Rough Notes:

Goddess

THE GREAT GODDESS

In prehistoric and early historic periods of human development, religions existed in which people revered their supreme creator as female.

The Great Goddess, the Divine Ancestress, was worshiped as far back as the Upper Paleolithic about 25,000 BC -- not 7000 BC as had been previously believed by archaeologists and scholars based on archaeological evidence. The last Goddess temples were closed about 500 AD.

Little has been written about the female deities who were worshiped in the most ancient periods of human existence and still today, the material there is has been almost totally ignored.

Most of the information and artifacts concerning the vast female religion, which flourished for thousands of years before the advent of the classical age of Greece, Judaism, Christianity, was dug out of the ground after the Second World War. It is these more recent excavations which have changed our view of our most ancient history.

GODDESS WORSHIP

Archaeological evidence proves that the Goddess religion existed and flourished in the Near and Middle East for thousands of years before the arrival of the patriarchal Abraham, first prophet of the male deity Yahweh.

Who was this Goddess? Why had a female, rather than a male, been designated as the supreme deity? How influential and significant was Her worship, and when had it actually begun?

Though goddesses have been worshiped in all areas of the world, we will focus on the religion as it evolved in the Near and Middle East, the cradle of western civilization. The development of the religion of the female deity in this area is intertwined with the earliest beginnings of religion so far discovered anywhere on earth.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

The archaeological evidence for the existence of this ancient religion comes in the form of statues, murals, inscriptions, clay tablets and papyri that recorded events. Legends and prayers revealed the form and attitudes of the religion and the nature of the deity. Many ancient legends often refer to ritual dramas. These were enacted at religious ceremonies of sacred festivals, coinciding with other ritual activities.

Comments were often found in the literature of one country about the religion or divinities of another. Most cultures have myths that explain their origins. However, these are not always the oldest.

There are numerous accounts of the antagonistic attitudes of Judaism, Christianity and Islam toward the sacred artifacts of the religions that preceded them, especially in the case of the Goddess worshiped in Canaan (Palestine).

THE GODDESS IN EVERY FORM

Accounts of Sun Goddesses were found in the lands of Canaan, Anatolia, Arabia and Australia, among the Eskimos, the Japanese and the Khasis of India.

Most astonishing of all was the discovery of numerous accounts of the female Creator of all existence, divinities who were credited with bringing forth not only the first people but the entire earth and the heavens above. There were records of such Goddesses in Sumer, Babylon, Egypt, Africa, Australia and China.

In India the Goddess Sarasvati was honored as the inventor of the original alphabet, while in Celtic Ireland the Goddess Brigit was esteemed as the patron deity of language. Texts revealed that it was the Goddess Nidaba in Sumer who was paid honor as the one who initially invented clay tablets and the art of writing.

Most significant was the archaeological evidence of the earliest examples of written language so far discovered; these were also located in Sumer, at the temple of the Queen of Heaven in Erech, written there over five thousand years ago.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE

In agreement with the generally accepted theory that women were responsible for the development of agriculture, as an extension of their food-gathering activities, there were female deities everywhere who were credited with this gift to civilization.

In Mesopotamia, where some of the earliest evidences of agricultural development have been found, the Goddess Ninlil was revered for having provided Her people with an understanding of planting and harvesting methods.

In nearly all areas of the world, female deities were extolled as healers, dispensers of curative herbs, roots, plants and other medical aids, casting the priestesses who attended the shrines into the role of physicians of those who worshiped there.

The Divine Ancestress was known as Astarte -- the Great Goddess, the Queen of Heaven, Innin, Inanna, Nan, Nut, Anat, Anahita, Istar Isis, Au Set, Ishara, Asherah, Ashtart, Attoret, Attar and Hathor. Each names denotes in the various languages and dialects of those who revered Her, different aspects of the Great Goddess.

THE ROOTS OF CIVILIZATION

Why do so many people educated in this century think of classical Greece as the first major culture when written language was in use and great cities built at least twenty-five centuries before that time?

And perhaps most important, why is it continually inferred that the age of the "pagan" religions, the time of the worship of female deities, was dark and chaotic, mysterious and evil, without the light of order and reason that supposedly accompanied the later male religions.

It has been archaeologically confirmed that the earliest law, government, medicine, agriculture, architecture, metallurgy, wheeled vehicles, ceramics, textiles and written language were initially developed in societies that worshipped the Goddess.

We may find ourselves wondering about the reasons for the lack of available information on societies who, for thousands of years, worshiped the ancient Creatress of the Universe.

NO WRITTEN RECORDS

The Upper Paleolithic period, though most of its sites have been found in Europe, is the conjectural foundation of the religion of the Goddess as it emerged in the later Neolithic Age of the Near East.

Since it precedes the time of written records and does not directly lead into an historical period that might have helped to explain it, the information on the Paleolithic existence of Goddess worship must at this time remain speculative. Theories on the origins of the Goddess in this period are founded on the juxtaposition of motherkinship customs to ancestor worship. They are based upon three separate lines of evidence.

