written and copyrighted by Týra Alrune Sahsnotasvriunt, June 2014

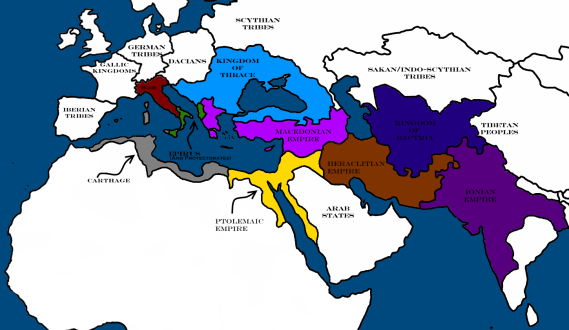

Due to the lack of written records little is known about the Thracians (~2000 BC – ~375 AC) who settled in nowadays’ Bulgaria, Turkey and Romania).

Information may be scarce, but also there are no two sources that will agree upon who and what the Thracians were exactly, how they lived and worshipped. They were mentioned in the Ilias and Odyssee, by philosophers like Herodot and described as hard-drinking and rough-necked, which paint them as some sort of bon sauvage.

Since Roman and Greek philosophers’ accounts of history and other cultures are best taken with a grain of salt it is unclear whether these depictions of them are somewhat correct or rather misinterpretations of the actual Thracian culture(s). Greek and Scythian sources mainly speak of them as people dedicated to art, “just war”/justice and courage.

Amongst reconstructionists the debate whether their forefathers’ spirituality was a monotheistic, monistic, partly pantheistic or simply polytheistic one has been avidly discussed on various online forums.

Some of the confusion might stem from Herodot’s accounts of the Thracian people. He writes, “These Thracians, when there’s thunder and lightning, shoot arrows towards the sky, threatening the god, because they think there is no other god than theirs.”

The Thracians were one of the oldest and largest indo-Germanic people, consisting of about 90 tribes which yet were never unified. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ancient_tribes_in_Thrace_and_Dacia Each tribe/community was led by a high priest often called priest-king, basically a shaman.

Even within the Thracian spirituality different tribes worshipped and acknowledged different Gods or adopted foreign tribes’ Gods who lived in close proximity to them. (>Greek Hestia, Zeus etc. part of several Thracian pantheons.)

Now, whilst this is a common Pagan phenomenon, it is not exactly comparable to Germanic Paganism for example, where the same Germanic Gods were known under different names, depending upon the tribe, yet rituals and religious conduct were the same or at least very similar to each other. Thracian spirituality and culture was geographically specific and there were only marginal overlaps. This is one reason it is so hard to paint a complete and reliable picture on “THE Thracian belief” – there simply was no such thing.

The creation myth of the Thracians (southern Carpathians) speaks of an impenetrable darkness and its ocean from which a God emerged. First, there were a worm and a butterfly both floating on the ocean. The butterfly, madly and desperately batting its wings, rose from the ocean, whilst the worm remained ‘trapped’. When the butterfly was first transfigured into a handsome young man and shortly after into a God, the worm became a kind of ‘devil’.

This further illustrates the Thracian belief of a life of struggle (for perseverance, self-sufficiency and justice) even further. From the butterfly mankind descends, and once they “fall”, sin, do evil etc. they “lose their wings” and regress to the “worm state”. Life is all about maintaining their “wings”.

In most creation myths there was a “void” or “chaos” in the beginning – without any mention of any creature or being as in this early Thracian tale though.

This reminds of the Babylonian Enuma-Elish and other Mesopotamian and the Zoroastrian creation myths in which pantheism and monism played a role.

Zoroastrian Ahriman was also a “worm in the dark” and even in the Finnish (Ugric) Pehlevi scriptures, which were influenced by the Persians, the original “evil” entered this world in the form of a worm, a lower being without (common) sense, slave to its animal desires, while the ‘true’ God was depicted as pure light or a winged creature representing light, everything good, pure and free from human boundaries (the body).

Interestingly, the Thracians did not only have contact with the Persians (today’s Iranians) but were ruled by them for a while, which might explain the similarities in creation myth.

Amongst the Thracians were the Getae and Dacians (who resided in the area around today’s Romania and Moldova) with their own distinctive pantheons and culture.

Gebeleizis was one of the main Gods of the indo-Germanic Getae, the God of thunder and lightning, often depicted with a spear, lightning or arch in his hands facing/battling a snake.

It is not only this but also his bushy large beard and bright red hair that remind of another God of thunder – Germanic Thor.

Gebeleizis, also called Derzelas, Derzis or simply “The Thracian Knight” can also be found in Macedonian mythology as well as the Greek one where his name was Zeus. (On a side note, the main God of the Saxons, “Saxnot” aka Týr, Teiwas, Tiw, Ziw was also known under the name Ziu or Zius. Not only by name but his traits did he remind of Zeus).

