Rough Notes:

Zeus

| Zeus | |

|---|---|

| God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, and justice | |

|

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak |

| Personal Information | |

| Consort | Hera and various others |

| Children | Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Parents | Cronus and Rhea |

| Siblings | Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Chiron |

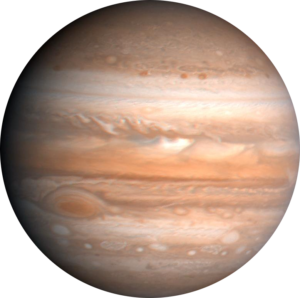

| Roman equivalent | Jupiter[2] |

| This article contains special characters.Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols. |

Zeus (/ˈzjuːs/;[3] Greek: Ζεύς Zeús [zdeǔ̯s])[4] is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, who ruled as king of the gods of Mount Olympus. His name is cognate with the first element of his Roman equivalent Jupiter. His mythologies and powers are similar, though not identical, to those of Indo-European deities such as Indra, Jupiter, Perun, Thor, and Odin.[5][6][7]

Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, the youngest of his siblings to be born, though sometimes reckoned the eldest as the others required disgorging from Cronus’s stomach. In most traditions, he is married to Hera, by whom he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe, and Hephaestus.[8] At the oracle of Dodona, his consort was said to be Dione, by whom the Iliad states that he fathered Aphrodite.[11] Zeus was also infamous for his erotic escapades. These resulted in many godly and heroic offspring, including Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses.[8]

He was respected as an allfather who was chief of the gods[12] and assigned the others to their roles:[13] “Even the gods who are not his natural children address him as Father, and all the gods rise in his presence.”[14][15] He was equated with many foreign weather gods, permitting Pausanias to observe “That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men”.[16] Zeus’ symbols are the thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak. In addition to his Indo-European inheritance, the classical “cloud-gatherer” (Greek: Νεφεληγερέτα, Nephelēgereta)[17] also derives certain iconographic traits from the cultures of the ancient Near East, such as the scepter. Zeus is frequently depicted by Greek artists in one of two poses: standing, striding forward with a thunderbolt leveled in his raised right hand, or seated in majesty.

Contents

[hide]

Name

The god’s name in the nominative is Ζεύς Zeús. It is inflected as follows: vocative: Ζεῦ Zeû; accusative: Δία Día; genitive: Διός Diós; dative: Διί Dií. Diogenes Laertius quotes Pherecydes of Syros as spelling the name, Ζάς.[18]

Zeus is the Greek continuation of *Di̯ēus, the name of the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also called *Dyeus ph2tēr (“Sky Father”).[19][20] The god is known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic Sanskrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European vocative *dyeu-ph2tēr),[21] deriving from the root *dyeu– (“to shine”, and in its many derivatives, “sky, heaven, god”).[19] Zeus is the only deity in the Olympic pantheon whose name has such a transparent Indo-European etymology.[22]

The earliest attested forms of the name are the Mycenaean Greek ??, di-we and ??, di-wo, written in the Linear B syllabic script.[23]

Plato, in his Cratylus, gives a folk etymology of Zeus meaning “cause of life always to all things,” because of puns between alternate titles of Zeus (Zen and Dia) with the Greek words for life and “because of.”[24] This etymology, along with Plato’s entire method of deriving etymologies, is not supported by modern scholarship.[25][26]

Mythology

Birth

Cronus sired several children by Rhea: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon, but swallowed them all as soon as they were born, since he had learned from Gaia and Uranus that he was destined to be overthrown by his son as he had previously overthrown Uranus, his own father, an oracle that Rhea heard and wished to avert.

When Zeus was about to be born, Rhea sought Gaia to devise a plan to save him, so that Cronus would get his retribution for his acts against Uranus and his own children. Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Crete, handing Cronus a rock wrapped in swaddling clothes, which he promptly swallowed.[27]

Infancy

Rhea hid Zeus in a cave on Mount Ida in Crete. According to varying versions of the story:

- He was then raised by Gaia.

- He was raised by a goat named Amalthea, while a company of Kouretes— soldiers, or smaller gods— danced, shouted and clashed their spears against their shields so that Cronus would not hear the baby’s cry (see cornucopia). According to some versions of this story he was reared by Amalthea in a cave called Dictaeon Andron(Psychro Cave) in Lasithi plateau.

- He was raised by a nymph named Adamanthea. Since Cronus ruled over the Earth, the heavens and the sea, she hid him by dangling him on a rope from a tree so he was suspended between earth, sea and sky and thus, invisible to his father.

- He was raised by a nymph named Cynosura. In gratitude, Zeus placed her among the stars.

- He was raised by Melissa, who nursed him with goat’s milk and honey.