The first relies on anthropological analogy to explain the initial development of matrilineal (mother-kinship) societies. Studies of "primitive" tribes over the last few centuries have led to the realization that some isolated "primitive" peoples, even in our own century, did not yet possess the conscious understanding of the relationship of sex to conception. The analogy is then drawn that Paleolithic people may have been at a similar level of biological awareness.

A MATRILINEAR LINE OF DESCENT

Accounts of descent in the family would be kept through the female line, going from mother to daughter rather than from father to son, as is the custom practiced today. Such a social structure is generally referred to as matrilineal, that is, based upon motherkinship. In such cultures not only the names, but titles, possessions and territorial rights are passed along through the female line, so that they may be retained within the family clan.

The second line of evidence concerns the beginnings of religious beliefs and rituals and their connection with matrilineal descent. There have been numerous studies of Paleolithic cultures, explorations of sites occupied by these people and the apparent rites connected with the disposal of their dead. These suggest that, as the earliest concepts of religion developed, they probably took the form of ancestor worship. An analogy can be drawn between the Paleolithic people and the religious concepts and rituals observed among many of the aboriginal tribes studied by anthropologists over the last two centuries.

THE UPPER PALEOLITHIC VENUS FIGURES

The third line of evidence, and the most tangible, derives from the numerous sculptures of women found in the Gravettian-Aurignacian cultures of the Upper Paleolithic Age. Some of these date back as far as 25,000 BC.

These small female figurines, made of stone and bone and clay and often referred to as Venus figures, have been found in areas where small settled communities once lived. They were often discovered lying close to the remains of the sunken walls of what were probably the earliest human-made dwellings on earth.

Niches or depressions had been made in the walls to hold the figures. These statues of women, some seemingly pregnant, have been found throughout the wide-spread Gravettian-Aurignacian sites in areas as far apart as Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Russia. These sites and figures appear to span a period of at least ten thousand years.

It appears highly probable that the female figurines were idols of a "great mother" cult, practiced by the non-nomadic Aurignacian mammoth hunters who inhabited the immense Eurasian territories that extended from Southern France to Lake Baikal area in Siberia.

THE ULTIMATE CONQUEST

"The earliest agriculture must have grown up around the shrines of the Mother Goddess, which thus became social and economic centers, as well as holy places and were the germs of future cities," writes Mellaart.

But just as the people of the early Neolithic cultures may have come down from Europe, as the possible descendants of the Gravettian-Aurignacian cultures, so later waves of even more northern peoples descended into the Near East. There has been some conjecture that these were the descendants of the Mesolithic (about 15,000-8000 BC), Maglemosian and Kunda cultures of northern Europe. Their arrival was not a gradual assimilation into the area, as the Goddess peoples' seems to have been, but rather a series of aggressive invasions, resulting in the conquest, area by area, of the Goddess people.

CATAL HUYUK

At the site that is now known as Jericho (in Canaan), by 7000 BC people were living in plastered brick houses, some with clay ovens with chimneys and even sockets for doorposts. Rectangular plaster shrines had already appeared.

Hacilar, some sixty miles from the Aurignacian site of Antalya, was inhabited at about 6000 BC. Here, too, figures of the Goddess have been found. And at the excavations at Catal Huyuk, close to the Cilician plains of Anatolia, near present day Konya, Mellaart discovered no less than forty shrines, dating from 6500 BC onward.

The culture of Catal Huyuk existed for nearly one thousand years. Mellaart reveals, "The statues allow us to recognize the main deities worshipped by neolithic people at Catal Huyuk. The principal deity was a goddess, who is shown in her three aspects, as a young woman, a mother giving birth or as an old woman."

Mellaart suggests that there may have been a majority of women at Catal Huyuk, as evidenced by the number of female burials. At Catal Huyuk too red ochre was strewn on the bodies; nearly all of the red ochre burials were of women. The religion was primarily associated with the role of women in the initial development of agriculture, and it seems extremely likely that the cult of the goddess was administered mainly by women.

AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

One of the most significant links between the two periods are the female figurines, understood in Neolithic societies, through their emergence into the historic period of written records, to represent the Goddess.

The sculptures of the Paleolithic cultures and those of the Neolithic periods are remarkably similar in materials, size and, most astonishing, in style. Hawkes commented on the relationship between the two periods, noting that the Paleolithic female figures ". . . are extraordinarily like the Mother or Earth Goddesses of the agricultural peoples of Eurasia in the Neolithic Age and must be directly ancestral to them."

Perhaps most significant is the fact that Aurignacian sites have now been discovered near Antalya, about sixty miles from the Neolithic Goddess-worshiping community of Hacilar in Anatolia (Turkey), and at Musa Dag in northern Syria (once a part of Canaan).