It is from Gebeleizis that the Armenian Hetanists (Armenian “Heathens”) adopted him around the 7th century BC and gave him the name Vahagn, God of War and the Sun, the “snakeslayer” who was also equated with Zeus.

Traces of him can even still be found in the tale of “St. George” slaying the dragon.

As Gebeleizis name was greconized to Zbelsurdos beliefs of a female alter ego started forming as well. Her name was Bendis, in other traditions she was named Kotys, the Great Mother Goddess, deity of the moon, womanly cycle and the hunt, (>Artemis) often depicted standing between a deer and a snake, representing her role as a deity of balance and the cycle of nature.

The Mother Goddes(ses) were highly revered and worshipped by both men and women. It comes as no surprise that although the cultural roles of men and women were clearly defined, spiritually they had the same rights and freedoms.

Thracian/Phrygian Sabazios, the King (rather: shaman) of the “horsemen” possessed traits of Wotan, especially in his regard to his eight-legged horse Sleipnir and the fact that he was linked to the underworld and realm of the dead. Although Gebeleizis and Zalmoxis are often equated Sabazios and Zalmoxis appear to have more commonalities.

These just as a few random examples on how complex, interwoven and yet distinctive from each other the Thracian Gods within their sub-cultures and traditions were.

One thing that almost all scholarly sources agree upon (and even the cantankerous online folks) is that Zalmoxis/Zamolxis/Salmoxis/Zalmoxe was the high God of the Dacians and (most of) their sub-tribes.

It is unclear whether Zalmoxis was a man, namely a slave of Pythagoras, who then was elevated into “Godhood” or not. We only know that he was and is worshipped as a God, albeit with the connotation “man-God”, which might just as well describe his role as the “God of man(kind), the main god, “All-father figure” et al.)

However, his followers believed that they would join their God in the afterlife for eternal pleasure after a hard-working life striving for justice. To ensure this, they “sent a messenger” to him every four years. – Meaning a human sacrifice.

To be chosen as a sacrifice was considered an honor, now whether the “sacrifices” (victims?) agreed we’ll never know… The sacrifice was chosen by lot and he/she was then immediately cast high into the air and onto 3 sharp spears.

Needless to say the victims did not die instantly in most cases and were visited during their long, painful hours of slow but certain death by family who cheered them on or asked them to deliver messages to Zalmoxis.

In some cases however, the sacrifice did not die. This was considered to be proof that the sacrifice was “unworthy”, that he/she had lived a life in vain, one of evil or sin. (The concept of good and evil was deeply embedded in the Thracian mindset.) Once a sacrifice lived, another one was chosen instantly.

Dacian life revolved around Zalmoxis and the (rewards of) afterlife. It was Herodot who mentioned the similarity of Zalmoxis, the “man who became (a) God”(6 BC) or “daimon” to Pythagoras who is sometimes said to have been his slave-master and/or teacher. The set of religious ideas whose origin is attributed to Zalmoxis does indeed resemble Pythagoreanism. Besides immortality, Zalmoxis is said to have also taughthis followers a highly praised form of psychosomatic medicine based on incantations, magic and charms, whose purpose was to bring healing by unifying the soul with the body. (Plato: Charmides)

This medical tradition appears to have been long-lived, as 40+ Dacian names of medicinal plants were inserted in the famous Materia medica of the Greek physician Dioscurides and in De herbis (3rd century CE).

Today’s Romanian incantations (folklore, “folktro”), rituals of the dead, folk dances like the Hora etc. still bear resemblance of what is known of the Dacian culture(s).

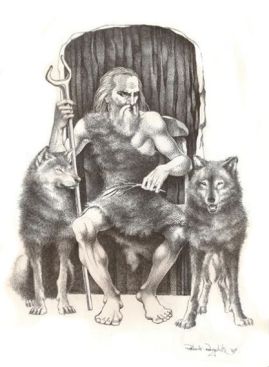

If you visited Romania recently, maybe you took notice on the plenty of bars, pubs, sports clubs or even stores which carried the name “wolf” in them. The word “Dacian” means nothing other than wolf itself (daos=wolf).

They were the wolf people, pack people. In battle, much like the Germanic berserkers frenzied themselves into battle rage, the Dacians would imitate the wolf’s howl and ready themselves for battle. They fought for their “pack”, for justice for their pack. It is surprising that they appear not to have had a Goddess like Germanic Angerboda, wolf/pack mother of Iron Wood.

Another animal sacred to them was the serpent, or more specifically its mythological variant, the dragon. Even today’s Zalmoxianists revere and celebrate the “holy fire” and wolf and dragon adorn many a flag, banner or are found in the logos of neo-Pagan organizations.

