The Saturn theory

(PDF version of this article)

“The inertia of the human mind and its resistance to innovation are most clearly demonstrated not, as one might expect, by the ignorant mass — which is easily swayed once its imagination is caught — but by professionals with a vested interest in tradition and in the monopoly of learning. Innovation is a twofold threat to academic mediocrities: it endangers their oracular authority, and it evokes the deeper fear that their whole, laboriously constructed intellectual edifice might collapse. The academic backwoodsmen have been the curse of genius from Aristarchus to Darwin and Freud; they stretch, a solid and hostile phalanx of pedantic mediocrities, across the centuries.” (Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers [New York, 1959], p. 427.)

The so-called “Saturn Theory” originated with David Talbott who, in the mid-1970’s, began investigating clues that the planet Saturn formerly played a significant role in recent Earth history, a history hinted at in certain ancient mythological traditions. A cornerstone of Talbott’s reasoning was the singular insight that myths of Creation reflected eyewitness accounts of extraordinary planetary cataclysms in the circumpolar sky. More specifically, Talbott concluded that the ancients’ collective testimony pointed to the former presence of a unique configuration of planets suspended over the Earth’s North Pole—a polar configuration, as it were—involving Saturn, Venus, and Mars (among other celestial bodies). Talbott’s researches eventually culminated in the groundbreaking book The Saturn Myth (Doubleday, 1980), which, in turn, inspired Dwardu Cardona and myself to launch similar studies. Cardona went on to publish numerous articles and a handful of voluminous works on the subject, arguing that various aspects of Earth-geology could only be explained by the near-presence of a giant body such as Saturn over the North Pole (see Primordial Star among other works).

My own involvement with the project was three-fold: (1) During the early 80’s, Dave and I worked in close collaboration on a series of articles for Kronos and other publications, outlining Venus’s role in these cataclysmic events; (2) In 1988, Dave launched the journal Aeon to serve as the primary research organ for exploring the manifold aspects of the Saturn theory. At the time I served as chief editor and was a frequent contributor; (3) From 1980 to the present, I devoted the majority of my time and energy to reconstructing certain key phases in the evolutionary history of the polar configuration, much of which involved deciphering and carefully dileneating the specific roles of the planets Venus and Mars in this game of planetary billiards played out on the celestial landscape. The rest, as they say, is history—or pure fiction, according to our many critics and detractors. Looking back on the results of my nearly four-decade long collaboration with Dave, I can say with a large measure of confidence that I fully expect our findings with respect to the recent catastrophic roles of neighboring planets in Earth history will eventually be confirmed and in spades. To paraphrase Sherlock: Come along, dear reader, the revolution is afoot!

A brief summary of the Saturn theory follows:

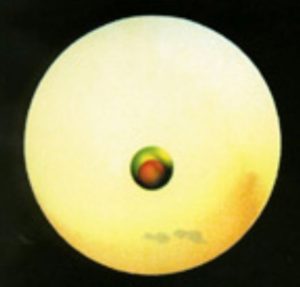

The Saturn theory offers a radically different approach to understanding the recent history of the solar system.1 Briefly summarized, the theory posits that the neighboring planets only recently settled into their current orbits, the Earth formerly being involved in a unique planetary configuration of sorts together with Saturn, Venus, and Mars. As the terrestrial skywatcher looked upwards, he saw a spectacular and awe-inspiring apparition dominating the celestial landscape. At the heart of heaven the massive gas giant Saturn appeared fixed atop the North polar axis, with Venus and Mars set within its center like two concentric orbs (see figure one, where Venus is the green orb and Mars the innermost red orb). The theory holds that the origin of ancient myth and religion—indeed the origin of the primary institutions of civilization itself—is inextricably linked to the appearance and evolutionary history of this unique congregation of planets.