These Neolithic communities emerge with the earliest evidences of agricultural development (which is what defines them as neolithic). They appear in areas later known as Canaan (Palestine [Israel], Lebanon and Syria); in Anatolia (Turkey); and along the northern reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (Iraq and Syria).

THE INDO-EUROPEAN INVASIONS

These northern invaders, generally known as Indo-Europeans, brought their own religion with them, the worship of a young warrior god and/or a supreme father god. Their arrival is archaeologically and historically attested by 2400 BC, but several invasions may have occurred even earlier.

The pattern that emerged after the invasions was an amalgamation of the two theologies, the strength of one or the other often noticeably different from city to city.

As the invaders gained more territories and continued to grow more powerful over the next two thousand years, this synthesized religion often juxtaposed the female and male deities not as equals but with the male as the dominant husband or even as Her murderer. Yet myths, statues and documentary evidence reveal the continual presence of the Goddess and the survival of the customs and rituals connected to the religion, despite the efforts of the conquerors to destroy or belittle the ancient worship.

THE CLAN MOTHER

Russian paleontologist Z.A. Abramova, quoted in Alexander Marshak's recent book Roots of Civilization, offers a slightly different interpretation, writing that in the Paleolithic religion, "The image of the Woman-Mother . . . was a complex one, and it included diverse ideas related to the special significance of the women in early clan society. She was neither a god, an idol, nor the mother of a god; she was the Clan Mother . . . The ideology of the hunting tribes in this period of the matriarchal clan was reflected in the female figurines."

The connections between the Paleolithic female figurines and the later emergence of the Goddess-worshiping societies in the Neolithic periods of the Near and Middle East are not definitive, but are suggested by many authorities.

At the Gravettian site of Vestonice, Czechoslovakia, where Venus figures were not only formed but hardened in an oven, the carefully arranged grave of a woman was found. She was about forty years old. She had been supplied with tools, covered with mammoth shoulder blade bones and strewn with red ochre. In a proto-Neolithic site at Shanidar, on the northern stretches of the Tigris River, another grave was found, this one dating from about 9000 BC. It was the burial of a slightly younger woman, once again strewn with red ochre.

WRITTEN LANGUAGE

Although the earliest examples of written language yet discovered anywhere on earth appeared at the temple of the Queen of Heaven in Erech in Sumer, just before 3000 BC, writing at that time seems to have been used primarily for the business accounts of the temple.

The arriving northern groups adopted this manner of writing, known as cuneiform (small wedge signs pressed into damp clay) and used it for their own records and literature. Professor Chiera comments, "It is strange to notice that practically all the existing literature was put down in written form a century or two after 2000 BC."

Whether this suggests that written language was never considered as a medium for myths and legends before that time or that existing tablets were destroyed and rewritten at that time remains an open question. But unfortunately it means that we must rely on literature that was written after the start of the northern invasions and conquests.

THE ORIGIN OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION

Yet the survival and revival of the Goddess as supreme in certain areas, the customs, the rituals, the prayers, the symbolism of the myths as well as the evidence of temple sites and statues, provide us with a great deal of information on the worship of the Goddess even at that time. And to a certain extent, they allow us, by observing the progression of transitions that took place over the next two thousand years, to extrapolate backward to better understand the nature of the religion as it may have existed in earlier historic and Neolithic times.

The deification and worship of the female divinity in so many parts of the ancient world were variations on a theme, slightly differing versions of the same basic theological beliefs, those that originated in the earliest periods of human civilizations. It is difficult to grasp the immensity and significance of the extreme reverence paid to the Goddess over a period of either twenty-five thousand (as the Upper Paleolithic evidence suggests) or even seven thousand years and over miles of land, cutting across national boundaries and vast expanses of sea. Yet it is vital to do just that to fully comprehend the longevity as well as the widespread power and influence this religion once held.

THE WORSHIP

Much the same religion that Graves discusses existed even earlier in the areas known today as Iraq, Iran, India, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel (Palestine), Egypt, Sinai, Libya, Syria, Turkey, Greece and Italy as well as on the large island cultures of Crete, Cyprus, Malta, Sicily and Sardinia.

There were instances of much the same worship in the Neolithic periods of Europe, which began at about 3000 BC. The Tuatha de Danaan traced their origins back to a Goddess they brought with them to Ireland, long before the arrival of Roman culture.

The Celts, who now comprise a major part of the populations of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Brittany, were known to the Romans as the Gauls. They are known to have sent priests to a sacred festival for the Goddess Cybele in Pessinus, Anatolia, in the second century BC. And evidence of carvings at Carnac and the Gallic shrines of Chartres and Mont St. Michel in France suggests that these places were once sites of the Great Goddess.

Goddess

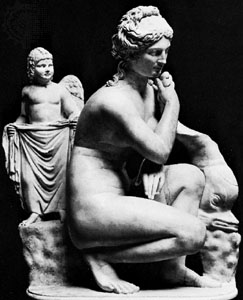

Aphrodite is the Ancient Greek goddess of beauty and love.