- He was raised by a shepherd family under the promise that their sheep would be saved from wolves.

King of the gods

Colossal seated Marnasfrom Gaza portrayed in the style of Zeus. Roman period Marnas[28] was the chief divinity of Gaza (Istanbul Archaeology Museum).

After reaching manhood, Zeus forced Cronus to disgorge first the stone (which was set down at Pytho under the glens of Parnassus to be a sign to mortal men, the Omphalos) then his siblings in reverse order of swallowing. In some versions, Metis gave Cronus an emetic to force him to disgorge the babies, or Zeus cut Cronus’s stomach open. Then Zeus released the brothers of Cronus, the Hecatonchires and the Cyclopes, from their dungeon in Tartarus, killing their guard, Campe.

As a token of their appreciation, the Cyclopes gave him thunder and the thunderbolt, or lightning, which had previously been hidden by Gaia. Together, Zeus, his brothers and sisters, Hecatonchires and Cyclopes overthrew Cronus and the other Titans, in the combat called the Titanomachy. The defeated Titans were then cast into a shadowy underworld region known as Tartarus. Atlas, one of the titans who fought against Zeus, was punished by having to hold up the sky.

After the battle with the Titans, Zeus shared the world with his elder brothers, Poseidon and Hades, by drawing lots: Zeus got the sky and air, Poseidon the waters, and Hades the world of the dead (the underworld). The ancient Earth, Gaia, could not be claimed; she was left to all three, each according to their capabilities, which explains why Poseidon was the “earth-shaker” (the god of earthquakes) and Hades claimed the humans who died (see also Penthus).

Gaia resented the way Zeus had treated the Titans, because they were her children. Soon after taking the throne as king of the gods, Zeus had to fight some of Gaia’s other children, the monsters Typhon and Echidna. He vanquished Typhon and trapped him under Mount Etna, but left Echidna and her children alive.

Zeus and Hera

Zeus was brother and consort of Hera. By Hera, Zeus sired Ares, Hebe and Hephaestus, though some accounts say that Hera produced these offspring alone. Some also include Eileithyia, Eris, Enyo and Angelos as their daughters. In the section of the Iliad known to scholars as the Deception of Zeus, the two of them are described as having begun their sexual relationship without their parents knowing about it.[29] The conquests of Zeus among nymphs and the mythic mortal progenitors of Hellenic dynasties are famous. Olympian mythography even credits him with unions with Leto, Demeter, Metis, Themis, Eurynome and Mnemosyne.[30][31] Other relationships with immortals included Dione and Maia. Among mortals were Semele, Io, Europa and Leda (for more details, see below) and with the young Ganymede (although he was mortal Zeus granted him eternal youth and immortality).

Many myths render Hera as jealous of his amorous conquests and a consistent enemy of Zeus’s mistresses and their children by him. For a time, a nymph named Echo had the job of distracting Hera from his affairs by talking incessantly, and when Hera discovered the deception, she cursed Echo to repeat the words of others.

Consorts and children

1The Greeks variously claimed that the Moires/Fates were the daughters of Zeus and the Titaness Themis or of primordial beings like Chaos, Nyx, or Ananke.

2The Charites/Graces were usually considered the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome but they were also said to be daughters of Dionysus and Aphrodite or of Helios and the naiad Aegle.

3Some accounts say that Ares, Hebe, and Hephaestus were born parthenogenetically.

4According to one version, Athena is said to be born parthenogenetically.

5Helen was either the daughter of Leda or Nemesis.

6Tyche is usually considered a daughter of Aphrodite and Hermes.

Roles and epithets

Roman marble colossal head of Zeus, 2nd century AD (British Museum)[36]

Zeus played a dominant role, presiding over the Greek Olympian pantheon. He fathered many of the heroes and was featured in many of their local cults. Though the Homeric “cloud collector” was the god of the sky and thunder like his Near-Eastern counterparts, he was also the supreme cultural artifact; in some senses, he was the embodiment of Greek religious beliefs and the archetypal Greek deity.

Aside from local epithets that simply designated the deity as doing something random at some particular place, the epithets or titles applied to Zeus emphasized different aspects of his wide-ranging authority:

- Zeus Aegiduchos or Aegiochos: Usually taken as Zeus as the bearer of the Aegis, the divine shield with the head of Medusa across it,[37][38][39] although others derive it from “goat” (αἴξ) and okhē (οχή) in reference to Zeus’s nurse, the divine goat Amalthea.[40][41]

- Zeus Agoraeus: Zeus as patron of the marketplace (agora) and punisher of dishonest traders.

