of Midgard.[70] Other dragon-slaying myths are also found in the Germanic tradition. In the Völsunga saga, Sigurd slays the dragon Fafnir and, in Beowulf, the eponymous hero slays a different dragon.

Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European dragon-slaying myth are found throughout other branches of the language family as well. In Zoroastrianism and Persian mythology, Fereydun, and later Garshasp, slays Zahhak.[71] In Slavic mythology, Perun, the god of storms, slays Veles and Dobrynya Nikitich slays the three-headed dragon Zmey. In Armenian mythology, the god Vahagn slays the dragon Vishap.[72] In Romanian folklore, Făt-Frumos slays the fire-spitting monster Zmeu. In Celtic mythology, Dian Cecht slays Meichi.

The myth is believed to have symbolized a clash between forces of order and chaos.[66] In every version of the story, the dragon or serpent always loses, although in some mythologies, such as the NorseRagnarök myth, the hero or god dies as well. The Proto-Indo-European name for the serpent may have been *kʷr̥mis, or some name cognate with *Varuna/Werunos or the root *Wel/Vel- (VS Varuna, who is associated with the serpentine naga, Vala and Vṛtra, Slavic Veles, Baltic velnias), or "serpent" (Hittite Illuyanka, VS Ahis, Iranian azhi, Greek ophis and Ophion, and Latin anguis), or the root *dheubh- (Greek Typhon and Python).

Sun[edit]

Related to the dragon-slaying myth is the "Sun in the rock" myth, in which the Sun is imprisoned within a rock, but is set free by a heroic warrior deity, who splits open the rock, allowing her to escape. In the Rigveda, the goddess Ushas and a herd of cows are freed from imprisonment after the god Indra slays the multi-headed serpent Vritra.[73] A comparable myth in the Greek tradition is the myth of Aphroditerising from the foam of the sea following Ouranos's castration by Kronos.[73]

The Greek Sun-god Helios, the Hindu god Surya, and the Germanic goddess Sól are all represented as riding in chariots pulled by white horses. The earliest discovered chariots come from the Kurgan culture in southwest Russia, commonly identified as belonging to the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[74]

The myth of the Sun and Moon being swallowed by some kind of predator is also found throughout multiple Indo-European language groups. In Norse mythology, the Sun goddess (Sól) and Moon god (Máni) are swallowed by the wolves Sköll and Hati Hróðvitnisson.[75] In Hinduism, the Sun god (Surya) and Moon god (Chandra) are swallowed by the demon serpents Rahu and Ketu, resulting in eclipses.[76]

Twin founders[edit]

The analysis of different Indo-European tales indicates that the Proto-Indo-Europeans believed there were two progenitors of mankind: *Manu- ("Man") and *Yemo- ("Twin"), his twin brother. A reconstructed creation myth involving the two is given by David W. Anthony, attributed in part to Bruce Lincoln:[77] Manu and Yemo traverse the cosmos, accompanied by the primordial cow, and finally decide to create the world. To do so, Manu sacrifices either Yemo or the cow, and with help from the sky father, the storm god and the divine twins, forges the earth from the remains. Manu thus becomes the first priest and establishes the practice of sacrifice. The sky gods then present cattle to the third man, *Trito, who loses it to the three-headed serpent *Ngwhi, but eventually overcomes this monster either alone or aided by the sky father. Trito is now the first warrior and ensures that the cycle of mutual giving between gods and humans may continue.[77] Reflexes of *Manu include Indic Manu, Germanic Mannus; of Yemo, Indic Yama, Avestan Yima, Norse Ymir, possibly Roman Remus (< earlier Old Latin *Yemos).[77]

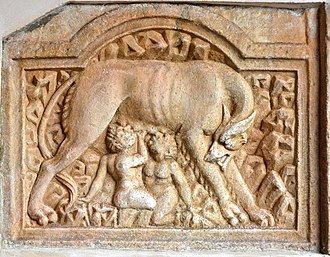

Ancient Roman relief from the Cathedral of Maria Saalshowing the infant twins Romulus and Remus being suckled by a she-wolf

The early "history" of Rome is widely recognized as a historicized retelling of various old myths.[78] Romulus and Remus are twin brothers from Roman mythology who both have stories in which they are killed.[79] The Roman writer Livy reports that Remus was believed to have been killed by his brother Romulus at the founding of Rome when they entered into a disagreement about which hill to build the city on. Later, Romulus himself is said to have been torn limb-from-limb by a group of senators.[Notes 2] Both of these myths are widely recognized as historicized remnants of the Proto-Indo-European creation story.[80]