How does one go about documenting this extraordinary claim? Extraordinary claims, it is said, require extraordinary evidential support in order to believed. While I believe the Saturn theory can meet this crucial test, it goes without saying that a discussion of the various lines of evidence pointing to the polar configuration would require several volumes in order to make a fully compelling case. In this brief overview I can do no more than offer a small sampling of the relevant evidence.

If the truth be known, the Saturn theory suffers from an embarrassment of riches with respect to evidence which supports the central tenets of the theory. Early descriptions of the “sun” and various planets from Mesopotamia and elsewhere describe them as occupying “impossible” positions and moving in a manner which defies astronomical reality (as currently understood, that is). The ancient sun god, for example, is said to “rise” and “set” at the heart of heaven upon a sacred mountain. The planet Venus is described as standing at the “heart of heaven” or within the crescent of Sin. Mars is pointed to as a principal cause of “eclipses” and other natural disasters.2 While not one of these scenarios is possible given the current order of the solar system, each is consistent with the history of the respective planets in the polar configuration as reconstructed by Talbott and myself.

The testimony from ancient myth and folklore is adamant that the respective planets once moved on radically different orbits and rained catastrophe from the skies, even if that message has been overlooked and “ostrachized”3 by virtually everyone. Thus, numerous cultures tell of the time when different suns ruled the heavens. This belief was especially common in the New World: “The idea that the sun was not eternal was shared by other American Indian tribes so widely that we consider it must have been part of their belief long before any high culture had arisen in the Americas.”4

The Popol Vuh, lauded as the “Mayan Bible,” attests to the same idea. There a previous sun god is described as follows:

“Like a man was the sun when it showed itself…It showed itself when it was born and remained fixed in the sky like a mirror. Certainly it was not the same sun which we see, it is said in their old tales.”5

Equally widespread are traditions which report that a dragon-like monster once eclipsed the sun and brought the world to the brink of destruction. Countless cultures preserve memory of the terrifying time when Venus assumed a serpentine form6, or when a spectacular conjunction of planets dominated the celestial landscape.7 Such traditions can be documented from one culture to another and, upon systematic analysis, reveal numerous analogous structural details, a telltale sign that they were inspired by common experience of spectacular celestial events rather than creative imagination and fantasy.

In addition to the remarkably detailed and consistent testimony from ancient myth and folklore, the artistic record likewise provides compelling evidence that the planets only recently moved on radically different orbits. Consider, for example, the three images depicted in figure two. As I have documented8, such images are ubiquitous in the prehistoric rock art of every inhabited continent. Hitherto they have been interpreted as drawings of the Sun by virtually all leading authorities on ancient art and religion, this despite the fact that they do not have any obvious resemblance to the current solar orb.

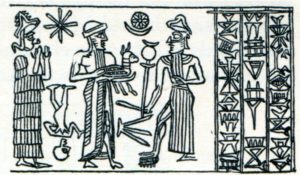

It is noteworthy that the ancient sun-god was depicted in the very same manner by the earliest civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Figure three, for example, shows an Akkadian seal in which the Shamash disc is represented as an “eye-like” object, as in the first image in figure two. Figure four shows the Shamash disc as an eight-pointed star or wheel. Figure five shows the Shamash disc as an eight-petalled flower. Numerous other variations upon these common themes could be provided, all impossible to reconcile with the appearance of the current solar orb.

It is at this point that the researcher is presented with a theoretical dilemma, the successful resolution of which promises to unlock the secrets of our prehistoric past. If one chooses to dismiss the specific and consistent imagery associated with these ancient solar images as the product of creative imagination—the typical approach of conventional art historians—one is also forced to dismiss the equally widespread testimony that different suns prevailed in ancient times. This approach has little to recommend it, for it involves nothing less than turning a deaf ear to the testimony of our ancestors and, in any case, has thus far produced precious few insights into the origin of ancient symbolism.