A goddess is a female deity.[1] Goddesses have been linked with virtues such as beauty, love, motherhood and fertility (Mother-goddess cult in prehistoric times). They have also been associated with ideas such as war, creation, and death.

In some faiths, a sacred female figure holds a central place in religious prayer and worship. For example, Shaktism, the worship of the female force that animates the world, is one of the three major sects of Hinduism. In Tibetan Buddhism, the highest advancement any person can achieve is to become like the great female Buddhas (e.g. Arya Tara), who are depicted as supreme protectors, fearless and filled with compassion for all beings.

The primacy of a monotheistic or near-monotheistic "Great Goddess" is advocated by some modern matriarchists as a female version of, preceding, or analogue to, the Abrahamic God associated with the historical rise of monotheism in the Mediterranean Axis Age.

Polytheist religions, including Polytheistic reconstructionists, honour multiple goddesses and gods, and usually view them as discrete, separate beings. These deities may be part of a pantheon, or different regions may have tutelary deities. The reconstructionists, like their ancient forebears, honour the deities particular to their country of origin.

Contents

[hide]

Etymology[edit]

The noun goddess is a secondary formation, combining the Germanic god with the Latinate -ess suffix. It first appeared in Middle English, from about 1350.[2] The English word follows the linguistic precedent of a number of languages—including Egyptian, Classical Greek, and several Semitic languages—that add a feminine ending to the language's word for god.

Earth or mother Goddesses[edit]

The head of an Egyptian goddess. The gender is suggested by the lack of a beard, and the simple hairstyle points to the divine status of the subject.

Joseph Campbell in The Power of Myth, a 1988 interview with Bill Moyers,[note 1] links the image of the Earth or Mother Goddess to symbols of fertility and reproduction.[3] For example, Campbell states that, "There have been systems of religion where the mother is the prime parent, the source... We talk of Mother Earth. And in Egypt you have the Mother Heavens, the Goddess Nut, who is represented as the whole heavenly sphere".[4] Campbell continues by stating that the correlation between fertility and the Goddess found its roots in agriculture:

- Bill Moyers: But what happened along the way to this reverence that in primitive societies was directed to the Goddess figure, the Great Goddess, the mother earth- what happened to that?

- Joseph Campbell: Well that was associated primarily with agriculture and the agricultural societies. It has to do with the earth. The human woman gives birth just as the earth gives birth to the plants...so woman magic and earth magic are the same. They are related. And the personification of the energy that gives birth to forms and nourishes forms is properly female. It is in the agricultural world of ancient Mesopotamia, the Egyptian Nile, and in the earlier planting-culture systems that the Goddess is the dominant mythic form.[5] Campbell also argues that the image of the Virgin Mary was derived from the image of Isis and her child Horus: "The antique model for the Madonna, is Isis with Horus at her breast".[6]

Historical polytheism[edit]

Ancient Near East[edit]

Mesopotamia[edit]

Inanna was the most worshipped goddess in ancient Sumer.[7][8] She was later syncretized with the East Semitic goddess Ishtar.[9] Other Mesopotamian goddesses include Ninhursag, Ninlil, Antu, Gaga

Ancient Africa (Egypt)[edit]

- Goddesses of the Ennead of Heliopolis: Tefnut, Nut, Nephthys, Isis

- Goddesses of the Ogdoad of Hermopolis: Naunet, Amaunet, Kauket, Hauhet; originally a cult of Hathor

- Satis and Anuket of the triad of Elephantine

Canaan[edit]

Goddesses of the Canaanite religion: Ba`alat Gebal, Astarte, Anat.

Anatolia[edit]

- Cybele: Her Hittite name was Kubaba, but her name changed to Cybele in Phrygian and Roman culture. Her effect can be also seen on Artemis as the Lady of Ephesus.

- Hebat: Mother Goddess of the Hittite pantheon and wife of the leader sky god, Teshub. She was the origin of the Hurrian cult.

- Arinniti: Hittite Goddess of the sun. She became patron of the Hittite Empire and monarchy.

- Leto: A mother Goddess figure in Lykia. She was also the main goddess of the capital city of Lykia League (Letoon)

Pre-Islamic Arabia[edit]

In pre-Islamic Mecca the goddesses Uzza, Manāt and al-Lāt were known as "the daughters of god". Uzzā was worshipped by the Nabataeans, who equated her with the Graeco-Roman goddesses Aphrodite, Urania, Venus and Caelestis. Each of the three goddesses had a separate shrine near Mecca. Uzzā, was called upon for protection by the pre-Islamic Quraysh. "In 624 at the battle called "Uhud", the war cry of the Qurayshites was, "O people of Uzzā, people of Hubal!" (Tawil 1993).

In fact, in ancient times, the goddess and god were known as Allat and Allah, or what would better be termed as deities representing "husband and wife".[10]

According to Ibn Ishaq's controversial account of the Satanic Verses (q.v.), these verses had previously endorsed them as intercessors for Muslims, but were abrogated. Most Muslim scholars have regarded the story as historically implausible, while opinion is divided among western scholars such as Leone Caetani and John Burton, who argue against, and William Muir and William Montgomery Watt, who argue for its plausibility.