The Germanic languages have information about both Ymir and Mannus (reflexes of *Yemo- and *Manu- respectively),[81] but they never appear together in the same myth. Instead, they only occur in myths widely separated by both time and circumstances.[81] In chapter two of his book Germania, which was written in Latin in around 98 A.D., the Roman writer Tacitus claims that Mannus, the son of Tuisto, was the ancestor of the Germanic people.[81] This name never recurs anywhere in later Germanic literature, but one proposed meaning of the German tribal name Alamanni is "Mannus' own people" ("all-men" being another scholarly etymology).[82]

Fire in water[edit]

Another important possible myth is the myth of the fire in the waters, a myth which centers around the possible deity *H2epom Nepōts, a fiery deity who dwells in water.[83] In the Rigveda, the god Apám Nápát is envisioned as a form of fire residing in the waters.[84] In Celtic mythology, a well belonging to the god Nechtain is said to blind all those who gaze into it.[83] In an old Armenian poem, a small reed in the middle of the sea spontaneously catches fire and the hero Vahagn springs forth from it with fiery hair and a fiery beard and eyes that blaze as suns.[85] In a ninth-century Norwegian poem by the poet Thiodolf, the name sǣvar niþr, meaning "grandson of the sea," is used as a kenning for fire.[86] Even the Greek tradition contains possible allusions to the myth of a fire-god dwelling deep beneath the sea. The phrase "νέποδες καλῆς Ἁλοσύδνης," meaning "descendants of the beautiful seas," is used in The Odyssey 4.404 as an epithet for the seals of Proteus.[85]

Cosmology[edit]

Underworld[edit]

Attic red-figure lekythos attributed to the Tymbos painter showing Charonwelcoming a soul into his boat, c. 500-450 BC

Most Indo-European traditions contain some kind of Underworld or Afterlife. It is possible that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that, in order to reach the Underworld, one needed to cross a river, guided by an old man (*ĝerhaont-).[87] The Greek tradition of the dead being ferried across the river Styx by Charon is probably a reflex of this belief.[87] The idea of crossing a river to reach the Underworld is also present throughout Celtic mythologies.[88] Several Vedic texts contain references to crossing a river in order to reach the land of the dead and the Latin word tarentum meaning "tomb" originally meant "crossing point."[89] In Norse mythology, Hermóðr must cross a bridge over the river Giöll in order to reach Hel.[90] In Latvian folk songs, the dead must cross a marsh rather than a river.[91] Traditions of placing coins on the bodies of the deceased in order to pay the ferryman are attested in the ancient Greek religion, but in the Slavic tradition as well.[88] It is also possible that the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed that the Underworld was guarded by some kind of watchdog, similar to the Greek Cerberus, the Hindu Śárvara, or the Norse Garmr.[87][92]

World tree and serpent[edit]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans may have believed in some kind of world tree.[93] It is also possible that they may have believed that this tree was either guarded by or under constant attack from some kind of dragon or serpent.[93] In Norse mythology, the world ash tree Yggdrasil is tended by the three Norns while the dragon Nidhogg gnaws at its roots.[93] In Greek mythology, the tree of the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides is tended by the three Hesperides and guarded by the hundred-headed dragon Ladon.[94] In Indo-Iranian texts, there is a mythical tree dripping with Soma, the immortal drink of the gods and, in later Pahlavi sources, an evil lizard is said to lurk at the bottom of it.[93]

Ritual and sacredness[edit]

Ancient Greek vase red-figure pot painting depicting two men sacrificing a pig to Demeter

Émile Benveniste states that "there is no common [IE] term to designate religion itself, or cult, or the priest, not even one of the personal gods".[95] There are, however, terms denoting ritual practice reconstructed in Indo-Iranian religion which have root cognates in other branches, hinting at common PIE concepts. Thus, the stem *hrta-, usually translated as "[cosmic] order" (Vedic ṛta and Iranian arta[96]). Benveniste states, "We have here one of the cardinal notions of the legal world of the Indo-Europeans, to say nothing of their religious and moral ideas" (pp. 379–381). He also adds that an abstract suffix -tu formed the Vedic stem ṛtu-, Avestan ratu- which designated order, particularly in the seasons and periods of time. The same root and suffix, but a different formation, appears in Latin rītus "rite".

