Rough Notes:

Sky deity

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Jupiter, the sky father of Roman religion and mythology

The sky often has important religious significance. Many religions, both polytheistic and monotheistic, have deities associated with the sky.

The daylit sky deities are typically distinct from the night-time sky (or “heaven of the stars”) deities. Stith Thompson‘s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature reflects this by separating the category of “Sky-god” (A210) from that of “Star-god” (A250).

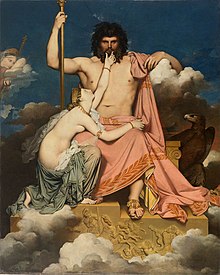

Daytime-gods and Nighttime-gods may also be deities of an “upper world“[disambiguation needed] (or “celestial world”), opposed to a “netherworld” (or “chthonic realm”) ruled by other gods (for example, Sky-gods Zeus and Hera rule the celestial realm in ancient Greece, while the chthonic realm is ruled by Hades and Persephone), or of an upper world and netherworld respectively.

Any masculine sky god is often also king of the gods, taking the position of patriarch within a pantheon. Such king gods are collectively categorised as “Sky father” deities, with a polarity between sky and earth often being expressed by pairing a “Sky father” god with an “Earth mother” goddess (pairings of a Sky mother with an Earth father are less frequent). A main sky goddess is often the “queen” (“of heaven“, for example).

Gods may rule the sky as a pair (for example, ancient Semitic [supreme] god El and the sky goddess Asherah whom he was most likely paired with).[1]

Sky father

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

In comparative mythology, sky father is a term for a recurring concept of a sky god who is addressed as a “father”, often the father of a pantheon. The concept of “sky father” may also be taken to include Sun gods with similar characteristics. The concept is complementary to an “earth mother“.

“Sky Father” is a direct translation of the Vedic Dyaus Pita, etymologically descended from the same Proto-Indo-European deity name as the Greek Zeus Pater and Roman Jupiter, all of which are reflexes of the same Proto-Indo-European deity’s name, *Dyēus Ph₂tḗr.[1] While there are numerous parallels adduced from outside of Indo-European mythology, the concept is far from universal (e.g. Egyptian mythology has a “Heavenly Mother“).

Contents

[hide]

In historical mythology[edit]

- In Mesopotamian mythology, An or Anu, (AN, ???) Sumerian for “heaven, sky”, is the father deity of the Sumerian and Assyro-Babylonian pantheon and is also the earliest attested Sky Father deity.

- Indo-European mythology

- In the early Vedic pantheon, Dyaus Pita “Sky Father” appears already in a marginal position, but in comparative mythology is often reconstructed as having stood alongside Prithvi Mata “Earth Mother” in prehistoric times.

- In Ancient Rome, the sky father, or sky god, was Jupiter (Zeus, Ζεύς, in Ancient Greece), often depicted by birds, usually the eagle or hawk, and clouds or other sky phenomena. Nicknames included “Sky God” and “Cloud Gatherer”. While many attribute a sky god to the sun, Jupiter ruled mainly over the clouds and the heavens, while Apollo is referred to as the god of the sun. Apollo was, however, the son of Jupiter.

- In Māori mythology, Ranginui was the sky father. In this story, the sky father and earth mother Papatūānuku, embraced and had divine children.

- Wākea is a sky father in Hawaiian mythology.

- In Native American mythology and Native American religion, the sky father is a common character in creation myths.[2]

- In China, in Daoism, 天 (tian), meaning sky, is associated with light, the positive, male, etc., whereas 地 (di) meaning earth or land, is associated with dark, the negative, female, etc.

- Shangdi 上帝 (Hanyu Pinyin: shàng dì) (literally “King Above”) was a supreme God worshipped in ancient China. It is also used to refer to the Christian God in the Standard Chinese Union Version of the Bible.

- Zhu, Tian Zhu 主,天主 (lit. “Lord” or “Lord in Heaven”) is translated from the English word, “Lord”, which is a formal title of the Christian God in Mainland China’s Christian churches.

