Rough Notes:

Credit: NASA/HST

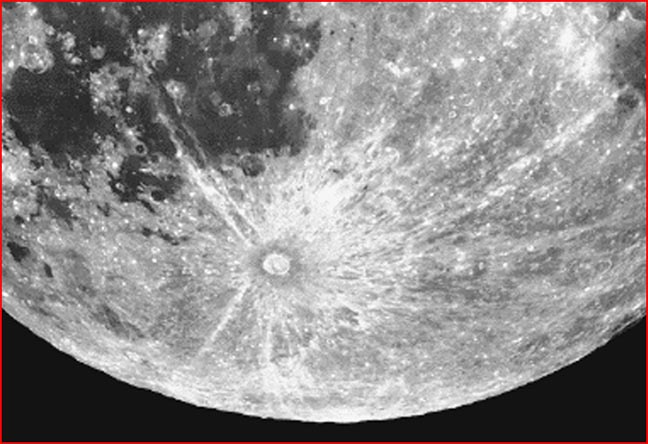

Of all the features on the lunar landscape that are commonly identified as “impact craters”,

the most prominent is the crater Tycho in the Southern hemisphere.

Mar 08, 2006

Lunar Craters—a Failed Theory

When seeking to test a hypothesis, it is helpful to start with clear and undeniable facts. But when the impact theory is applied to the prominent lunar “rayed crater”, Tycho, the theory fails even the most obvious tests.

Certainly the most conspicuous crater on the Moon is Tycho in the southern hemisphere. (For context, we have placed a full Hubble Telescope image of the Moon here). The crater is some 85 kilometers in diameter, displaying enigmatic “rays” that extend at least a quarter of the way around the moon.

The central peak, said to have been formed by a “rebound” of subterranean material, rises about 2 kilometers above the crater floor. Planetary scientists suggest that the flat floor of the crater (seen here) was formed by the pooling of melted material.

But the idea that an impact would create such an extensive pool of molten rock finds no support in impact experiments or in high-energy explosions. Not even an atomic explosion creates a flat melted floor of this sort. The force of the explosion shocks and ejects material. It does not hold the material in place to “melt” it into a lake of lava.

When the brilliant engineer, Ralph Juergens, considered the lunar craters Tycho and Aristarchus, he noted the distinct features of electrical discharge. He wrote in 1974, “…If Aristarchus and Tycho were produced by electric discharges, their clean floors would be just about what one would expect. The abilities of discharges to produce melting on cathode [negatively charged] surfaces and generally to ‘clean up’ those surfaces have been remarked upon since the earliest experiments with electric discharges”.

Juergens envisioned an interplanetary arc between the Moon and an approaching body (for his analysis, he summoned the planet Mars). While an instantaneous explosion does not have time to create a lava lake, an electric arc involving a long-distance flow of current between two approaching bodies, “would persist beyond the instant of any initial touchdown explosion”, leaving material melted in place.

Juergens saw Tycho as a “cathode crater”, and he drew special attention to Tycho’s “spectacular system of rays”. These, he suggested, are the very kind of streamers an electrical theorist would look for—a signature of the electron pathways that triggered the Tycho discharge.

Of course, the astronomers’ consensus today is that the streamers are the trails of material ejected from the crater into narrow paths over extraordinary distances. But the “rays”, Juergens noted, have no discernible depth, while material exploding from a Tycho-sized crater “would at least occasionally fall more heavily in one place than in another and build up substantial formations. But no one has ever been able to point out such a ray ‘deposit’”.

The presence of the narrow rays over such long distances, according to Juergens, is “all-but-impossible to reconcile with ejection origins. Enormous velocities of ejection must be postulated to explain the lengths of the rays, yet the energetic processes responsible for such velocities must be imagined to be focused very precisely to account for the ribbon-thin appearance of the rays”. In fact, this challenge has found no answer in more recent scientific exploration. No experimental explosion at any scale has ever produced anything comparable to the well-defined 1500-kilometer “rays” of Tycho.

Even more telling is the fact that the rays are punctuated with numerous small craters. An early explanation was that "some solid material was shot out with the jets and produced 'on-the-way' craters". But such narrow trajectories for secondary impactors are an absurdity under the mechanics of an explosion. And the total volume of ejected material needed to form the secondary craters along Tycho's rays, would amount to some 10,000 cubic kilometers – an amount of material entirely inconsistent with careful measurements indicating that practically all material excavated from Tycho's crater has been deposited in its rim. However, the ray elements, terminating on small craters, are the very markers that today’s electrical theorists have cited repeatedly as definitive evidence of an electrical discharge path. As Wallace Thornhill has so often observed, such discharge streamers frequently terminate at a crater. In fact, this is exactly what Gene Shoemaker found when investigating the puzzles of Tycho—"...many small secondary craters, too small to be resolved by telescopes on earth, occur at the near end of each ray element."