Benveniste also posits the existence of a dual conception of sacredness, divided into a positive side, the intrinsic, otherworldly power of deities; and a negative side, sacredness of objects in the world that make them taboo for humans. This opposition is found in word pairs such as the Latin sacer/sanctus and Greek ἅγιος/ἱερός.[97]

See also[edit]

- Interpretatio graeca, the comparison of Greek deities to Germanic, Roman, and Celtic deities

- Neolithic religion

- Proto-Indo-European society

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ In order to present a consistent notation, the reconstructed forms used here are cited from Mallory & Adams 2006. For further explanation of the laryngeals – <h1>, <h2>, and <h3> – see the Laryngeal theory article.

- Jump up^ One of the original sources for the stories of Romulus and Remus is Livy's History of Rome, vol. 1, parts iv–vii and xvi. This has been published in an Everyman edition, translated by W. M. Roberts, E. P. Dutton & Co., New York 1912.

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 428.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, p. 14-15.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 429-430.

- Jump up^ Mythe et Épopée I, II, III, by G. Dumézil, Gallimard, 1995.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 431.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 440.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Puhvel 1987, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Puhvel 1987, p. 191.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 146–147.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 223–228.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 228–229.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, p. 126-127.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, p. 138, 143.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 408

- Jump up^ Indo-European *Deiwos and Related Words by Grace Sturtevant Hopkins (Language Dissertations published by the Linguistic Society of America, Number XII, December 1932)

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 198–200.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 409 and 431.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c West 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Jump up to:a b West 2007, p. 183.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 181–183.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 410 and 432.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 294, 301.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 702, 780.

- Jump up^ Gamkrelidze & Ivanov 1995.

- Jump up^ Noyer, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gamkrelidze & Ivanov 1995, p. 760

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 232.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 385.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Dexter 1984, pp. 137-144.

- Jump up^ Sick, David H. (2004), "Mit(h)ra(s) and the Myths of the Sun", Numen, 51 (4): 432–467, JSTOR 3270454

- Jump up^ Ljuba Merlina Bortolani, Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt: A Study of Greek and Egyptian Traditions of Divinity, Cambridge University Press, 13/10/2016

- Jump up^ Ionescu, Doina; Dumitrache, Cristiana (2012), "The Sun Worship with the Romanians." (PDF), Romanian Astronomical Journal, 22 (2): 155–166

- Jump up^ MacKillop, James. (1998). Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-280120-1 pp.10, 16, 128

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 432.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 185-191.

- Jump up^ Michael Shapiro. Journal of Indo-European Studies, 10 (1&2), pp. 137–166; who references D. Ward (1968) "The Divine Twins". Folklore Studies, No. 19. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Jump up^ Mallory 1987, p. 140.

- Jump up^ Lincoln 1991.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 410 and 433.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, p. 235.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 410.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 434.

- Jump up^ Taylor, Timothy (1992), “The Gundestrup cauldron”, Scientific American, 266: 84-89. ISSN 0036-8733

- Jump up^ Ross, Ann (1967), “The Horned God in Britain ”, Pagan Celtic Britain: 10-24. ISBN 0-89733-435-3

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 411 and 434.

- Jump up^ H. Collitz, "Wodan, Hermes und Pushan," Festskrift tillägnad Hugo Pipping pȧ hans sextioȧrsdag den 5 November 1924 1924, pp 574–587.

- Jump up^ Beekes, R. S. P., Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1149.

- Jump up^ Kuhn, Adalbert (1855). Die sprachvergleichung und die urgeschichte der indogermanischen völker. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 4., "Zu diesen ṛbhu, alba.. stellt sich nun aber entschieden das ahd. alp, ags. älf, altn . âlfr"

- Jump up^ in K. Z., p.110, Schrader, Otto (1890). Prehistoric Antiquities of the Aryan Peoples. Translated by Frank Byron Jevons. Charles Griffin & Company,. p. 163..

- Jump up^ Hall, Alaric (2007). Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity (PDF). Boydell Press. ISBN 1843832941.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 284–292.

- ^ Jump up to:a b West 2007, p. 380.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 379–385.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 382–383.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 383.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 384.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 410.

- Jump up^ West, 2009 & 154–157.

- Jump up^ West 2009.