- Tian 天 (lit. “sky” or “heaven”) is used to refer to the sky as well as a personification of it. Whether it possesses sentience in the embodiment of an omnipotent, omniscient being is a difficult question for linguists and philosophers.

- Tengri “sky”, chief god of the early religion of the Turkic and Mongolic peoples.

- In Ancient Egypt, Horus was ruler of the sky. He was shown as a male humanoid with the head of a falcon. It is not uncommon for birds to represent the sky in ancient religions, due to their ability to fly. However, in Egyptian mythology the sky was perceived as the goddess Nut.

- In what is now Colombia, the Muisca (Muisca mythology) used to worship Bochica as the sky father.[3]

- “Taevaisa” (Taevas = sky, isa = father) is the word by which adherents in Estonia of the Maausk (faith of the land) and the Taara native beliefs refer to God. Although both branches of the original Estonian religion – which are largely just different ways of approaching what is in essence the same thing, to the extent that it remains extant – are pantheistic, heaven has a definite and important place in the ancient pre-Christian Estonian belief system. All things are sacred for those of the faith of the land, but the idea of a sky father – among other “sacrednesses” – is something all Estonians are well aware of. In newer history, after the arrival of Christianity, the ideas of a sky father and “a father who art in heaven” have become somewhat conflated. One way or another, the phrase “taevaisa” remains in common use in Estonia.

- The Liber Sancti Iacobi by Aymericus Picaudus tells that the Basques called God Urcia, a word found in compounds for the names of some week days and meteorological phenomena.[4][5] The current usage is Jaungoikoa, that can be interpreted as “the lord of above”. The imperfect grammaticality of the word leads some to conjecture that it is a folk etymology applied to jainkoa, now considered a shorter synonym.

“Nomadic” hypothesis[edit]

In late 19th century opinions on comparative religion, in a line of thinking that begins with Friedrich Engels and J. J. Bachofen, and which received major literary promotion in The Golden Bough by James G. Frazer, it was believed that worship of a sky father was characteristic of nomadic peoples, and that worship of an earth mother similarly characterised farming peoples.

This view was stylized as reflecting not only a conflict of nomadism vs. agriculturalism but of “patriarchy” vs. “matriarchy“, and has blossomed into a late ideological in certain currents of feminist spirituality and feminist archaeologyin the 1970s.[clarification needed]

Reception in modern culture[edit]

The theory about earth goddesses, sky father, and patriarchal invaders was a stirring tale that fired various imaginations. The story was important in literature, and was referred to in various ways by important poets and novelists, including T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce, and most influentially, Robert Graves.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ dyaus in Vedic still retained the meaning “sky”, while the Greek Zeus had become a proper name exclusively.

- Jump up^ Judson, Katherine Berry (April 30, 2009). Myths and Legends of California and the Old Southwest. BiblioLife. pp. 5–7. ISBN 0-559-06288-5.

- Jump up^ Paul Herrmann, Michael Bullock (1954). Conquest by Man. Harper & Brothers. pp. 186. OCLC 41501509.

- Jump up^ Trask, L. The History of Basque (1997) Routledge ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- Jump up^ Jose M. de Barandiaran Mitologia Vasca (1996) Txertoa ISBN 84-7148-117-0

Sacred king

|

|

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducingmore precise citations. (November 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Figure of Christ from the Ghent Altarpiece (1432).

In many historical societies, the position of kingship carries a sacral meaning, that is, it is identical with that of a high priest and of judge. The concept of theocracy is related, although a sacred king need not necessarily rule through his religious authority; rather, the temporal position has a religious significance.

