Rough Notes:

Credit: Rens van der Sluijs |

||

|

pic of the day Links: Society for

|

May 24, 2005 The legend of the flood is one of the best known and most appealing genres of myth. During the past few centuries, missionaries and anthropologists have collected several hundreds of versions from all parts of the world. Even Africa and Australia, long thought to lack proper parallels to the deluge of Noah, have now been shown to have their share. Not all flood myths need to be related nor do they have to refer to the same event. What can be demonstrated, however, is that the earliest attested versions, originating in the ancient Near-East, derive from a common source and form a true literary tradition. These include the famous Greek myth of Deucalion, the Jewish account of Noah, and the Mesopotamian myths of Ut-Napishtim, Ziusudra, and Atrahasis. The Old-Babylonian clay tablet shown above, which is held in the British Museum in London, tells the story of Atrahasis, dated to 1635 BCE in the conventional chronology. When dealing with flood myths, one must tread with great care and not leap to conclusions. There is a good possibility that at least some variations commemorate local floods of the kind that sometimes occur when earthquakes or tsunamis strike. Nevertheless, the myths that speak of a universal inundation tend to relate to the cosmic axis in the centre of the world, a feature rarely if ever explored in the existing literature. This connection takes essentially two forms. A large class of myths portray the axis – in its familiar symbolic forms as a world mountain, acosmic tree, and so on – as the hero's place of refuge. An unambiguous example is the Greek Deucalion, whose ship safely lands on Mount Parnassus. It is no coincidence that Parnassus was also the celebrated 'navel of the earth'. According to another group of myths the waters of the flood poured forth when the axis was uprooted or displaced. This motif is particularly common in South-America. The Makiritare of Venezuela, for instance, recall the giant tree Marahuaka, that grew upside down with its roots in the sky. When it was cut down, the flood ensued. Such clues indicate that a large segment of flood myths may belong to the complex mythology of the axis mundi. As argued on these pages, the referent of these 'axis myths' was a stupendous high-energy plasma discharge tube with a semi-permanent character, whose existence was terminated amid catastrophic circumstances. If this model is right and the outburst of the flood had something to do with the disruption of this plasma column, one might contemplate the possibility that the water of the flood was not actually water, but a symbolic expression of glowing plasma. Far-fetched as this may sound at first, this assumption would actually clarify various issues. Commentators have often noted that, in many myths, the flood comes down from the sky. Unless we are to resurrect the antiquated idea of 'watery comets' discharging their wet burden, such assertions do not make much sense. Apart from that, a significant number of flood myths insist that the water was no ordinary water, but a different substance – hot and fiery. Jewish legend had it that the rain was hot, scalding the skin of the sinners. The Makah of Washington, the Quileute, the Chimakum, the Salinan of California and the Ipurina of Brazilian Amazonia agreed that the earth was overwhelmed by a hot flood coming down from the sky. This intriguing lead does not seem to have been followed by any specialists in the field, but the image of an outburst of 'fire-water' certainly reminds one of a return to chaos, in which water and fire were commingled into a single substance. The recurrent links of the flood with the world axis and an outflow of 'fire-water' spur a renewed examination of this fascinating body of folklore, Contributed by Rens van der Sluijs |

|

|

Copyright 2005: thunderbolts.info |

||

The Flood

In those very early times there was a man named Deucalion, and he was the son of Prometheus. He was only a common man and not a Titan like his great father, and yet he was known far and wide for his good deeds and the uprightness of his life. His wife’s name was Pyrrha, and she was one of the fairest of the daughters of men.

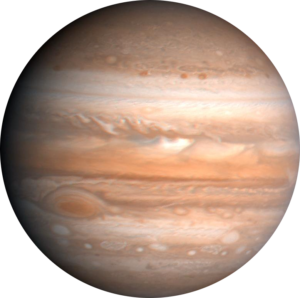

After Jupiter had bound Prometheus on Mount Caucasus and had sent diseases and cares into the world, men became very, very wicked. They no longer built houses and tended their flocks and lived together in peace; but every man was at war with his neighbor, and there was no law nor safety in all the land. Things were in much worse case now than they had been before Prometheus had come among men, and that was just what Jupiter wanted. But as the world became wickeder and wickeder every day, he began to grow weary of seeing so much bloodshed and of hearing the cries of the oppressed and the poor.