- Jump up^ West 2009, p. 155.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams, p. 433.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 133–134.

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 2006, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Watkins 1995.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d West 2007, pp. 255–259.

- Jump up^ Philo Hendrik Jan Houwink Ten Cate: The Luwian Population Groups of Lycia and Cilicia Aspera During the Hellenistic Period. E. J. Brill, Leiden 1961, pp. 203–220.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 255–257.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 259.

- Jump up^ "IRAN iv. MYTHS AND LEGENDS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- Jump up^ Kurkjian 1958.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Michael Janda, Elysion. Entstehung und Entwicklung der griechischen Religion, (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, 2005), pp. 349–360; id., Die Musik nach dem Chaos: der Schöpfungsmythos der europäischen Vorzeit (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, 2010), 65.

- Jump up^ Anthony 2007, pp. 371–375.

- Jump up^ Sturluson 2006, p. 164.

- Jump up^ Charles Hartley. "Rahu & Ketu". Hartwick college, New York, USA. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Anthony 2007, pp. 134–135.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 144–165.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 286–287.

- Jump up^ Puhvel 1987, pp. 286–290.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Puhvel 1987, p. 285.

- Jump up^ Drinkwater, J. F. (25 January 2007), The Alamanni and Rome 213–496: (Caracalla to Clovis), OUP Oxford, pp. 63–69, ISBN 978-0-19-929568-5

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 438.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 270.

- ^ Jump up to:a b West 2007, p. 271.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 272.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 439.

- ^ Jump up to:a b West 2007, p. 390.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 389.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 390–391.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 391.

- Jump up^ West 2007, p. 392.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d West 2007, p. 346.

- Jump up^ West 2007, pp. 346–347.

- Jump up^ Indo-European Language and Society by Émile Benveniste (transl. by Elizabeth Palmer, pp. 445–6; orig. title Le vocabulaire des institutions Indo-Européennes, 1969), University of Miami Press, Coral Gables, Florida, 1973.

- Jump up^ Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1995 p. 810; c.f. Hittite ara, UL ara, DAra(a Hittite goddess).

- Jump up^ Mallory & Adams 1997, pp. 493-494.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Benveniste, Emile (1973), Indo-European Language and Society, translated by Palmer, Elizabeth, Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami Press, ISBN 978-0-87024-250-2

- Sturluson, Snorri (2006), The Prose Edda, translated by Byock, Jesse, Penguin Classics, p. 164, ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1984), "Proto-Indo-European Sun Maidens and Gods of the Moon", Mankind Quarterly, 25 (1 & 2): 137–144

- Frazer, James (1919), The Golden Bough, London: MacMillan

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, Vjaceslav V. (1995), Winter, Werner, ed., Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and a Proto-Culture, Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 80, Berlin: M. De Gruyter

- Grimm, Jacob (1966), Teutonic Mythology, translated by Stallybrass, James Steven, London: Dover, (DM)

- IRAN iv. MYTHS AND LEGENDS – Encyclopaedia Iranica, Iranicaonline.org, retrieved 2015-12-23

- Janda, Michael, Die Musik nach dem Chaos, Innsbruck 2010.

- Lincoln, Bruce (27 August 1991), Death, War, and Sacrifice: Studies in Ideology and Practice, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226482002

- Mallory, James P. (1991), In Search of the Indo-Europeans, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5, (EIEC)

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006), Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, London: Oxford University Press

- Noyer, Rolf, PIE Deities and the Sacred: Proto-Indo-European Language and Society (PDF), University of Pennsylvania, retrieved 28 February 2017

- Pleins, J. David (2010), When the Great Abyss Opened: Classic and Contemporary Readings of Noah's Flood, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 110, ISBN 978-0-19-973363-7, retrieved 6 April 2017

- Puhvel, Jaan (1987), Comparative Mythology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-3938-6

- Renfrew, Colin (1987), Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-European Origins, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-521-35432-5

- Shulman, David Dean (1980), Tamil Temple Myths: Sacrifice and Divine Marriage in the South Indian Saiva Tradition, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-5692-3

- Kurkjian, Vahan M., "History of Armenia: Chapter XXXIV", Penelope, University of Chicago, retrieved 6 April 2017

- Watkins, Calvert (1995), How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0

- West, Martin Litchfield (2007), Indo-European Poetry and Myth (PDF), Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9, retrieved 2 April 2017