When compared to an imagined sphere of the Moon’s average radius, the surrounding highland region occupied by Tycho is more than 1200 meters above the “surface” of that sphere. The crater site appears to be at the summit, or very close to the summit, of terrain that trends downward in every direction away from the site for hundreds of kilometers. For the impact theory, this location can only be an accident. But for the electrical theorists, the elevation on which Tycho sits is not accidental. Lightning is attracted to the highest point on a surface. (That is, of course, the principle behind lightning arrestors placed on the pinnacles of tall buildings).

Though astronomers see Tycho’s rays as material ejected from the focal point of an impact, a mere glance at the picture above is sufficient to make clear that not all of the streamers radiate from a central point. Is this surprising? A mechanical impact has a single focal point and cannot explainthese offset rays. Juergens noted that they "diverge from a common point, or common focus, located on or buried beneath the western rim of the crater." The electrical interpretation of Tycho sees the streamers as paths of electrons rushing across the lunar highlands to the highest point, where it launches into space to form the lightning "leader" stroke. The high point is destroyed in the process. The powerful lightning "return stroke" that forms the Tycho crater comes minutes afterwards and focuses on the nearest high point, a few kilometers to the east. In support of this explanation, the crater Tycho is surrounded by a dark halo of ejecta that blankets the extensive ray system, laid down earlier.

Tycho's crater rim rises about one kilometer above the surrounding terrain and the crater walls exhibit terraces (shown here) that are not characteristic of high energy explosions. However, such terracing isobserved in innumerable instances of electrical discharge machining. (See the large terraced crater in the picture on the right here). This terracing may be due to the fact that electrical current flows in plasma in the form of twisted filament pairs – rather like a double helix. So the terracing is caused by the cutting action of the rotating current filaments on the crater wall. Indeed, some lunar craters exhibit bilateral corkscrew terracing – another observation inexplicable by the impact model, but remarkably consistent with the principle of an arc constituted of twin rotating “Birkeland Currents”.

While it is possible to get a “rebound peak” close to the center of an explosion, such a peak is not typical. In the electrical cratering experiments by plasma physicist CJ Ransom, (as seen here) central peaks were often the norm. As long ago as 1965, attention was drawn to the similar incidence of craters with central peaks in lunar craters and laboratory spark-machined craters. They seem to be an effect of the rotating current filaments, which may leave the center of a crater relatively untouched.

The electrical theorists find great irony in the many examples of earlier researchers who pointed to the electrical properties of phenomena that official science eventually learned to ignore. In 1903, W. H. Pickering, in his book The Moon, suggested that electrical effects could account for the narrow paths of Tycho’s “rays”, and he drew a direct comparison to the streamers seen in auroral displays. But as occurred so frequently in the twentieth century, evidence of electrical activity in space was ignored because it found no place in gravitational cosmology or in the curricula of astronomers and geologists.

NEXT: Lunar Craters—a Failed Theory (2)

The Puzzles of Aristarchus

Credit: NASA

Two prominent craters on the Moon appear in this photograph taken from orbit during the Apollo 15

mission. The large bright crater toward the center is Aristarchus. On the right is the crater

Herodotus, from which extends the great rille of Schroeter’s Valley (a subject of the next article

in this series).

Mar 10, 2006

Lunar Craters—a Failed Theory (2)

The Puzzles of AristarchusThe crater Aristarchus, pictured above, stands out in all Earth-based telescopic images of the Moon. Of the larger formations on the Moon, this rayed crater is considered the brightest. It is also distinguished from its surroundings by its elevation on a rocky plateau rising more than 2 kilometers above the dark “mare” of Oceanus Procellarum. For context, we have circled the Aristarchus scar on the Hubble image (large) placed here.

In the Hubble image we see the crater Tycho, a subject of our previous submission, dominating the southern face of the Moon. Well to the north of Tycho is the second most dramatic feature of the Moon, the impressive spidery scar of Aristarchus, covering a much greater area than one might suspect from close-up images of the crater itself. For further context, a darker image we have placed here shows the relationship of the crater itself to the extended filamentary “rays”.