- Zeus Horkios: Zeus as keeper of oaths. Exposed liars were made to dedicate a votive statue to Zeus, often at the sanctuary at Olympia

- Zeus Olympios: Zeus as king of the gods and patron of the Panhellenic Games at Olympia

- Zeus Panhellenios (“Zeus of All the Greeks“): worshipped at Aeacus‘s temple on Aegina

- Zeus Xenios, Philoxenon, or Hospites: Zeus as the patron of hospitality (xenia) and guests, avenger of wrongs done to strangers

Additional names and epithets for Zeus are also:

- Abrettenus (Ἀβρεττηνός): surname of Zeus in Mysia[42]

- Apemius: Zeus as the averter of ills

- Apomyius Zeus as one who dispels flies

- Astrapios (“Lightninger”): Zeus as a weather god

- Bottiaeus: Worshipped at Antioch[43]

- Brontios (“Thunderer”): Zeus as a weather god

- Diktaios: Zeus as lord of the Dikte mountain range, worshipped from Mycenaean times on Crete[44]

- Ithomatas: Worshipped at Mount Ithome in Messenia

- Zeus Adados: A Hellenization of the Canaanite Hadad and Assyrian Adad, particularly his solar cult at Heliopolis[45]

- Zeus Bouleus: Worshipped at Dodona, the earliest oracle, along with Zeus Naos

- Zeus Georgos (Ζεὺς Γεωργός, “Zeus the Farmer”): Zeus as god of crops and the harvest, worshipped in Athens

- Zeus Helioupolites (“Heliopolite” or “Heliopolitan Zeus”): A Hellenization of the Canaanite Baʿal (probably Hadad) worshipped as a sun god at Heliopolis (modern Baalbek)[45]

- Zeus Kasios (“Zeus of Mount Kasios” the modern Jebel Aqra): Worshipped at a site on the Syrian–Turkish border, a Hellenization of the Canaanite mountain and weather god Baal Zephon

- Zeus Labrandos (“Zeus of Labraunda“): Worshiped at Caria, depicted with a double-edged axe (labrys), a Hellenization of the Hurrian weather god Teshub

- Zeus Meilichios (“Zeus the Easily-Entreated”): Worshipped at Athens, a form of the archaic chthonic daimon Meilichios

- Zeus Naos: Worshipped at Dodona, the earliest oracle, along with Zeus Bouleus

- Zeus Tallaios (“Solar Zeus”): Worshipped on Crete

Cults of Zeus

Marble eagle from the sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos, Archaeological Museum of Dion.

Panhellenic cults

The major center where all Greeks converged to pay honor to their chief god was Olympia. Their quadrennial festival featured the famous Games. There was also an altar to Zeus made not of stone, but of ash, from the accumulated remains of many centuries’ worth of animals sacrificed there.

Outside of the major inter-polis sanctuaries, there were no modes of worshipping Zeus precisely shared across the Greek world. Most of the titles listed below, for instance, could be found at any number of Greek temples from Asia Minor to Sicily. Certain modes of ritual were held in common as well: sacrificing a white animal over a raised altar, for instance.

Zeus Velchanos

With one exception, Greeks were unanimous in recognizing the birthplace of Zeus as Crete. Minoan culture contributed many essentials of ancient Greek religion: “by a hundred channels the old civilization emptied itself into the new”, Will Durant observed,[46] and Cretan Zeus retained his youthful Minoan features. The local child of the Great Mother, “a small and inferior deity who took the roles of son and consort”,[47] whose Minoan name the Greeks Hellenized as Velchanos, was in time assumed as an epithet by Zeus, as transpired at many other sites, and he came to be venerated in Crete as Zeus Velchanos (“boy-Zeus”), often simply the Kouros.

In Crete, Zeus was worshipped at a number of caves at Knossos, Ida and Palaikastro. In the Hellenistic period a small sanctuary dedicated to Zeus Velchanos was founded at the Hagia Triada site of a long-ruined Minoan palace. Broadly contemporary coins from Phaistos show the form under which he was worshiped: a youth sits among the branches of a tree, with a cockerel on his knees.[48] On other Cretan coins Velchanos is represented as an eagle and in association with a goddess celebrating a mystic marriage.[49] Inscriptions at Gortyn and Lyttos record a Velchania festival, showing that Velchanios was still widely venerated in Hellenistic Crete.[50]

The stories of Minos and Epimenides suggest that these caves were once used for incubatory divination by kings and priests. The dramatic setting of Plato‘s Laws is along the pilgrimage-route to one such site, emphasizing archaic Cretan knowledge. On Crete, Zeus was represented in art as a long-haired youth rather than a mature adult and hymned as ho megas kouros, “the great youth”. Ivory statuettes of the “Divine Boy” were unearthed near the Labyrinth at Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans.[51] With the Kouretes, a band of ecstatic armed dancers, he presided over the rigorous military-athletic training and secret rites of the Cretan paideia.

