Rough Notes:

|

||||||

|

||||||

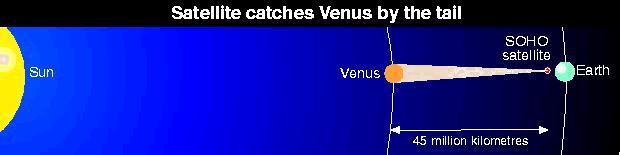

The ion tail of Venus. Credit: Jeff Hecht, New Scientist Magazine May 31, 1997.

Feb 20, 2008

Venus' Tail of the UnexpectedAncient peoples report that the planet Venus once had visible "ropes" stretching out to the Earth. Could a plasma glow discharge have been the cause?

The "induced magnetotail" that points away from Venus in the direction of the earth is a teardrop-shaped plasma structure filled with “a lot of little stringy things” that was first detected by NASA’s Pioneer Venus Orbiter in the late 1970s. In 1997, Europe’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) Satellite showed that the tail stretched some 45,000,000 kilometres into space, more than 600 times as far as anyone had realized and almost far enough to “tickle” the earth when the two planets are in line with the sun.

“In this sense”, scientists write, “Venus can be likened to a comet, which has an induced magnetotail of similar origin.”

Intriguingly, as has been abundantly documented on this forum, human societies outside the mainstream of western science have long associated the morning or evening star with just such a conspicuous “rope” or “string”. Particularly explicit are some examples drawn from the near-contemporary cosmology of native Australian communities.

The Ringu-Ringu people of central Queensland, “call the star Venus mimungoona or big eye” and assert that “no water exists in the star, but there are ropes which hang from its surface to the earth, by means of which the dwellers visit our planet from time to time, and assuage their thirst.”

And Manoowa Wongupali, a spokesman of the Jumbapoingo people of Milingimbi, to the northeast of Darwin, gave an explanation of the rising of the morning star in which a string of feathers features prominently: “When the two spirits Naikala and Birrowarr want to speak with spirits in other countries, they throw the pul pul, the tuft of white feathers, which is the morning star, into the sky and, when it is daylight, they pull the morning star, on the end of its string, down again to Buralku, the island of the spirits of the dead. The morning star on the end of its string lies coiled up in the dilly bag of one old man spirit. This dilly bag, called Battee, is the mother of the morning star. It is the womb. The tuft of white feathers, the morning star, is the child looking out of the dilly bag. And the string, coiled in the dilly bag, is the cord by which the child is joined to its mother.”

It goes without saying that “traditional” societies can only have learned about Venus’ plasma tail if the latter has at one time been visible to the unaided human eye. Certainly, the modern scientific understanding of the tail allows for the possibility that it plasma discharged, attaining a visible glow mode, at a time when the sun produced an extremely enhanced outflow of ions.

Contributed by Rens Van der Sluijs

Further reading:

The Mythology of the World Axis; Exploring the Role of Plasma in World Mythology

www.lulu.com/content/1085275The World Axis as an Atmospheric Phenomenon

www.lulu.com/content/1305081