Images: Kayenta & squatter petros

Mar 02, 2007

Plasma in the Lab and in Rock ArtThe ancients were not just doodling when they spent millions of man-hours carving rock art forms around the world. They were reproducing dramatic plasma discharge forms seen in their spectacular sky.

At high energy levels, the current within a plasma circuit will develop instabilities that can be studied in the laboratory. The flow of charged particles generates electromagnetic forces that in turn affect the flow of particles. This feedback effect produces plasma behavior that is not linear and is often unexpected. Theoretical predictions must be frequently checked against laboratory observations. The non-linear behavior at low energies, such as the alternating light and dark segments in a gas-discharge tube, becomes even more complex. High energy discharges in plasma laboratories exhibit intricate structures, and these evolve through a sequence of quasi-stable forms with intermediate stages of violent transformation.

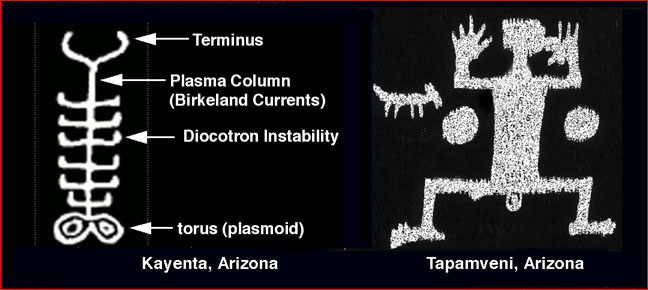

Anthony Peratt, a researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory, has studied the evolution of these instabilities for several decades. One evolutionary sequence is the development of the “warped disk” form, which can involve many variations on the underlying pattern. (See Thunderbolts of the Gods, Chapter One, pages 21ff.) A continuous discharge channel will break up into a string of spherical cells, usually 7 to 9 in number. These cells contract further into toroids (donut-shaped rings) stacked along the axial channel. The toroids flatten into disks, and then the edges of the disks warp upward or downward. When viewed from the side (perpendicular to the axis), the greater thickness of plasma along the axis and in the plane of the disks appears as a glowing line figure—a vertical line with cross bars.

Peratt described this sequence at an interdisciplinary conference on plasma in the solar system in September of 2000. David Talbott, another presenter at the conference, remarked on the similarity of the line form to images seen in ancient rock art. The pictograph on the left above, from Kayenta, Arizona, illustrates a late stage in this sequence. Peratt remarked that the detailed correspondence with the laboratory discharge sequence is precise. This Kayenta image was, in fact, the first pictograph that Talbott sent to Peratt, and it inspired Peratt to investigate the correspondence further. (The identification of the discharge components comes from Peratt’s later paper on the subject. According to Peratt, the configuration is about to undergo an intensely energetic transformation that could be deadly for humans exposed to its radiation.)

In the transitional phase, the top disks fold over each other to form a bulb shape; the next disk bends into a cup shape; the middle disks often merge; and the lower disk bends down into the shape of an inverted cup. The bottom of the axial current often develops a trident shape. When viewed from the side, the line figure takes on the appearance of a squatting stick person with his arms in the air. The central toroid appears as two dots or, if bright enough, as a bar under the “stick man’s” arms. The trifurcated bottom end of the axial current is commonly interpreted in rock-art lore as the “stick man’s” genitalia. Peratt calls this a “basic” form taken by discharge instabilities, and significantly it is an image common to rock art around the world. (See image on the right.)

Peratt’s investigation of rock art led him to collect hundreds of thousands of digital photographs of petroglyphs (images scratched or pecked into rock) and pictographs (images painted on rock). He has classified them into 84 categories that correspond with the quasi-stable forms of the laboratory plasma discharges.

“Many petroglyphs, apparently recorded several millennia ago, have a plasma discharge or instability counterpart, some on a one-to-one or overlay basis. More striking is that the images recorded on rock are the only images found in extreme energy density experiments; no other morphology types or patterns are observed,” Peratt writes, “The inward rise on axis along with the upward folding of the outer edges of the carved lines and transition to edge curling, a phenomena [sic] recorded in intense electrical discharge radiographs, could not have been known to prehistoric man unless he witnessed the same event in the sky.”

Peratt and his assistants and collaborators also recorded the fields of view of the ancient artists and the locations of the images with GPS instruments. By plotting this data on computerized topographical maps, he can calculate where the various forms occurred in the Earth’s ancient plasmasphere (what astronomers call the magnetosphere).

Peratt surmised that a surge of power in the currents driving the auroras had set off the sequence of instabilities. The entire pre-historical sky around the globe would have appeared to come alive with a shimmering, shining “enhanced aurora” that stretched from pole to pole. It would have featured exactly those abstract figures and stick men and strange animal-like shapes that appear only in rock art and in high-energy plasma discharges. He contends that the ancient artists were witnesses to this “enhanced aurora” and that they recorded what they saw on the most durable “recording device” available—rock surfaces.

From the difference in scale between a laboratory spark and an auroral discharge, Peratt estimates that the ancient displays would have lasted “for at least a few centuries if not millennia.” Radiocarbon dating of material overlying some buried petroglyphs provides a time for the occurrence of the displays at 4 000 to 12 000 years ago.

The curious phenomena that our space-age sensors are detecting in space, phenomena that can be explained directly in terms of the electrical behavior of plasma, are now reflected in the forms of ancient rock art. The new universe of plasma requires not only a new vision of the present but also a new vision of the ancient past. Discoveries in space, ancient drawings of the sky, and controlled laboratory experiments converge to revolutionize our understanding of the cosmos. Plasma and electricity make possible a unified perspective, a goal that is fundamental to the scientific quest.