The myth of the death of Cretan Zeus, localised in numerous mountain sites though only mentioned in a comparatively late source, Callimachus,[52] together with the assertion of Antoninus Liberalis that a fire shone forth annually from the birth-cave the infant shared with a mythic swarm of bees, suggests that Velchanos had been an annual vegetative spirit.[53] The Hellenistic writer Euhemerus apparently proposed a theory that Zeus had actually been a great king of Crete and that posthumously, his glory had slowly turned him into a deity. The works of Euhemerus himself have not survived, but Christian patristic writers took up the suggestion.

Zeus Lykaios

Laurel-wreathed head of Zeus on a gold stater, Lampsacus, c 360–340 BC (Cabinet des Médailles).

The epithet Zeus Lykaios (“wolf-Zeus”) is assumed by Zeus only in connection with the archaic festival of the Lykaia on the slopes of Mount Lykaion (“Wolf Mountain”), the tallest peak in rustic Arcadia; Zeus had only a formal connection[54] with the rituals and myths of this primitive rite of passage with an ancient threat of cannibalism and the possibility of a werewolf transformation for the ephebes who were the participants.[55] Near the ancient ash-heap where the sacrifices took place[56] was a forbidden precinct in which, allegedly, no shadows were ever cast.[57]

According to Plato,[58] a particular clan would gather on the mountain to make a sacrifice every nine years to Zeus Lykaios, and a single morsel of human entrails would be intermingled with the animal’s. Whoever ate the human flesh was said to turn into a wolf, and could only regain human form if he did not eat again of human flesh until the next nine-year cycle had ended. There were games associated with the Lykaia, removed in the fourth century to the first urbanization of Arcadia, Megalopolis; there the major temple was dedicated to Zeus Lykaios.

There is, however, the crucial detail that Lykaios or Lykeios (epithets of Zeus and Apollo) may derive from Proto-Greek *λύκη, “light”, a noun still attested in compounds such as ἀμφιλύκη, “twilight”, λυκάβας, “year” (lit. “light’s course”) etc. This, Cook argues, brings indeed much new ‘light’ to the matter as Achaeus, the contemporary tragedian of Sophocles, spoke of Zeus Lykaios as “starry-eyed”, and this Zeus Lykaios may just be the Arcadian Zeus, son of Aether, described by Cicero. Again under this new signification may be seen Pausanias‘ descriptions of Lykosoura being ‘the first city that ever the sun beheld’, and of the altar of Zeus, at the summit of Mount Lykaion, before which stood two columns bearing gilded eagles and ‘facing the sun-rise’. Further Cook sees only the tale of Zeus’ sacred precinct at Mount Lykaion allowing no shadows referring to Zeus as ‘god of light’ (Lykaios).[59]

Additional cults of Zeus

|

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Although etymology indicates that Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored a local Zeus who lived underground. Athenians and Sicilians honored Zeus Meilichios (“kindly” or “honeyed”) while other cities had Zeus Chthonios (“earthy”), Zeus Katachthonios (“under-the-earth”) and Zeus Plousios (“wealth-bringing”). These deities might be represented as snakes or in human form in visual art, or, for emphasis as both together in one image. They also received offerings of black animal victims sacrificed into sunken pits, as did chthonic deities like Persephone and Demeter, and also the heroes at their tombs. Olympian gods, by contrast, usually received white victims sacrificed upon raised altars.

In some cases, cities were not entirely sure whether the daimon to whom they sacrificed was a hero or an underground Zeus. Thus the shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia might belong to the hero Trophonius or to Zeus Trephonius (“the nurturing”), depending on whether you believe Pausanias, or Strabo. The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus outside of Thebes, and the Spartans even had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon.

Non-panhellenic cults

In addition to the Panhellenic titles and conceptions listed above, local cults maintained their own idiosyncratic ideas about the king of gods and men. With the epithet Zeus Aetnaeus he was worshiped on Mount Aetna, where there was a statue of him, and a local festival called the Aetnaea in his honor.[60] Other examples are listed below. As Zeus Aeneius or Zeus Aenesius, he was worshiped in the island of Cephalonia, where he had a temple on Mount Aenos.[61]

Oracles of Zeus

Roman cast terracotta of ram-horned Jupiter Ammon, 1st century AD (Museo Barracco, Rome).

Although most oracle sites were usually dedicated to Apollo, the heroes, or various goddesses like Themis, a few oracular sites were dedicated to Zeus. In addition, some foreign oracles, such as Baʿal‘s at Heliopolis, were associated with Zeus in Greek or Jupiter in Latin.