The alternative is equally unthinkable, for it involves accepting these endlessly repeated images as accurate drawings of the ancient “sun”, albeit one different in nature and appearance than that currently prevailing. As bizarre as this possibility appears at first glance, it does have much to recommend it. The ancient Babylonians were careful to distinguish Shamash from the current sun, identifying the god with the distant planet Saturn.9 It was this little-known datum which led Velikovsky to consider the possibility that Saturn formerly appeared more prominent, perhaps even serving as a sun-like object for the satellite Earth.10 Velikovsky’s seminal insight, in turn, served as the theoretical foundation for the subsequent researches of Talbott, Cardona, myself and others who succeeded in documenting the basic claim that Saturn once dominated the heavens, a fact reflected in the otherwise puzzling prominence accorded this planet in the earliest pantheons

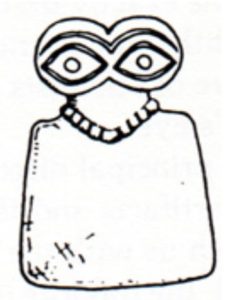

Further support for the alternative “Saturn theory” comes upon considering the representation of the planet Venus in ancient art. A straightforward interpretation of the various images superimposed upon the “solar” disc in figure two would understand the first as an “eye”; the second as an eight-spoked wheel or “star”; and the third as an eight-petalled flower. Now it is a remarkable fact that the planet Venus is consistently associated with these very forms from one ancient culture to another. The ancient Sumerians, for example, represented Venus (as Inanna) as an eye-goddess, eight-pointed star, and eight-petalled flower or rosette. Consider the figurine represented in figure six, one of thousands discovered by Max Mallowan during his excavations of the Inanna-precinct at Uruk. Similar “eye-goddesses” have been found throughout the ancient world, from Neolithic Europe to India. Figure seven shows an early cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3000 BCE), depicting Inanna as an “eye-goddess” alongside her familiar eight-petalled rosette.

The very same images are prominent in the sacred iconography surrounding the Akkadian Ishtar. Thus, figure eight shows Ishtar/Venus together with an eight-spoked wheel, while figure nine shows Ishtar/Venus together with an eight-pointed star. Figure ten shows Ishtar in conjunction with a rosette-like star.

The fact that the planet Venus was associated with the very same forms in Mesoamerica, where the observation and worship of that planet formed an obsession, strongly supports the conclusion that such images have their origin in the ancient appearance of the planet. The same conclusion is supported by the fact that cultures as disparate as those of the Australian aborigines, Maya, Polynesians, and Chinese described Venus by epithets signifying “Great Eye,” “Great Star,” and “luminous flower.”11

How are we to explain this curious state of affairs whereby Venus is associated with the very symbols seemingly depicted in prehistoric “sun”-images? Surely not by reference to the current solar system, for Venus does not even vaguely resemble an “eye,” eight-pointed “star,” or “flower.” Yet if Venus only recently appeared superimposed against the backdrop of Saturn/Shamash, as per the reconstruction offered by Talbott and myself in figure one, the mystery is explained at once. Subsequently, upon further evolution of the polar configuration, Venus assumed a radiant appearance, sending forth streamers across the face of the ancient sun-god (see figure eleven). This situation is reflected in the latter two images in figure three.

Planets in Ancient Lore

At the turn of the century it was widely held that the central themes of the most ancient myths, telling of the Creation, Deluge, Golden Age, Dragon combat, etc. were all “nature” myths describing the stereotypical behavior of the two primary celestial bodies, typically in allegorical or euhemeristic fashion.12 The Saturn theory offers a very similar conclusion, with the all-important proviso that the planets formerly dominated the celestial landscape rather than the current Sun and Moon.