“These men,” he said to his mighty company, “are nothing but a source of trouble. When they were good and happy, we felt afraid lest they should become greater than ourselves; and now they are so terribly wicked that we are in worse danger than before. There is only one thing to be done with them, and that is to destroy them every one.”

So he sent a great rain-storm upon the earth, and it rained day and night for a long time; and the sea was filled to the brim, and the water ran over the land and covered first the plains and then the forests and then the hills. But men kept on fighting and robbing, even while the rain was pouring down and the sea was coming up over the land.

No one but Deucalion, the son of Prometheus, was ready for such a storm. He had never joined in any of the wrong doings of those around him, and had often told them that unless they left off their evil ways there would be a day of reckoning in the end. Once every year he had gone to the land of the Caucasus to talk with his father, who was hanging chained to the mountain peak.

“The day is coming,” said Prometheus, “when Jupiter will send a flood to destroy mankind from the earth. Be sure that you are ready for it, my son.”

And so when the rain began to fall, Deucalion drew from its shelter a boat which he had built for just such a time. He called fair Pyrrha, his wife, and the two sat in the boat and were floated safely on the rising waters. Day and night, day and night, I cannot tell how long, the boat drifted hither and thither. The tops of the trees were hidden by the flood, and then the hills and then the mountains; and Deucalion and Pyrrha could see nothing anywhere but water, water, water–and they knew that all the people in the land had been drowned.

After a while the rain stopped falling, and the clouds cleared away, and the blue sky and the golden sun came out overhead. Then the water began to sink very fast and to run off the land towards the sea; and early the very next day the boat was drifted high upon a mountain called Parnassus, and Deucalion and Pyrrha stepped out upon the dry land. After that, it was only a short time until the whole country was laid bare, and the trees shook their leafy branches in the wind, and the fields were carpeted with grass and flowers more beautiful than in the days before the flood.

But Deucalion and Pyrrha were very sad, for they knew that they were the only persons who were left alive in all the land. At last they started to walk down the mountain side towards the plain, wondering what would become of them now, all alone as they were in the wide world. While they were talking and trying to think what they should do, they heard a voice behind them. They turned and saw a noble young prince standing on one of the rocks above them. He was very tall, with blue eyes and yellow hair. There were wings on his shoes and on his cap, and in his hands he bore a staff with golden serpents twined around it. They knew at once that he was Mercury, the swift messenger of the Mighty Ones, and they waited to hear what he would say.

“Is there anything that you wish?” he asked. “Tell me, and you shall have whatever you desire.”

“We should like, above all things,” said Deucalion, “to see this land full of people once more; for without neighbors and friends, the world is a very lonely place indeed.”

“Go on down the mountain,” said Mercury, “and as you go, cast the bones of your mother over your shoulders behind you;” and, with these words, he leaped into the air and was seen no more.

“What did he mean?” asked Pyrrha.

“Surely I do not know,” said Deucalion. “But let us think a moment. Who is our mother, if it is not the Earth, from whom all living things have sprung? And yet what could he mean by the bones of our mother?”

“Perhaps he meant the stones of the earth,” said Pyrrha. “Let us go on down the mountain, and as we go, let us pick up the stones in our path and throw them over our shoulders behind us.”

“It is rather a silly thing to do,” said Deucalion; “and yet there can be no harm in it, and we shall see what will happen.”

And so they walked on, down the steep slope of Mount Parnassus, and as they walked they picked up the loose stones in their way and cast them over their shoulders; and strange to say, the stones which Deucalion threw sprang up as full-grown men, strong, and handsome, and brave; and the stones which Pyrrha threw sprang up as full-grown women, lovely and fair. When at last they reached the plain they found themselves at the head of a noble company of human beings, all eager to serve them.

So Deucalion became their king, and he set them in homes, and taught them how to till the ground, and how to do many useful things; and the land was filled with people who were happier and far better than those who had dwelt there before the flood. And they named the country Hellas, after Hellen, the son of Deucalion and Pyrrha; and the people are to this day called Hellenes.

But we call the country Greece.