The Oracle at Dodona

The cult of Zeus at Dodona in Epirus, where there is evidence of religious activity from the second millennium BC onward, centered on a sacred oak. When the Odyssey was composed (circa 750 BC), divination was done there by barefoot priests called Selloi, who lay on the ground and observed the rustling of the leaves and branches.[62] By the time Herodotus wrote about Dodona, female priestesses called peleiades (“doves”) had replaced the male priests.

Zeus’s consort at Dodona was not Hera, but the goddess Dione — whose name is a feminine form of “Zeus”. Her status as a titaness suggests to some that she may have been a more powerful pre-Hellenic deity, and perhaps the original occupant of the oracle.

The Oracle at Siwa

The oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt did not lie within the bounds of the Greek world before Alexander‘s day, but it already loomed large in the Greek mind during the archaic era: Herodotus mentions consultations with Zeus Ammon in his account of the Persian War. Zeus Ammon was especially favored at Sparta, where a temple to him existed by the time of the Peloponnesian War.[63]

After Alexander made a trek into the desert to consult the oracle at Siwa, the figure arose in the Hellenistic imagination of a Libyan Sibyl.

Zeus and foreign gods

Evolution of Zeus Nikephoros (“Zeus holding Nike“) on Indo-Greekcoinage: from the Classical motif of Nike handing the wreath of victory to Zeus himself (left, coin of Heliocles I 145-130 BC), then to a baby elephant (middle, coin of Antialcidas 115-95 BC), and then to the Wheel of the Law, symbol of Buddhism (right, coin of Menander II 90–85 BC).

Zeus as Vajrapāni, the protector of the Buddha. 2nd century, Greco-Buddhist art.[64]

Zeus was identified with the Roman god Jupiter and associated in the syncretic classical imagination (see interpretatio graeca) with various other deities, such as the Egyptian Ammon and the Etruscan Tinia. He, along with Dionysus, absorbed the role of the chief Phrygian god Sabazios in the syncretic deity known in Rome as Sabazius. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes erected a statue of Zeus Olympios in the Judean Temple in Jerusalem.[65] Hellenizing Jews referred to this statue as Baal Shamen (in English, Lord of Heaven).[66]

Zeus and the sun

Zeus is occasionally conflated with the Hellenic sun god, Helios, who is sometimes either directly referred to as Zeus’ eye,[67] or clearly implied as such. Hesiod, for instance, describes Zeus’s eye as effectively the sun.[68] This perception is possibly derived from earlier Proto-Indo-European religion, in which the sun is occasionally envisioned as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr (see Hvare-khshaeta).[69]

The Cretan Zeus Tallaios had solar elements to his cult. “Talos” was the local equivalent of Helios.[70]

Zeus in philosophy

In Neoplatonism, Zeus’s relation to the gods familiar from mythology is taught as the Demiurge or Divine Mind. Specifically within Plotinus‘s work the Enneads[71] and the Platonic Theology of Proclus.

Zeus in the Bible

Zeus is mentioned in the New Testament twice, first in Acts 14:8–13: When the people living in Lystra saw the Apostle Paul heal a lame man, they considered Paul and his partner Barnabas to be gods, identifying Paul with Hermes and Barnabas with Zeus, even trying to offer them sacrifices with the crowd. Two ancient inscriptions discovered in 1909 near Lystra testify to the worship of these two gods in that city.[72] One of the inscriptions refers to the “priests of Zeus”, and the other mentions “Hermes Most Great”” and “Zeus the sun-god”.[73]

The second occurrence is in Acts 28:11: the name of the ship in which the prisoner Paul set sail from the island of Malta bore the figurehead “Sons of Zeus” aka Castor and Pollux.

The deuterocanonical book of 2 Maccabees 6:1, 2 talks of King Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), who in his attempt to stamp out the Jewish religion, directed that the temple at Jerusalem be profaned and rededicated to Zeus (Jupiter Olympius).[74]

Zeus in the Iliad

Jupiter and Juno on Mount Ida by James Barry, 1773 (City Art Galleries, Sheffield.)

The Iliad is a poem by Homer about the Trojan war and the battle over the City of Troy. As God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice, Zeus controlled ancient Greece and all of the mortals and immortals living there.[75] The Iliad covers the Trojan War, in which Zeus plays a major part.