Indo-European traditions[edit]

Pre-Christian and pre-Islamic goddesses in cultures that spoke Indo-European languages.

Indo-Iranian[edit]

Ushas is the main goddess of the Rigveda. Prithivi, the Earth, also appears as a goddess. Rivers are also deified as goddesses. Agneya or Aagneya is the Hindu Goddess of Fire. Varuni is the Hindu Goddess of Water. Bhoomi, Janani, Buvana, and Prithvi are names of the Hindu Goddess of Earth.

Greco-Roman[edit]

Statue of Ceres, the Romangoddess of agriculture

- Eleusinian Mysteries: Persephone, Demeter, Baubo

- Artemis: Goddess of the wilderness, wild animals, virginity, childbirth and the hunt.

- Aphrodite: Goddess of Love and Beauty.

- Athena: Goddess of crafts, strategy, wisdom and war. Athena is also a virgin goddess.

- Dione: An early chthonic goddess of prophesy.

- Eris: Goddess of chaos.

- Gaia: Primordial Goddess of the Earth. Most gods descend from her.

- Hecate: Goddess of sorcery, crossroads and magic. Often considered an chthonic or lunar goddess. She is either portrayed as a single goddess or a triple goddess (maiden, mother, crone).

- Hera: Goddess of family and marriage. She is the wife of Zeus and the queen of the Olympians. Mother of Ares.

- Hestia: Goddess of the hearth, home, domesticity, family and the state. Eldest sibling of Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hera and Demeter. Hestia is also a virgin goddess.

- Iris: Goddess of rainbows.

- Nike: Goddess of Victory. She is predominantly pictured with Zeus or Athena and sometimes Ares.

- Selene: Goddess of the Moon.

Celtic[edit]

Goddesses and Otherworldly Women in Celtic polytheism include:

- Celtic antiquity: Brigantia

- Gallo-Roman goddesses: Epona, Dea Matrona

- Irish mythology: Áine, Boann, Brigid, The Cailleach, Danu, Ériu, Fand and The Morrígan (Nemain, Macha, and Badb) among others.

The Celts honored goddesses of nature and natural forces, as well as those connected with skills and professions such as healing, warfare and poetry. The Celtic goddesses have diverse qualities such as abundance, creation and beauty, as well as harshness, slaughter and vengeance. They have been depicted as beautiful or hideous, old hags or young women, and at times may transform their appearance from one state to another, or into their associated creatures such as crows, cows, wolves or eels, to name but a few. In Irish mythology in particular, tutelary goddesses are often associated with sovereignty and various features of the land, notably mountains, rivers, forests and holy wells.[11]

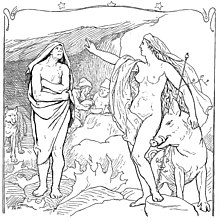

Germanic[edit]

The goddess Freyja is nuzzled by the boar Hildisvíni while gesturing to Hyndla (1895) by Lorenz Frølich.

Surviving accounts of Germanic mythology and Norse mythology contain numerous tales of female goddesses, giantesses, and divine female figures in their scriptures. The Germanic peoples had altars erected to the "Mothers and Matrons"and held celebrations specific to these goddeses (such as the Anglo-Saxon "Mothers-night"). Various other female deities are attested among the Germanic peoples, such as Nerthus attested in an early account of the Germanic peoples, Ēostre attested among the pagan Anglo-Saxons, and Sinthgunt attested among the pagan continental Germanic peoples. Examples of goddesses attested in Norse mythology include Frigg (wife of Odin, and the Anglo-Saxon version of whom is namesake of the modern English weekday Friday), Skaði (one time wife of Njörðr), Njerda (Scandinavian name of Nerthus), that also was married to Njörðr during Bronze Age, Freyja (wife of Óðr), Sif (wife of Thor), Gerðr (wife of Freyr), and personifications such as Jörð (earth), Sól (the sun), and Nótt (night). Female deities also play heavily into the Norse concept of death, where half of those slain in battle enter Freyja's field Fólkvangr, Hel's realm of the same name, and Rán who receives those who die at sea. Other female deities such as the valkyries, the norns, and the dísir are associated with a Germanic concept of fate (Old Norse Ørlög, Old English Wyrd), and celebrations were held in their honor, such as the Dísablót and Disting.

Pre-Columbian America[edit]

Aztec[edit]

Xochiquetzal (left) and Chalchiuhtlicue (right) as depicted in the Tovar Codex.

- Chalchiuhtlicue: goddess of water (rivers, seas, storms, etc.)