As can be seen most clearly in the Hubble image, the rays or streamers do not all radiate directly from the crater, and they are not linear. These two facts, undeniable on direct observation, make clear that the streamers are not ejecta. Additionally, the close-up images of the crater (as in our picture above) show that many if not all the “rays” are not deposits of ejecta but depressed channels, as if material has been removed from the bright paths by the very event that produced the crater.

Yet strangely, the idea of ejecta from Aristarchus remains the standard explanation. An artificial convergence of scientific opinion has enabled theorists to look past essential and obvious details that challenge the established perspective.

It can be disconcerting to realize that things either ignored or forgotten by astronomers and planetary scientists include countless pointers to a new and far more unified foundation for planetary science. In fact, evidence of past electrical events on the Moon was noted very early in the twentieth century. (See “”Lunar Craters—A Failed Theory”)

More than forty years ago the British journal Spaceflight published the laboratory experiments of Brian J. Ford, an amateur astronomer who suggested that most of the craters on the moon were carved by cosmic electrical discharge. (Spaceflight 7, January, 1965).

In the cited experiments Ford used a spark-machining apparatus to reproduce in miniature some of the most puzzling lunar features, including craters with central peaks, small craters preferentially perched on the high rims of larger craters, and craters strung out in long chains. He also observed that the ratio of large to small craters on the Moon matched the ratio seen in electrical arcing.

In 1969, just prior to the first Moon landing, Immanuel Velikovsky suggested that rayed craters on the Moon were the result of electric arcs—cosmic thunderbolts. Since terrestrial lightning can magnetize surrounding rock, Velikovsky predicted that lunar rocks would be found to contain remanent magnetism. Astronomers saw no reason to consider such possibilities, and they were caught by surprise when lunar rocks returned by Apollo missions revealed remanent magnetism.

In 1974 the engineer Ralph Juergens published two groundbreaking articles arguing that major features of both the Moon and Mars were electrical discharge scars. Juergens drew attention to both Tycho and Aristarchus on the Moon, suggesting that these features display the unique attributes of cosmic thunderbolts. First, there are the long linear streamers that mark the paths of electrons rushing across the surface toward a regional high point. This is the event that provokes the leader stroke of a discharge. Then, the explosive discharge from a more intense return stroke excavates a crater surrounded by an electrical discharge effect called a “Lichtenberg figure”, a pattern well known in industrial applications of electric discharge.

To illustrate the point, we’ve placed a picture here showing the effect of a lightning stroke on a golf course. The resulting Lichtenberg figure displays a typical “dendritic” pattern (as in the branching of a tree or a drainage system). From the circumference of the figure any filamentary “dendritic” path can be followed back to the discharge point.

On the Moon, in the case of Tycho, Aristarchus, and numerous lesser instances as well, we see Lichtenberg figures superimposed upon the longer linear rays tracing the electron paths that preceded a cosmic discharge. The long linear paths are often slightly “displaced”: In electrical terms they would not be expected to stand in a strictly radial relationship to the focal point of the subsequent discharge.

But the paradoxes of scientific perception abound. On the Moon, the Lichtenberg pattern is supposed to mark the trails of debris from an impact explosion. But we see similar Lichtenberg patterns elsewhere in the solar system, and in these cases the accepted “explanations” take us in opposite directions. The entire equatorial region of Venus is covered with effusive Lichtenberg figures, as can be seen in the pictures here and here. These extraordinary patterns are claimed to signify flowing lava—though for this interpretation to hold one has to believe that the familiar dendritic “drainage” was reversed, with the branching occurring downstream: Lichtenberg figures do not make good drainage patterns from the center outward!

Lichtenberg patterns are also present on Saturn’s moon Titan. Here they are said to be “drainage channels” for liquid methane, though we have challenged that interpretation in a previous Picture of the Day. (The connection between the patterns on Titan and Venus was also the subject of an earlier Picture of the Day, “Titan’s Big Sister”).

The value of the Lichtenberg figure is that it is easily and definitively distinguished from the radial pattern of exploding ejecta. Ejecta follow neither fine linear nor dendritic paths. But electrical arcs do, and that is the nature of the most prominent “blast” patterns on the Moon. Look at the Hubble picture again to see if the longer, slightly displaced radial paths, together with superimposed Lichtenberg patterns, are in fact the case. Once discerned, the truth of the matter is impossible to miss.

NEXT IN THIS SERIES — March 14: Lunar Rilles