That the earliest gods and mythical figures of the various cultures are celestial in nature is easily shown. The Sumerian goddess Inanna, explicitly identified with the planet Venus already at the dawn of the historical period (c. 3300 BCE), is a case in point and might well serve as an exemplar for comparative analysis. Virtually every ancient culture will feature a goddess with notable structural affinities to Inanna, although the identification with Venus is not always preserved. The Skidi Pawnee Indians of the American central plains, for example, celebrate the wondrous deeds of the primeval goddess cu-piritta-ka, identified with Venus.13 It was her union with the warrior-god u-pirikucu, explicitly identified with the planet Mars, which signaled the crowning event of Creation:

“The second god Tirawahat placed in the heavens was Evening Star, known to the white people as Venus…She was a beautiful woman. By speaking and waving her hands she could perform wonders. Through this star and Morning Star [Mars] all things were created. She is the mother of the Skiri.”14

As the Skidi traditions attest, the planet Mars played a prominent role in ancient myth and religion. Wherever one looks, one will find the red planet accorded a numinous power seemingly out of proportion to its present modest appearance. The Sumerian war-god Nergal, early on identified with the planet Mars, forms a pivotal figure in comparative analysis. Thus, it can be shown that war-gods and warrior-heroes from every corner of the globe share numerous characteristics in common with the Sumerian god, including some of a strikingly specific nature.15 To take but one mythical theme of hundreds available: The Makiritare Indians of the Amazonian rain forest tell of the time when the hero Ahishama, identified with the red planet, climbed a giant stairway to the sky.16 The fact that a very similar story was related of Nergal in ancient Mesopotamia17 suggests that the mythical theme originated in objective historical events involving the red planet.18 Yet one looks in vain for a satisfactory explanation of this particular mythical theme given the current order of the solar system, wherein a celestial stairway is not to be found. Neolithic rock art, however, offers countless examples of “stairway”-like appendages extending from the ancient sun god, thereby complementing and helping to illuminate the universal myth of a luminous stairway spanning the heavens (See figure twelve). If we are to be faithful to the evidence, the most logical conclusion is that the stairway to heaven was a visible apparition associated with the ancient sun god during a particular phase of the polar configuration.

Towards a Science of Mythology

In an attempt to develop a rigorous scientific methodology for the study of ancient myth, the Saturnists would offer a series of basic groundrules deemed to be essential if researchers are to discover the original significance and fundamental message of ancient mythical traditions. First and foremost, perhaps, is the general proposition that ancient myth constitutes an invaluable and generally trustworthy source for reconstructing a valid history of our solar system. Far from being a leap of faith, this fundamental finding of the Saturn theory derives from several decades of extensive research into ancient myth and can be demonstrated using the normal methods of logic and evidence

A second basic tenet would emphasize the comparative method. Simply stated, no ancient myth or primary cultural institution is fully understandable in isolation. Egyptian myth, to take but one example, is essentially incomprehensible apart from detailed analysis of analogous themes and motifs from ancient Mesopotamia and the New World, both of which provide the indispensable link to the early astronomical traditions that are all but lost in Egypt itself (Horus’s identification with the Morning Star and Mars offers a notable exception in this regard and forms a close analogue to the Pawnee traditions surrounding the red planet). Hathor’s identification with the “Eye of Ra,” for example, can only be understood by reference to the widespread idea whereby Venus once formed the central “eye” of the ancient sun god. Note further that Hathor’s name, which signifies “House of Horus,” captures perfectly the essence of the relationship of Venus and Mars as illustrated in figure one. The planet-goddess Hathor, as the “Eye of Ra,” literally housed the warrior Horus.

A third basic tenet of the Saturn theory holds that ancient myth and ritual typically commemorate extraordinary events witnessed by human beings. If myth constitutes a creative interpretation of the traumatic celestial events in pseudo-historical terms—the flooding of the world, a great hero’s consorting with a beautiful goddess—ritual originated as a purposeful and remarkably faithful attempt to reenact the fateful events in question. Mars’ climbing of the celestial stairway, for example, was reenacted in countless sacred rites throughout the ancient world.19 The archetypal rite of the sacred marriage, attested already at the dawn of history in Mesopotamia, purports to commemorate the king’s union with the planet Venus (Inanna). The original inspiration for this bizarre rite, as I have theorized, was the spectacular conjunction of Venus and Mars in prehistoric times.20

A fourth basic tenet of the Saturn theory holds that historical evidence together with consistent (or widespread) human testimony must be given credence, even if a ready explanation of such testimony is not immediately obvious or appears to contradict current scientific opinion. Velikovsky’s admonition in the preface to Worlds in Collision serves as a rallying cry here: “If, occasionally, historical evidence does not square with formulated laws, it should be remembered that a law is but a deduction from experience and experiment, and therefore laws must conform with historical facts, not facts with laws.”