- Chantico: goddess of the hearth, flames

- Coyolxauhqui: warrior goddess associated with the moon

- Duality Earth Goddesses: Cihuacoatl (childbirth and maternal death), Coatlicue (earth as the womb and grave), Tlazolteotl (filth and purification)

- Itzpapalotl: monstrous ruler of Tamoanchan (a paradise realm)

- Mictecacihuatl: queen of Mictlan (the underworld)

- Xochiquetzal: goddess of fertility, beauty, and female sexual allure

Other[edit]

The Inca pantheon included: Pachamama, the supreme Mother Earth, Mama Killa, a moon goddess, and Mama Ocllo, a fertility goddess.

The main goddesses in the Maya pantheon were Ixchel, a mother goddess, and the Maya moon goddess. The Goddess I presided over eroticism, human procreation, and marriage. Ixtab was the goddess of suicide.

Folk religion and animism[edit]

African religions[edit]

In African and African diasporic religions, goddesses are often syncretized with Marian devotion, as in Ezili Dantor (Black Madonna of Częstochowa) and Erzulie Freda (Mater Dolorosa). There is also Buk, an Ethiopian goddess still worshipped in the southern regions. She represents the fertile aspect of women. So when a woman is having her period not only does it signify her submission to nature but also her union with the goddess.[citation needed] Another Ethiopian goddess is Atete—the goddess of spring and fertility. Farmers traditionally leave some of their products at the end of each harvesting season as an offering while their women sing traditional songs.

A rare example of henotheism focused on a single Goddess is found among the Southern Nuba of Sudan. The Nuba conceive of the creator Goddess as the "Great Mother" who gave birth to earth and to mankind.[12]

Chinese folk religion[edit]

- Mazu is the goddess of the sea who protects fishermen and sailors, widely worshipped in the south-eastern coastal areas of China and neighbouring areas in Southeast Asia.

- The Goddess Weaver Valentina, daughter of the Celestial Mother, wove the stars and their light, known as "the Silver River" (what Westerners call "The Milky Way Galaxy"), for heaven and earth. She was identified with the star Westerners know as Vega.[13]

Shintoism[edit]

Goddess Amaterasu is the chief among the Shinto Gods, while there are important female deities Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto, Inari and Konohanasakuya-hime.[citation needed]

Hinduism[edit]

The Hindu warrior goddess Durgakilling the buffalo-demon Mahishasura.

Hinduism is a complex of various belief systems that sees many gods and goddesses as being representative of and/or emanative from a single source, Brahman, understood either as a formless, infinite, impersonal monad in the Advaitatradition or as a dual god in the form of Lakshmi-Vishnu, Radha-Krishna, Shiva-Shakti in Dvaita traditions. Shaktas, worshippers of the Goddess, equate this god with Devi, the mother goddess. Such aspects of one god as male god (Shaktiman) and female energy (Shakti), working as a pair are often envisioned as male gods and their wives or consorts and provide many analogues between passive male ground and dynamic female energy.

For example, Brahma pairs with Sarasvati. Shiva likewise pairs with Parvati who later is represented through a number of Avatars (incarnations): Sati and the warrior figures, Durga and Kali. All goddesses in Hinduism are sometimes grouped together as the great goddess, Devi.

The Shaktis took a further step. Their ideology, based mainly on tantras, sees Shakti as the principle of energy through which all divinity functions, thus showing the masculine as depending on the feminine. In the great shakta scripture known as the Devi Mahatmya, all the goddesses are aspects of one presiding female force—one in truth and many in expression—giving the world and the cosmos the galvanic energy for motion. It expresses through philosophical tracts and metaphor, that the potentiality of masculine being is actuated by the feminine divine. More recently, the Indian author Rajesh Talwar has critiqued Western religion and written eloquently on the sacred feminine in the context of the North Indian Goddess Vaishno Devi.[14]

Local deities of different village regions in India were often identified with "mainstream" Hindu deities, a process that has been called Sanskritization. Others attribute it to the influence of monism or Advaita, which discounts polytheist or monotheist categorization.

While the monist forces have led to a fusion between some of the goddesses (108 names are common for many goddesses), centrifugal forces have also resulted in new goddesses and rituals gaining ascendance among the laity in different parts of Hindu world. Thus, the immensely popular goddess Durga was a pre-Vedic goddess who was later fused with Parvati, a process that can be traced through texts such as Kalika Purana (10th century), Durgabhaktitarangini (Vidyapati15th century), Chandimangal (16th century) etc.

