Excerpts From The Electric Universe

Part 6

The following is one of a series of excerpts from The Electric Universe, copyright © 2002, 2007 Wallace Thornhill and David Talbott and published by Mikamar Publishing. Reproduced with the kind permission of the authors and publisher.

Presented by Dave Smith |

| |

| April 25, 2010 |

| |

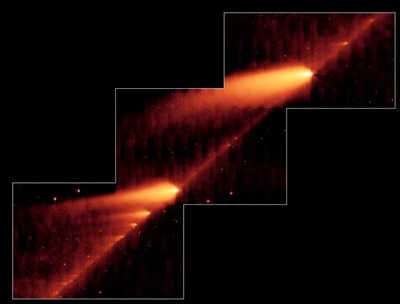

| When Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 fragmented in 1992 upon a close approach to Jupiter, it gave us indications that its changing electrical environment was responsible for the breakup, as orthodox theories failed miserably with a comet so far from the Sun. When the fragments returned to collide with Jupiter in 1994 it gave us unprecedented opportunity to evaluate the validity of the models on offer.

Page 108

Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

The famous collisions of fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 (SL-9) with Jupiter provide a spectacular confirmation that comets have a store of energy in addition to their kinetic energy. On 7 July 1992, SL-9 grazed past the giant planet Jupiter a mere 20,000 km above the cloud tops. It had penetrated deep into Jupiter's huge plasma sheath. As it switched suddenly from the Sun's electrical environment to that of Jupiter, it would have experienced extraordinary internal electrical stress. Unsurprisingly, it broke up. In fact, after the main disruption event some of the fragments split further in the rapidly changing electrical environment. It is this tendency to fragment, when gravitational and rotational forces are far too weak to explain it, that gives rise to the idea expressed by some astronomers that comets are a pile of fragments.

The fragments of SL-9 returned to collide with Jupiter during the week of 16–22 July 1994. Some astronomers predicted that the fragments were too small to have much effect. “There's a chance we will see very little,” hedged Eugene Shoemaker, late of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and co-discoverer of the comet, shortly before the event. Since SL-9 had done nothing to distinguish itself before it broke up— it couldn't be found in images taken before the break-up—astronomer Brian Marsden surmised that it was 1 to 2 kilometers in diameter. “It's

Page 109

going to be tough to see much,” he concluded. “I don't think there's going to be a very large explosion.” But planetary physicist Jay Melosh summed up the uncertainty, “Theoreticians are often wrong, especially in predicting things.” 117As we know, the spectacle exceeded all expectations. But were the collisions simply impacts in a purely mechanical sense—or did the electric charge of the comet fragments contribute significantly to the event?

|

| |

(from Page 108)

[Click to enlarge]

|

| |

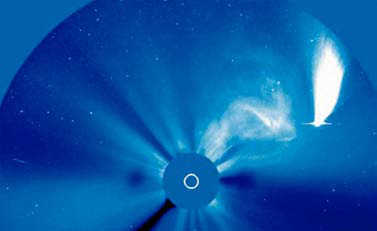

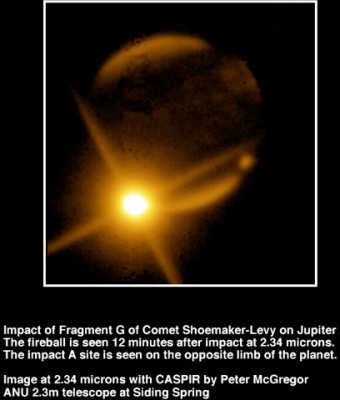

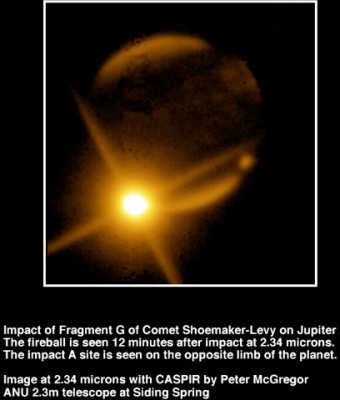

Initially, the dazzling display baffled astronomers because there were remarkable electrical phenomena. Renée Prange of the French Institute Astrophysique Spatiale, a member of the Hubble upper atmosphere imaging team, saw 'northern lights.' Ultraviolet images showed glowing streaks in Jupiter's northern hemisphere which appeared as almost mirror images of glows from the impact site of fragment 'G' in the southern hemisphere. According to Dr. Prange, the northern glows appeared farther south than ever before: “I think it's a major discovery.” The Jovian auroral displays appeared to be triggered by electrically charged particles released during the impacts in the south following a looping arc northward along the planet's magnetic field until they fell back into the planet's atmosphere, creating a glow in the north. According to Dr. Prange, it is still unclear whether the particles were comet dust that became electrically charged as it fell through the planet's magnetic field or gas molecules from the planet that became charged in the heat of the fragment's impact and explosion.118