The famous controversy over the likelihood that rocks (meteors) could fall from the sky, a possibility denied by several of the best minds of the 18th and 19th centuries, might well serve as a prototype here. Formerly dismissed as too ridiculous to merit serious discussion, the fact that meteorites occasionally fall to Earth from heaven was perfectly well known to the ancient Sumerians. All but lost for several millennia, such knowledge is once again commonplace amongst schoolboys everywhere.

Equally instructive is the on-going controversy over the possibility that rocks from Mars could somehow find their way to the Earth, fervently denied by various leading authorities until quite recently (c. 1987). The eventual triumph of the Martian meteorite hypothesis is yet another classic example of the leading paradigms of the modern scientific Age being instantly overturned by a series of anomalous findings.21 Such examples could be multiplied ad infinitum. Science, much like religion, proves to be notoriously malleable in this regard: What is considered impossible or fantastic by one generation might well come to be accepted by future generations unencumbered by similar prejudices.

A fifth basic tenet of the Saturn theory holds that recurring anomalies in ancient myth and tradition offer a key to discovery. Certainly it is most unlikely that one culture would invent traditions of fire-breathing dragons (or witches) that once threatened to eclipse the ancient sun god. Yet one finds the very same improbable motif from one ancient culture to another, yet another sure indication that common experience of spectacular celestial events holds the key to a scientific analysis of ancient mythical traditions.

A sixth central tenet of the Saturn theory holds that the history and evolution of the polar configuration constitutes nothing less than the history of the gods. The “birth” of the warrior-hero, the war-like rampage of the mother goddess, the “death” or “eclipse” of the primeval sun god—and a thousand different themes alike—all have their inspiration in the spectacular events associated with the evolution of the polar configuration.

A seventh basic tenet of the Saturn theory holds that future discoveries vis a vis the geology and geomorphology of the respective planets will act to either support or undermine the model. For it stands to reason that, if the extraordinary events described here have any basis in reality, such events must have left an indelible mark on the planets that participated in the polar configuration. It is also expected that some of these telltale signs of participation in the polar configuration will prove to be difficult, if not impossible, to explain by any other model.

A Fundamental Objection to the Saturn Theory

The most obvious objection to the Saturn theory is its apparent incompatibility with conventional astrophysics. This is indeed a formidable objection, one deserving of serious attention and, ultimately, a valid answer, ideally in terms of offering a viable physical model for the polar configuration. While promising steps towards achieving a viable physical model have been achieved (the models of Thornhill and Peratt, for example), much work remains to be done in this area, preferably by scientists trained in the requisite fields of astronomy, physics, and mechanics. Personally, I remain confident that an answer will be found if for no other reason than that it is highly improbable that a theory with so much historical evidence in its favor could prove entirely illusory.

If the history of science teaches us anything, it is that there is ample precedent for reserving judgment on an historical thesis well supported by evidence but lacking a viable physical model. Darwin’s theory of evolution, to take a particularly notorious example, languished for decades under the objection that it lacked a viable model of heredity which could explain how the much needed genetic changes could originate and come to be fixed (rather than blended, as per earlier models of heredity). Already by the time of Darwin, there was a wealth of evidence that evolution had occurred—how else are we to explain the fact that modern whales occasionally show traces of vestigial hind limbs and hip girdles?—but a viable model of heredity was not yet at hand, to say nothing of a chemical model for genetic mutation or embryonic differentiation. Even today, well over a hundred years later, many of the most fundamental questions surrounding the biochemical mechanisms of evolution remain unanswerable. We still have little understanding of how the various phyla originated or why some species proved successful while others became extinct. In the meantime, however, while modern biology awaits a solution to these truly perplexing and formidable mysteries, no informed scientist can doubt the historical reality that biological evolution has occurred. The question is how did life evolve and by what precise means? A similar situation surrounds the Saturn theory, in my opinion. Here, too, the historical evidence is unequivocal that various planets once participated in a polar configuration and wrecked havoc with the inner solar system. The question is how we are to understand this history from the standpoint of physics?