In the spirit of “ye olden days” today’s Zalmoxianism is not “one religion” and its followers are not unified. There is an ongoing debate between the various groups on who actually follows the “true” Zalmoxianism. A debate inherited by early 20thcentury historians such as Nicolae Densușianu, Vasile Pârvan, Giurescu, Jean Coman, Constantin Daicoviciu, and Mircea Eliade. Their claims and research material is still as controversial as it is incomplete and often takes a political or (Christian) religious character.

However, it is true that 21st century Zalmoxianism heavily leans on Romanian folklore rather than actual Geto-Dacian or general Thracian spirituality hence.

The ethnologist Ion Ghinoiu states that the Romanian lives in the proximity to the divine and that he personifies stars, creatures (animals, birds, reptiles, insects), plants, natural phenomena, illnesses, sentiments, soul feelings. And indeed most neo-Zalmoxian worship and practices are pantheistic in nature or embed core pantheistic elements in their set of beliefs.

For the early Indo-Europeans, the worship of fire was central to their beliefs as it was pivotal to their survival. (Comp. Armenian Hetanism and Tseghakron – https://paganmeltingpot.wordpress.com/category/armenian-paganism/)

Nowadays, no one sacrifices animals or even humans in Zalmoxian ritual anymore of course, instead their fire worship is of rather meditative nature. Candles or bonfires are lit, sometimes hymns and songs are being sung or a few prayers to Vesta, goddess of fire (not the similarity to the holy book of the Persian Zoroastrians – “Avesta”) are being spoken.

At Zalmoxis’ Temple in Detunata, Romania, followers gather annually to celebrate the revival of their ancient Gods together. During this ritual celebration of the “fire of creation” the deceased are being asked to reincarnate and spirits are being called upon to manifest.

But even here rituals are not entirely free from Christianity. Alongside the 6-petaled flower the Christian (Celtic) cross is bowed to, it is placed in the center of the altar, those Zalmoxians believing in “Dumnezeu” (The Lord of Lords, also the Romanian name for the Christian God) even call upon Jesus. Undeniably this is a kind of eclecticism that doesn’t make much sense anymore in terms of a fulfilling or somewhat traditional (logical?) spirituality. To each their own of course.

In 2010 the attempt of writing the “Book of Zalmoxis”, basically a Romanian Bible, was initiated. It contained the collected interpretations of historians, philosophers, poets like Mihai Eminescu and even scientists. The blanks were filled in with other related indo-Aryan beliefs, mixed in with tidbits of Christianity. The symbol chosen for this Romanian Bible was declared as the new symbol of all of “Zalmoxiana” – Zalmoxis’ cross. (Astonishing enough since there is no mention of a cross in connection with the God Zalmoxis anywhere in historic documents…) It is an equal four-arm cross displaying The Flower of Life symbol, reminding of the original (non-political) swastika (Hindu/indo-Aryan symbol of good luck and life).

Other modern symbols regarded as sacred are the square (symbol of masculinity and linearity), the crescent moon (Bendis/Kotys), triangle (Bendis/Kotys), Hexagon (unification of male and female principle), circle (of life).

The book claims to state historic facts, yet it is at best mainly a curiously eclectic and speculative work. Zalmoxian babies are baptized in the name of Zalmoxis, polyamory and(spiritual) polygamy are the new hit (…) and although there is no mention of it in any historical records why not throw in some sex rites and orgies in the mix, too.

Zalmoxians celebrate the usual Pagan holidays (wheel of the year) along with a few other more Romania-specific, semi-political ones. A few traditions still stem from Roman times or the Gothic occupation.

As is often the case the organized reconstruction of ancient Pagan religions, complete with a “Bible” to go along with it, it doesn’t work. It is in fact against the core of common (ancient) Pagan spirituality, which was mostly un-dogmatic, adoptive and free-spirited, relying on ideas rather than set rules, “commands” and regulations.

There are several Pagan movements out there today whose political extremism (both left- and right-winged), religious intolerance, Christianized mindset, sexual deviance and confused eclectic rituals have turned them into one big embarrassing mess after all.

Anyhow, the largest reconstructionist Zalmoxian groups in Romania are the “Societatea Gebeleizis” (Society of Gebeleizis) with approx. 500 members split into 15 branches. Due to their core values and motto of the Societatea, “O Familie, Un Neam, Un Teritoriu” (One Family, One Nation, One Territory), left-wing extremists have accused the society of being nazist. There are rumors of scandals within the organization, however I personally haven’t found any concrete proof regarding these alleged “scandals” nor their nature. (Should anyone have information on this please do contact me though and I shall revise this entry.)

Other well known groups are Zalmoxe and Terra Dacica Aeterna as well as several smaller and lesser known ones.