Contents

[hide]

History[edit]

Sir James George Frazer identified – or invented – the concept of the sacred king in his study The Golden Bough (1890–1915), the title of which refers to the myth of the Rex Nemorensis.[1]Frazer gives numerous examples, cited below, and is regarded[by whom?] as an exponent of the myth and ritual school. However, “the myth and ritual, or myth-ritualist, theory” is disputed;[2]many scholars now believe that myth and ritual share common paradigms, but not that one developed from the other.[3]

According to Frazer, the notion has prehistoric roots and occurs worldwide, on Java as in sub-Saharan Africa, with shaman-kings credited with rainmaking and assuring fertility and good fortune. The king might also be designated to suffer and atone for his people, meaning that the sacral king could be the pre-ordained victim in a human sacrifice, either killed at the end of his term in the position, or sacrificed in a time of crisis (e.g. the Blót of Domalde).

The Ashanti flogged a newly-selected king (Ashantehene) before enthroning him.

From the Bronze Age in the Near East, the enthronement and anointment of a monarch is a central religious ritual, reflected in the titles “Messiah” or “Christ“, which became separated from worldly kingship. Thus Sargon of Akkad described himself as “deputy of Ishtar“,[citation needed] just as the modern Catholic Pope takes the role of the “Vicar of Christ“.[4]

Kings are styled as shepherds from earliest times, e.g., the term applied to Sumerian princes such as Lugalbanda in the 3rd millennium BCE. The image of the shepherd combines the themes of leadership and the responsibility to supply food and protection, as well as superiority.

As the mediator between the people and the divine, the sacral king was credited with special wisdom (e.g. Solomon) or vision (e.g. via oneiromancy).

Study[edit]

Study of the concept was introduced by Sir James George Frazer in his influential book The Golden Bough (1890–1915); sacral kingship plays a role in Romanticism and Esotericism (e.g. Julius Evola) and some currents of Neopaganism (Theodism). The school of Pan-Babylonianism derived much of the religion described in the Hebrew Bible from cults of sacral kingship in ancient Babylonia.

The so-called British and Scandinavian cult-historical schools maintained that the king personified a god and stood at the center of the national or tribal religion. The English “myth and ritual school” concentrated on anthropology and folklore, while the Scandinavian “Uppsala school” emphasized Semitological study.

Frazer’s interpretation[edit]

A sacred king, according to the systematic interpretation of mythology developed by Frazer in The Golden Bough (published 1890), was a king who represented a solar deity in a periodically re-enacted fertility rite. Frazer seized upon the notion of a substitute king and made him the keystone of his theory of a universal, pan-European, and indeed worldwide fertility myth, in which a consort for the Goddess was annually replaced. According to Frazer, the sacred king represented the spirit of vegetation, a divine John Barleycorn.[citation needed] He came into being in the spring, reigned during the summer, and ritually died at harvest time, only to be reborn at the winter solstice to wax and rule again. The spirit of vegetation was therefore a “dying and reviving god“. Osiris, Adonis, Dionysus, Attis and many other familiar figures from Greek mythology and classical antiquity were re-interpreted in this mold. The sacred king, the human embodiment of the dying and reviving vegetation god, was supposed to have originally been an individual chosen to rule for a time, but whose fate was to suffer as a sacrifice, to be offered back to the earth so that a new king could rule for a time in his stead.

Especially in Europe during Frazer’s early twentieth century heyday, it launched a cottage industry of amateurs looking for “pagan survivals” in such things as traditional fairs, maypoles, and folk arts like morris dancing. It was widely influential in literature, being alluded to by D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and in T. S. Eliot‘s The Waste Land, among other works.

Robert Graves used Frazer’s work in The Greek Myths and made it one of the foundations of his own personal mythology in The White Goddess. Margaret Murray, the principal theorist of witchcraft as a “pagan survival,” used Frazer’s work to propose the thesis that many Kings of England who died as kings, most notably William Rufus, were secret pagans and witches, whose deaths were the re-enactment of the human sacrifice that stood at the centre of Frazer’s myth.[5] An idea used by fantasy writer Katherine Kurtz in her novel Lammas Night.