Footnotes

- It will be noted that I do not presume to speak for David Talbott or Dwardu Cardona, the two senior pioneers in this field of study.

- For a thorough discussion of these issues, see E. Cochrane, Martian Metamorphoses (Ames, 1997).

- This word, coined by Samuel Butler, describes the propensity of some to stick their heads in the sand in order to ignore the obvious.

- C. Burland, The Gods of Mexico (New York, 1967), p. 140.

- D. Goetz & S. Morley, Popol Vuh (Norman, 1972), p. 188.

- I. Velikovsky, Worlds in Collision (New York, 1950), pp. 162-191; D. Talbott, “The Comet Venus,” Aeon 3:5 (1994), pp. 5-51; D. Cardona, “Cometary Venus,” in D. Pearlman ed., Stephen J. Gould and Immanuel Velikovsky(Forest Hills, 1996), pp. 442-466; E. Cochrane, “On Comets and Kings,” Aeon2:1 (1989), pp. 53-75.

- See the discussion in D. Pankenier, “The Bamboo Annals Revisited…Chronology of Early Zhou, Part 1,” BSOAS 55 (1992), p. 281.

- E. Cochrane, “Suns and Planets in Neolithic Rock Art,” Aeon 3:2 (1993), pp. 51-63; see also the discussion in E. Cochrane, “Venus, Mars…and Saturn,” Chronology and Catastrophism Review (1998:2), pp. 16-20.

- Already common knowledge by the time of the astronomical reports sent to Assurbanipal and other Assyrian kings (c. 700 BCE), the identification of Saturn and Shamash likely goes back to the first systematic attempts at monitoring the heavens. See here the discussion in U. Koch-Westenholz, Mesopotamian Astrology (Copenhagen, 1995), pp. 122-123.

- I. Velikovsky, Mankind in Amnesia (Garden City, 1982), pp. 99ff.

- E. Cochrane, “Suns and Planets in Neolithic Rock Art,” Aeon 3:2 (1993), pp. 51-63.

- The so-called solar school of mythology championed by F.M. Muller and others.

- J. Murie, “Ceremonies of the Pawnee,” Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 27 (Cambridge, 1981), p. 39.

- Ibid.

- See E. Cochrane, Martian Metamorphoses: The Planet Mars in Ancient Myth and Religion (Ames, 1997).

- M. de. Civrieux, Watunna: An Orinoco Creation Cycle (San Francisco, 1980), pp. 113-114.

- S. Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia (Oxford, 1991), p. 171. See also the discussion in E. von Weiher, Der babylonische Gott Nergal (Berlin, 1971), p. 52; J. V. Wilson, The Rebel Lands (London, 1979) p. 98; and O. Gurney, “The Sultantepe Tablets,” Anatolian Studies 10 (1960), pp. 125, 130.

- E. Cochrane, “The Stairway to Heaven,” Aeon 5:1 (1997), pp. 69-78.

- See, for example, the numerous rites involving the symbolic ascent of the polar axis or World Tree in M. Eliade, Shamanism (Princeton, 1964), pp. 487-494.

- E. Cochrane, “The Female Star,” Aeon 5:3 (1998), pp. 49-64.

- See the discussion in E. Cochrane, “Martian Meteorites in Ancient Myth and Modern Science,” Aeon 4:2 (1995), pp. 57-73.