Then, after a year's analysis “by hundreds of talented scientists,” Nature119issued a consensus report: “First seen was a faint glow that slowly increased in brightness on a time-scale of tens of seconds, believed to be due to a large number of small meteors in the coma surrounding each SL-9 fragment. The meteor shower was followed by a sharp increase in brightness as the main part of the fragment entered the Jovian atmosphere…. A few tens of seconds later, a fireball exploded up the 'chimney' created in the atmosphere by the bolide.”

The explanation for the initial glow, coming after the fact, only served to confirm the power of ideology in comet science. In electrical terms, the charged comet fragments would be expected to exhibit a glowing coma as they approached Jupiter. The glow would increase until a sudden arc discharge would occur between Jupiter and the comet fragment. The steep increase in brightness that astronomers observed has more in common with a lightning flash than the lightcurve of a bright bolide's entry into the Earth's atmosphere. In fact, it

Page 110

was expected that the fragments would flare several times like fireballs that enter the Earth's atmosphere.120 That didn't happen.

As we shall see, there is no evidence that the fragments entered the atmosphere. That and the fireball exploding up a 'chimney' are simply presuppositions of the impact model. And there were many other anomalies for the impact model.

In Jupiter's plasma environment, we can expect electrical forces to affect the trajectories of the charged comet fragments. Such forces would cause deviations from expected impact times. And in fact impact times were on average 8 minutes later than expected.121

One of the largest pieces, fragment G, showed spectral evidence of magnesium when it was just 10 hours from impact. Such metals only show up when comets graze around the Sun. But whatever was tearing magnesium from the fragment as it sped in through Jupiter's magnetosphere couldn't drive off enough water to be detectable. That failure to observe water gave rise to questioning whether the comet might be an asteroid. After all, only the fuzziness of SL-9 identified it as a comet, and some asteroids have been observed occasionally to show fuzziness.122

The electrical comet model explains each and every mystery of SL-9. An electric comet is as dry as an asteroid. The 'fuzziness' of a comet is due to electric currents flowing in its plasma sheath, causing the sheath to glow. When the electrical stress increases beyond a threshold, the plasma in the sheath will establish arcs at the surface, which will machine dust and atoms, such as magnesium, from the minerals there. That this should occur shortly before the collision is not surprising: Jupiter's magnetosphere is the most active electrical environment for a comet outside a close encounter with the Sun.

Dr. Earl Milton, before the above paper was published, wrote, “When comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 meets Jupiter, spectral changes in the comet's tails might become conspicuous once the comet leaves the solar wind and enters Jupiter's electrosphere [magnetosphere or plasma sheath]. This part of the encounter precedes by hours the meeting of the nuclei with Jupiter's atmosphere.”123 Here we see the contrast between an old hypothesis that should be discarded and a better one. The electric comet hypothesis has explanatory and predictive power.

The Galileo spacecraft on its way to Jupiter, the Hubble Space Telescope, and many terrestrial observatories tracked the fragments as

Page 111

they approached Jupiter. Their data highlighted another mystery. Some collisions that were calculated to occur just beyond Jupiter's limb and that should have been invisible to all but the Galileo spacecraft were seen from the Earth. In a NASA news report,124 Dr. Andrew Ingersoll said, “In effect we are apparently seeing something we didn't think we had any right to see.” “It seems clear that something was happening high enough to be seen beyond the curve of the planet,” said Dr. Torrence V. Johnson of JPL. The predictable electrical event prior to the fragment striking Jupiter's upper atmosphere, did indeed occur.

Chemical analyses threw up more mysteries. Sulphur, ammonia, carbon disulphide and glowing acetylene and methane heated by the collisions were found—but no water or even an oxygen-bearing molecule. This is a problem because the current theory of Jupiter's structure requires a layer of water clouds below the top clouds of ammonia. Present theories of the formation of the Solar System require that both Jupiter and comets have water—yet no one found signs of any water at all.