Notable Scenes that include Zeus[76][77]

- Book 2: Zeus sends Agamemnon a dream and is able to partially control his decisions because of the effects of the dream

- Book 4: Zeus promises Hera to ultimately destroy the City of Troy at the end of the war

- Book 7: Zeus and Poseidon ruin the Achaeans fortress

- Book 8: Zeus prohibits the other Gods from fighting each other and has to return to Mount Ida where he can think over his decision that the Greeks will lose the war

- Book 14: Zeus is seduced by Hera and becomes distracted while she helps out the Greeks

- Book 15: Zeus wakes up and realizes that Poseidon his own brother has been helping out the Greeks, while also sending Hector and Apollo to help fight the Trojans ensuring that the City of Troy will fall

- Book 16: Zeus is upset that he couldn’t help save Sarpedon’s life because it would then contradict his previous decisions

- Book 17: Zeus is emotionally hurt by the fate of Hector

- Book 20: Zeus lets the other Gods help out their respective sides in the war

- Book 24: Zeus demands that Achilles (his son) release the corpse of Hector to be buried honourably

Zeus’s notable conflicts

The most notable conflict in Zeus’s history was his struggle for power. Zeus’s parents Cronus and Rhea ruled the Ancient World after taking control from Uranus, Cronus’s father. When Cronus realized that he wanted power for the rest of time he started to eat his children, Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. When Rhea realized what was going on, she quickly saved their youngest child, Zeus. Having escaped, Zeus was spared because of the swiftness of Rhea tricking Cronus into thinking she consumed Zeus. She wrapped a stone in a blanket, and Cronus swallowed it thinking he was swallowing his last child.[78] As a result of this, Zeus was shipped off to live on the island of Crete.

When Zeus was atop Mount Olympus he grew upset with mankind and the sacrifices they were performing on one another. Furiously, he decided it would be smart to wipe out mankind with a gigantic flood using the help of his brother Poseidon, King of the Seas. Killing every human except Deucalion and Pyrrha, Zeus flooded the entire planet but then realized he then had to restore society with new people. After clearing all the water, he had Deucalion and Pyrrah create humans to repopulate the earth using stones that became humans. These stones represented the “hardness” of mankind and the man life. This story has been told different ways and in different time periods between Ancient Greek Mythology and The Bible, although the base of the story remains true.[79]

Throughout history Zeus has used violence to get his way, or even terrorize humans. As God of the sky he has the power to hurl lightning bolts as his weapon of choice. Since lightning is quite powerful and sometimes deadly, it is a bold sign when lightning strikes because it is known that Zeus most likely threw the bolt.[80]

In modern culture

Depictions of Zeus as a bull, the form he took when abducting Europa, are found on the Greek 2-euro coin and on the United Kingdom identity card for visa holders. Mary Beard, professor of Classics at Cambridge University, has criticised this for its apparent celebration of rape.[81]

Genealogy of the Olympians

| [hide]Olympians’ family tree [82] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Argive genealogy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Achaean League

- Agetor

- Deception of Zeus

- Hetairideia – Thessalian Festival to Zeus

- Temple of Zeus, Olympia

- Zanes of Olympia – Statues of Zeus

Notes

- Jump up^ The sculpture was presented to Louis XIV as Aesculapius but restored as Zeus, ca. 1686, by Pierre Granier, who added the upraised right arm brandishing the thunderbolt. Marble, middle 2nd century CE. Formerly in the ‘Allée Royale’, (Tapis Vert) in the Gardens of Versailles, now conserved in the Louvre Museum (Official on-line catalog)

- Jump up^ Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia, The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215.

- Jump up^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. “Zeus, n.” Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1921.

- Jump up^ In classical Attic Greek.

- Jump up^ Thomas Berry (1996). Religions of India: Hinduism, Yoga, Buddhism. Columbia University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-231-10781-5.

- Jump up^ T. N. Madan (2003). The Hinduism Omnibus. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-566411-9.

- Jump up^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2015). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hamilton, Edith (1942). Mythology (1998 ed.). New York: Back Bay Books. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-316-34114-1.

- Jump up^ Homer, Il., Book V.

- Jump up^ Plato, Symp., 180e.

- Jump up^ There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite’s origins: Hesiod‘s Theogony claims that she was born from the foam of the sea after Cronos castrated Uranus, making her Uranus’s daughter but Homer‘s Iliad has Aphrodite as the daughter of Zeus and Dione.[9] A speaker in Plato‘s Symposium offers that they were separate figures: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.[10]

- Jump up^ Homeric Hymns.

- Jump up^ Hesiod, Theogony.

- Jump up^ Burkert, Greek Religion.

- Jump up^ See, e.g., Homer, Il., I.503 & 533.

- Jump up^ Pausanias, 2.24.2.

- Jump up^ Νεφεληγερέτα. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Jump up^ Laertius, Diogenes (1972) [1925]. “1.11”. In Hicks, R.D. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. “1.11”. Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers (in Greek).

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Zeus”. American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- Jump up^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 499.

- Jump up^ Harper, Douglas. “Jupiter”. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Jump up^ Burkert (1985). Greek Religion. p. 321. ISBN 0-674-36280-2.