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Judaism[edit]

According to Zohar, Lilith is the name of Adam's first wife, who was created at the same time as Adam. She left Adam and refused to return to the Garden of Eden after she mated with archangel Samael.[15] Her story was greatly developed, during the Middle Ages, in the tradition of Aggadic midrashim, the Zohar and Jewish mysticism.[16]

The Zohar tradition has influenced Jewish folkore, which postulates God created Adam to marry a woman named Lilith. Outside of Jewish tradition, Lilith was associated with the Mother Goddess, Inanna – later known as both Ishtar and Asherah. In The Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh was said to have destroyed a tree that was in a sacred grove dedicated to the goddess Ishtar/Inanna/Asherah. Lilith ran into the wilderness in despair. She then is depicted in the Talmud and Kabbalah as first wife to God's first creation of man, Adam. In time, as stated in the Old Testament, the Hebrew followers continued to worship "False Idols", like Asherah, as being as powerful as God. Jeremiah speaks of his (and God's) displeasure at this behavior to the Hebrew people about the worship of the goddess in the Old Testament. Lilith is banished from Adam and God's presence when she is discovered to be a "demon" and Eve becomes Adam's wife. Lilith then takes the form of the serpent in her jealous rage at being displaced as Adam's wife. Lilith as serpent then proceeds to trick Eve into eating the fruit from the tree of knowledge and in this way is responsible for the downfall of all of mankind. It is worthwhile to note here that in religions pre-dating Judaism, the serpent was associated with wisdom and rebirth (with the shedding of its skin).

The following female deities are mentioned in prominent Hebrew texts:

Christianity[edit]

Virgin Sophia design on a Harmony Society doorway in Harmony, Pennsylvania, carved by Frederick Reichert Rapp (1775–1834).

In Christianity, worship of any other deity besides the Trinity was deemed heretical. The veneration of Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, as an especially privileged saint has continued since the beginning of the Catholic faith.[citation needed]Mary is venerated as the Mother of God, Queen of Heaven, Mother of the Church, Our Lady, Star of the Sea, and other lofty titles. Marian devotion similar to this kind is also found in Eastern Orthodoxy and sometimes in Anglicanism, though not in the majority of denominations of Protestantism. That being said, the Virgin Mary is not a goddess.

In some Christian traditions (like the Orthodox tradition), Sophia is the personification of either divine wisdom (or of an archangel) that takes female form. She is mentioned in the first chapter of the Book of Proverbs. Sophia is identified by some as the wisdom imparting Holy Spirit of the Christian Trinity, whose names in Hebrew—Ruach and Shekhinah—are both feminine, and whose symbol of the dove was commonly associated in the Ancient Near East with the figure of the Mother Goddess.

In Mysticism, Gnosticism, as well as some Hellenistic religions, there is a female spirit or goddess named Sophia who is said to embody wisdom and who is sometimes described as a virgin. In Roman Catholic mysticism, Saint Hildegardcelebrated Sophia as a cosmic figure both in her writing and art. Within the Protestant tradition in England, 17th century the mystic universalist and founder of the Philadelphian Society Jane Leade wrote copious descriptions of her visions and dialogues with the "Virgin Sophia" who, she said, revealed to her the spiritual workings of the universe. Leade was hugely influenced by the theosophical writings of 16th century German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme, who also speaks of the Sophia in works such as The Way to Christ.[17] Jakob Böhme was very influential to a number of Christian mystics and religious leaders, including George Rapp and the Harmony Society.

Feminism[edit]

Roman, Hadrianic period, statue of Isisin marble from the Musei Capitolini.

Goddess movement[edit]

At least since first-wave feminism in the United States, there has been interest in analyzing religion to see if and how doctrines and practices treat women unfairly, as in Elizabeth Cady Stanton's The Woman's Bible. Again in second-wave feminism in the U.S., as well as in many European and other countries, religion became the focus of some feminist analysis in Judaism, Christianity, and other religions, and some women turned to ancient goddess religions as an alternative to Abrahamic religions (Womanspirit Rising 1979; Weaving the Visions 1989). Today both women and men continue to be involved in the Goddess movement (Christ 1997). The popularity of organizations such as the Fellowship of Isis attest to the continuing growth of the religion of the Goddess throughout the world.

While much of the attempt at gender equity in mainstream Christianity (Judaism never recognized any gender for God) is aimed at reinterpreting scripture and degenderizing language used to name and describe the divine (Ruether, 1984; Plaskow, 1991), there are a growing number of people who identify as Christians or Jews who are trying to integrate goddess imagery into their religions (Kien, 2000; Kidd 1996,"Goddess Christians Yahoo Group").

Sacred feminine[edit]

The term "sacred feminine" was first coined in the 1970s, in New Age popularizations of the Hindu Shakti. Hinduism also worships multitude of goddesses that have their important role and thus in all came to interest for the New Age, feminism and lesbian feminism movements.[18]

Metaphorical use[edit]

The term "goddess" has also been adapted to poetic and secular use as a complimentary description of a non-mythological woman.[19] The OED notes 1579 as the date of the earliest attestation of such figurative use, in Lauretta the diuine Petrarches Goddesse.

Shakespeare had several of his male characters address female characters as goddesses, including Demetrius to Helena in A Midsummer Night's Dream ("O Helen, goddess, nymph, perfect, divine!"), Berowne to Rosaline in Love's Labour's Lost ("A woman I forswore; but I will prove, Thou being a goddess, I forswore not thee"), and Bertram to Diana in All's Well That Ends Well. Pisanio also compares Imogen to a goddess to describe her composure under duress in Cymbeline.