According to Dr. Lucy McFadden of the University of Maryland, “It is disturbing. This means either that our modeling is not correct, or the comet exploded before it reached Jupiter's water layers.” But SL-9 was originally classified as a comet because its fragments each appeared to have a 'coma,' assumed to be a halo of water vapor, dust and gas.125 An explosion above the hypothetical water layers of Jupiter would still not explain why none of the comet's own water turned up. That leaves only the first half of McFadden's either-or: “our modeling is not correct.”

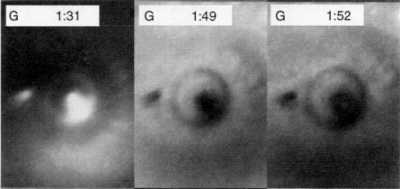

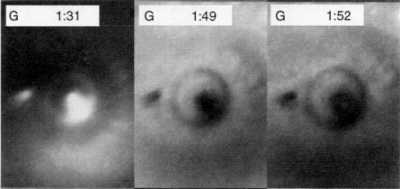

What, then, were the vertical jets seen rising three thousand kilometers above Jupiter's atmosphere and known as 'plumes?' And what were the crescent-shaped dark features that resulted from the fallback of the plume onto the atmosphere? The dark material came to be known technically as the 'brown stuff,' its nature unknown ([below]).

|

| |

In this time-sequence image of SL-9 fragment G's collision with Jupiter. The number is the time from impact in hours. Note the strange 'rays.' The wavelengths recorded from left to right are 889 nm [infrared], 555 nm [visible], and 336 nm [ultraviolet]. The infrared image (LEFT) shows the dark material to be warm (bright). North is up; Jovian west longitude increases to the left.

Image Credit: NASA-ESA Hubble Space Telescope, STScI.

Credit: H. B. Hammel et al., HST Imaging of Atmospheric Phenomena

Created by the Impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9,

Science, Vol. 267, 3 March 1995, p. 1289.

[Click to enlarge]

|

| |

Melosh suggested that the comet fragments would penetrate Jupiter's atmosphere so deeply before exploding that they would be swallowed up and we would see very little. Others proposed that each fragment would dig a 'tunnel of fire' in Jupiter's atmosphere before exploding and sending a plume of hot atmospheric and cometary material from the top of the tunnel into space. This was the 'plume' model that was explored to try to explain the strange dark fallout pattern.

Page 112

However, the plume model could not explain the clear zone between the dark core and the crescent. Nor could it explain the radial lines dissecting the crescent.

Ironically, the answers to the puzzles come from Jupiter's closest moon, Io. In November 1979, the noted astrophysicist Thomas Gold proposed that the gigantic plumes on Io are not volcanic but evidence of electrical discharging.126Years later, a paper by Peratt and Alex Dessler followed up Gold's suggestion, showing that the discharges took the form of a 'plasma gun effect,' which produces a parabolic plume profile, filamentation of the matter within the plume, and the termination of the plume onto a thin annular ring.127 These are precisely the effects seen in the encounter of SL-9 with Jupiter.

|

| |

A so-called 'volcano' on Io shows the typical penumbral fallout ring of a plasma gun. It is a precise analog of the fallout rings on Jupiter generated by plasma arcs between Jupiter's ionosphere and the comet fragments.

Image credit: JPL & NASA

[Click to enlarge]

|

| |

All of the unexplained oddities begin to make sense, if a plasma discharge occurred between the highly charged comet fragments and Jupiter's ionosphere. The electromagnetic pinch of the plasma gun effect preferentially heats ions to temperatures far hotter than the Sun and produces the bright, lightning-like flash and subsequent glow. That is why the light from fragments that were expected to impact beyond the limb was unexpectedly visible. The light from a discharge at 3,000 km above Jupiter's cloud tops would have been visible from Earth. The electrical nature of the event will also explain why comet fragments of differentsizes created fireballs of the same height.128 The discharges occurred as different fragments penetrated the same 'double layer' of Jupiter's plasma sheath.

A plasma discharge would also explain why the expected compounds, such as water, from deeper cloud layers were not seen in the plumes. The comet fragment is vaporized and ionized by the energy of the discharge. Constrained by powerful electromagnetic forces, the silicate particles and other ionized compounds from the rocky comet form the warm plume and crescent-shaped fallout pattern of 'brown stuff.'