- Jump up^ “The Linear B word di-we”. “The Linear B word di-wo”. Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of Ancient languages.

- Jump up^ “Plato’s Cratylus,” by Plato, ed. by David Sedley, Cambridge University Press, 6 Nov 2003, p.91

- Jump up^ “The Makers of Hellas”.

- Jump up^ “Limiting the Arbitrary”.

- Jump up^ “Greek and Roman Mythology.”. Mythology: Myths, Legends, & Fantasy. Sweet Water Press. 2003. p. 21. ISBN 9781468265903.

- Jump up^

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Gaza“. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.; Johannes Hahn: Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt; The Holy Land and the Bible

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “Gaza“. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.; Johannes Hahn: Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt; The Holy Land and the Bible - Jump up^ Iliad, Book 14, line 294

- Jump up^ Theogony 886–900.

- Jump up^ Theogony 901–911.

- Jump up^ Hyginus, Fabulae 155

- Jump up^ Scholia on Pindar, Olympian Ode 9, 107

- Jump up^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s. v. Dōdōne, with a reference to Acestodorus

- Jump up^ Photios (1824). “190.489R”. In Bekker, August Immanuel. Myriobiblon (in Greek). Tomus alter. Berlin: Ge. Reimer. p. 152a. At the Internet Archive.

“190.152a” (PDF). Myriobiblon (in Greek). Interreg Δρόμοι της πίστης – Ψηφιακή Πατρολογία. 2006. p. 163. At khazarzar.skeptik.net. - Jump up^ The bust below the base of the neck is eighteenth century. The head, which is roughly worked at back and must have occupied a niche, was found at Hadrian’s Villa, Tivoli and donated to the British Museum by John Thomas Barber Beaumont in 1836. BM 1516. (British Museum, A Catalogue of Sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1904).

- Jump up^ Homer, Iliad i. 202, ii. 157, 375, &c.

- Jump up^ Pindar, Isthmian Odes iv. 99

- Jump up^ Hyginus, Poetical Astronomy ii. 13

- Jump up^ Spanh. ad Callim. hymn. in Jov, 49

- Jump up^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). “Aegiduchos”. In Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. I. Boston. p. 26.

- Jump up^ Strab. xii. p. 574

- Jump up^ Libanius (2000). Antioch as a Centre of Hellenic Culture as Observed by Libanius. Translated with an introduction by A.F. Norman. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-85323-595-3.

- Jump up^ Δικταῖος in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cook, Arthur Bernard (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, I: Zeus God of the Bright Sky, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 549 ff..

- Jump up^ Durant, The Life of Greece (The Story of Civilization Part II, New York: Simon & Schuster) 1939:23.

- Jump up^ Rodney Castleden, Minoans: Life in Bronze-Age Crete, “The Minoan belief-system” (Routledge) 1990:125

- Jump up^ Pointed out by Bernard Clive Dietrich, The Origins of Greek Religion(de Gruyter) 1973:15.

- Jump up^ A.B. Cook, Zeus Cambridge University Press, 1914, I, figs 397, 398.

- Jump up^ Dietrich 1973, noting Martin P. Nilsson, Minoan-Mycenaean Religion, and Its Survival in Greek Religion 1950:551 and notes.

- Jump up^ “Professor Stylianos Alexiou reminds us that there were other divine boys who survived from the religion of the pre-Hellenic period — Linos, Ploutos and Dionysos — so not all the young male deities we see depicted in Minoan works of art are necessarily Velchanos” (Castleden 1990:125

- Jump up^ Richard Wyatt Hutchinson, Prehistoric Crete, (Harmondsworth: Penguin) 1968:204, mentions that there is no classical reference to the death of Zeus (noted by Dietrich 1973:16 note 78).

- Jump up^ “This annually reborn god of vegetation also experienced the other parts of the vegetation cycle: holy marriage and annual death when he was thought to disappear from the earth” (Dietrich 1973:15).

- Jump up^ In the founding myth of Lycaon‘s banquet for the gods that included the flesh of a human sacrifice, perhaps one of his sons, Nyctimus or Arcas. Zeus overturned the table and struck the house of Lyceus with a thunderbolt; his patronage at the Lykaia can have been little more than a formula.

- Jump up^ A morphological connection to lyke “brightness” may be merely fortuitous.

- Jump up^ Modern archaeologists have found no trace of human remains among the sacrificial detritus, Walter Burkert, “Lykaia and Lykaion”, Homo Necans, tr. by Peter Bing (University of California) 1983, p. 90.

- Jump up^ Pausanias 8.38.