Neopaganism[edit]

Most Modern Pagan traditions honour one or more goddesses. Wicca has a duotheistic belief system, consisting of a single goddess and a single god, who in hieros gamos represent a united whole.

Wicca[edit]

The lunar Triple Goddess symbol.

In Wicca "the Goddess" is a deity of prime importance, along with her consort the Horned God. Within many forms of Wicca the Goddess has come to be considered as a universal deity, more in line with her description in the Charge of the Goddess, a key Wiccan text. In this guise she is the "Queen of Heaven", similar to Isis. She also encompasses and conceives all life, much like Gaia. Similarly to Isis and certain late Classical conceptions of Selene, she is the summation of all other goddesses, who represent her different names and aspects across the different cultures. The Goddess is often portrayed with strong lunar symbolism, drawing on various cultures and deities such as Diana, Hecate, and Isis, and is often depicted as the Maiden, Mother and Crone triad popularised by Robert Graves (see Triple Goddess below). Many depictions of her also draw strongly on Celtic goddesses. Some Wiccans believe there are many goddesses, and in some forms of Wicca, notably Dianic Wicca, the Goddess alone is worshipped, and the God plays very little part in their worship and ritual.

Goddesses or demi-goddesses appear in sets of three in a number of ancient European pagan mythologies; these include the Greek Erinyes (Furies) and Moirai (Fates); the Norse Norns; Brighid and her two sisters, also called Brighid, from Irish or Celtic mythology.

Robert Graves popularised the triad of "Maiden" (or "Virgin"), "Mother" and "Crone", and while this idea did not rest on sound scholarship, his poetic inspiration has gained a tenacious hold. Considerable variation in the precise conceptions of these figures exists, as typically occurs in Neopaganism and indeed in pagan religions in general. Some choose to interpret them as three stages in a woman's life, separated by menarche and menopause. Others find this too biologically based and rigid, and prefer a freer interpretation, with the Maiden as birth (independent, self-centred, seeking), the Mother as giving birth (interrelated, compassionate nurturing, creating), and the Crone as death and renewal (holistic, remote, unknowable) — and all three erotic and wise.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ First broadcast on PBS in 1988 as a documentary, The Power of Myth was also released in the same year as a book created under the direction of the late Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Ellwood, Robert S. (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions(Rev. ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 181. ISBN 1438110383.

- Jump up^ Barnhart (1995:323).[incomplete short citation]

- Jump up^ "Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth - Season 1, Episode 5: Love and the Goddess - TV.com". TV.com. CBS Interactive.

- Jump up^ p. 165, 1988, first edition[incomplete short citation]

- Jump up^ pp.166–7, (1988, first edition)[incomplete short citation]

- Jump up^ p. 176, 1988, first edition[incomplete short citation]

- Jump up^ Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York City, New York: Harper&Row Publishers. p. xviii. ISBN 0-06-090854-8.

- Jump up^ Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Daily Life. Greenwood. p. 182. ISBN 978-0313294976.

- Jump up^ Collins, Paul (1994). "The Sumerian Goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC)". Papers of from the Institute of Archaeology. 5. UCL. pp. 110–111.

- Jump up^ "Allah, Divine or Demonic? Chapter Fifteen". Balaams-ass.com. 1984-06-01. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- Jump up^ Wood, Juliette (2001). The Celts: Life, Myth, and Art (New ed.). London: Duncard Baird Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 9781903296264.

- Jump up^ Mbiti, John S. (1991). Introduction to African Religion (2nd rev. ed.). Oxford, England: Heinemann Educational Books. p. 53. ISBN 9780435940027.

- Jump up^ Chang, Jung (2003). Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China(reprint ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 429. ISBN 1439106495. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Jump up^ http://www.kalpazpublications.com/index.php?p=sr&Uc=9788178355900&l=0

- Jump up^ "Samael & Lilith - Unexplained - IN SEARCH FOR TRUTH". rin.ru.

- Jump up^ Schwartz, Howard (2004). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0195358708.

- Jump up^ Böhme, Jacob (1622). The Way to Christ. William Law (trans.). Pater-noster Row, London: M. Richardson.

- Jump up^ Kinsley, David (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780520908833. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Jump up^ OED: "Applied to a woman. one's goddess: the woman whom one ‘worships’ or devotedly admires."[incomplete short citation]

Further reading[edit]

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins, and Victor Mair (2010). Sacred Display: Divine and Magical Female Figures of Eurasia. Cambria Press.

- Barnhart, Robert K (1995). The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology: the Origins of American English Words. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-270084-7

- Gorshunova . Olga V.(2008), Svjashennye derevja Khodzhi Barora…, ( Sacred Trees of Khodzhi Baror: Phytolatry and the Cult of Female Deity in Central Asia) in Etnoragraficheskoe Obozrenie, n° 1, pp. 71–82. ISSN 0869-5415. (in Russian).