What was the 'brown stuff?' The Hubble Space Telescope found “most surprising were the strong signatures from sulfur-bearing compounds like diatomic sulfur (S2)...”129 However, S2 is a molecule with a very short lifetime and its origin is unknown. “The origin of sulfur in ..comets remains enigmatic.”130 If we return to Io, we find that the 'plasma gun' effect there has covered the moon with colorful

Page 113

sulfur molecules, including red and brown variants. A large quantity of oxygen was observed in the SL-9 events at Jupiter. So it seems likely that the sulfur was formed by fusing two oxygen atoms together in the powerful plasma discharges to form one sulfur atom. Originally, Io was probably an icy moon like its Galilean siblings.

There was no water from the comet, and Jupiter's deeper cloud layers, if they did contain water, were not pulled into the plume. Jupiter's magnetic field is probably responsible for most of the rotation, asymmetry, and offset of the plasma gun discharge pattern.

It may be that children listening on their school's radio telescope provided the most significant observation of all: they said that the SL-9 collisions were accompanied by bursts of radio emissions “just like those from sunspot activity on the sun.”131

The New Scientist called this “Jupiter's surprise radio broadcast.”132Astronomers had expected radio emissions at high frequencies to diminish and to hear the comet crash clearly at low frequencies. Instead, nothing happened at low frequencies while emissions around 2–3 gigahertz rose by 20 to 30%. “Never in 23 years of Jupiter observations have we seen such a rapid and intense increase in radio emission,” said Michael Klein of JPL. The radio emission peaked on 23 July, just after the last comet fragment hit, and it declined thereafter. Klein had expected dust from the comet to absorb electrons, which otherwise might contribute to radio emissions. “Instead, extra electrons were supplied by a source which, as yet, is a mystery.” But it is no mystery. Like all comets, SL-9 was negatively charged, its fragments supplying copious electrons for the radio emissions.

The fate of SL-9 thus provides a consistent picture of the electric comet. The picture includes the original break-up and and subsequent further fragmentation of the comet, plus the surprising events that occurred in the 1994 impact with Jupiter: the bright plumes above the Jovian atmosphere; the sightings of 'impossibly' energetic events from Earth; the associated Jovian auroral displays; the absence of water in the vaporized debris; and the lack of the expected constituents from Jupiter's atmosphere, all pointing to the termination of each fragment's flight in spectacular flashes before it entered Jupiter's atmosphere.

|

| |

The famous 'string of pearls' of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 fragments before impact.

Credit: NASA, Hubble Space Telescope (courtesy of H. Weaver)

[Click to enlarge]

|

| |

References:

117 R. A. Kerr, Science, Vol. 265, 1 July 1994, pp. 31-2.

118 The Baltimore Sun, 21 July 1994, p. 12A.

119 P. J. T. Leonard, “Impact consensus emerges,” Nature, Vol. 375, 1 June 1995, p. 358.

120 Z. Sekanina, “Disintegration Phenomena Expected During Collision of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter,” Science Vol. 262, 15 October 1993, pp. 382-3.

121 H. B. Hammel et al, “HST Imaging of Atmospheric Phenomena Created by the Impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9,” Science, Vol. 267, 3 March 1995, p. 1288.

122 Science, Vol. 265, 19 August 1994, p. 1030.

123 E. R. Milton, private correspondence, 24 July 1994.

124 www.jpl.nasa.gov/releases/94/release_1994_9465.html

125 Baltimore Evening Sun, 20 July 1994, p. 9A.

126 T. Gold, “Electrical Origin of the Outbursts on Io,” Science, Vol. 206, 30 November 1979, pp. 1071-3.

127 A. L. Peratt, A. J. Dessler, “Filamentation of Volcanic Plumes on the Jovian Satellite Io,”Astrophysics and Space Science 144 (1988) pp. 451-61.

128 Sky & Telescope News, “Astronomers discuss Comet Crash,” November 4, 1994.

129 NASA News Release 94-161, “Hubble Observations Shed New Light on Jupiter Collision,” p. 3.2.

130 J. Crovisier & T. Encrenaz, Comet Science, p. 49.

131 BBC Radio 4 Science Now, 19 July 1994.

132 New Scientist, 20th August 1994, p. 17.

|