- Jump up^ Republic 565d-e

- Jump up^ A. B. Cook (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. I, p.63, Cambridge University Press

- Jump up^ Schol. ad Pind. Ol. vi. 162

- Jump up^ Hesiod, according to a scholium on Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautika, ii. 297

- Jump up^ Odyssey 14.326-7

- Jump up^ Pausanias 3.18.

- Jump up^ “In the art of Gandhara Zeus became the inseparable companion of the Buddha as Vajrapani.” in Freedom, Progress, and Society, K. Satchidananda Murty, R. Balasubramanian, Sibajiban Bhattacharyya, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, 1986, p. 97

- Jump up^ 2 Maccabees 6:2

- Jump up^ David Syme Russel. Daniel. (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1981) 191.

- Jump up^ Sick, David H. (2004), “Mit(h)ra(s) and the Myths of the Sun”, Numen, 51 (4): 432–467, JSTOR 3270454

- Jump up^ Ljuba Merlina Bortolani, Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt: A Study of Greek and Egyptian Traditions of Divinity, Cambridge University Press, 13/10/2016

- Jump up^ West, Martin Litchfield (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth(PDF). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Jump up^ Karl Kerenyi, The Gods of the Greeks 1951:110.

- Jump up^ In Fourth Tractate ‘Problems of the Soul’ The Demiurge is identified as Zeus.10. “When under the name of Zeus we are considering the Demiurge we must leave out all notions of stage and progress, and recognize one unchanging and timeless life.”

- Jump up^ The translation of Hermes

- Jump up^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, edited by J. Orr, 1960, Vol. III, p. 1944.

- Jump up^ “The Second Book of the Maccabees”.

- Jump up^ “Zeus • Facts and Information on Greek God of the Sky Zeus”. Greek Gods & Goddesses. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- Jump up^ “The Gods in the Iliad”. department.monm.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Jump up^ Homer (1990). The Iliad. South Africa: Penguin Classics.

- Jump up^ “Zeus”. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- Jump up^ “Greek Gods”. AllAboutHistory.org. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Jump up^ “Zeus • Facts and Information on Greek God of the Sky Zeus”. Greek Gods & Goddesses. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Jump up^ A Point of View: The euro’s strange stories, BBC, retrieved 20/11/2011

- Jump up^ This chart is based upon Hesiod‘s Theogony, unless otherwise noted.

- Jump up^ According to Homer, Iliad 1.570–579, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312, Hephaestus was apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- Jump up^ According to Hesiod, Theogony 927–929, Hephaestus was produced by Hera alone, with no father, see Gantz, p. 74.

- Jump up^ According to Hesiod, Theogony 886–890, of Zeus’ children by his seven wives, Athena was the first to be conceived, but the last to be born; Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena “from his head”, see Gantz, pp. 51–52, 83–84.

- Jump up^ According to Hesiod, Theogony 183–200, Aphrodite was born from Uranus’ severed genitals, see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- Jump up^ According to Homer, Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus (Iliad3.374, 20.105; Odyssey 8.308, 320) and Dione (Iliad 5.370–71), see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

References

- Burkert, Walter, (1977) 1985. Greek Religion, especially section III.ii.1 (Harvard University Press)

- Cook, Arthur Bernard, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, (3 volume set), (1914–1925). New York, Bibilo & Tannen: 1964.

- Volume 1: Zeus, God of the Bright Sky, Biblo-Moser, June 1, 1964, ISBN 0-8196-0148-9 (reprint)

- Volume 2: Zeus, God of the Dark Sky (Thunder and Lightning), Biblo-Moser, June 1, 1964, ISBN 0-8196-0156-X

- Volume 3: Zeus, God of the Dark Sky (earthquakes, clouds, wind, dew, rain, meteorites)

- Druon, Maurice, The Memoirs of Zeus, 1964, Charles Scribner’s and Sons. (tr. Humphrey Hare)

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, Cults of the Greek States 5 vols. Oxford; Clarendon 1896–1909. Still the standard reference.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Graves, Robert; The Greek Myths, Penguin Books Ltd. (1960 edition)

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Mitford, William, The History of Greece, 1784. Cf. v.1, Chapter II, Religion of the Early Greeks

- Moore, Clifford H., The Religious Thought of the Greeks, 1916.

- Nilsson, Martin P., Greek Popular Religion, 1940.

- Nilsson, Martin P., History of Greek Religion, 1949.

- Rohde, Erwin, Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Greeks, 1925.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, Ancientlibrary.com, William Smith, Dictionary: “Zeus” Ancientlibrary.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zeus. |

- Greek Mythology Link, Zeus stories of Zeus in myth

- Theoi Project, Zeus summary, stories, classical art

- Theoi Project, Cult Of Zeus cult and statues

- Photo: Pagans Honor Zeus at Ancient Athens Temple from National Geographic