Examples[edit]

- Devaraja, cult of divine kings in Southeast Asia.[6]

- Germanic kingship

- Holy Roman Emperor

- Imperial cult

- The Omukama of Kitara ruled as a heavenly sovereign.

- The High King of Ireland, according to medieval tradition, married the sovereignty goddess.

- The Eze Nri, title of the ruler of the defunct Igbo Nri Kingdom in present-day Nigeria. He was addressed as “Igwe,” meaning “heavenly one” in the Igbo language, and has[clarification needed] the pretender of a contemporary traditional state of the same name as his successor.

- The Emperor of Japan is known in Japanese as Tennō – “heavenly sovereign”.

- The Kende was the sacred king of the Magyars in the 9th century.[7]

- The Khagan (Ashina)[relevant? – discuss]

- The Kings of Luba became deities after death.

- The temporal power of the Papacy

- Pharaoh, title of Ancient Egyptian rulers. The pharaoh adopted names symbolizing holy might.

- King of Rome

- Rex Sacrorum

- Pontifex Maximus – a title inherited by the Papacy

- Roman triumph, according to legend first enacted by Romulus

- Augustus

- Son of Heaven, East Asian title

- Shah, Iranian title[relevant? – discuss]

- King of Thailand

- Tsar, Bulgarian title (later Russian)[relevant? – discuss]

- The pre-colonial emperors and kings of the Yoruba people, the obas, and their contemporary counterparts

Monarchies carried sacral kingship into the Middle Ages, encouraging the idea of kings installed by the Grace of God. See:

- Capetian Miracle

- Royal touch, supernatural powers attributed to the Kings of England and France

- The Serbian Nemanjić dynasty[8][9]

- The Hungarian House of Árpád (known during the Medieval period as the “dynasty of the Holy King”‘)

In fiction[edit]

Many of Rosemary Sutcliff‘s novels are recognized as being directly influenced by Frazer, depicting individuals accepting the burden of leadership and the ultimate responsibility of personal sacrifice, including Sword at Sunset, The Mark of the Horse Lord, and Sun Horse, Moon Horse.[10]

In addition to its appearance in her novel Lammas Night noted above, Katherine Kurtz also uses the idea of sacred kingship in her novel The Quest for Saint Camber.[11]

See also[edit]

- Apotheosis, glorification of a subject to divine level.

- Avatar

- Coronation

- Euhemerism

- Great Catholic Monarch

- Great King

- Greek hero cult

- Jaguars in Mesoamerican cultures

- Jesus in comparative mythology

- Katechon – Eschatological-Apocalyptic King

- Dying-and-rising god

- Monarchy of Thailand – Ayutthayan period

- Mythological king

- Rajamandala

- Sceptre

- Winged sun

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ Frazer, James George, Sir (1922). The Golden Bough. Bartleby.com: New York: The Macmillan Co. http://www.bartleby.com/196/1.html.

- Jump up^ Segal, Robert A. (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford UP. p. 61.

- Jump up^ Meletinsky, Eleazar Moiseevich (2000). The Poetics of Myth. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 0-415-92898-2.

- Jump up^ “CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Vicar of Christ”. www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Jump up^ Murray, Margaret Alice (1954). The Divine King in England: a study in anthropology. British Library: London, Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780404184285.

- Jump up^ Sengupta, Arputha Rani (Ed.) (2005). “God and King : The Devaraja Cult in South Asian Art & Architecture”. ISBN 8189233262. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- Jump up^ Gyula Kristó (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 136. ISBN 978-963-482-113-7.

- Jump up^ Даница Поповић (2006). Под окриљем светости: култ светих владара и реликвија у средњовековној Србији. Српска академија наука и уметности, Балканолошки институт. ISBN 978-86-7179-044-4.

- Jump up^ Sima M. Cirkovic (2008). The Serbs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4051-4291-5.

- Jump up^ Article about Rosemary Sutcliff at the Historical Novels Info website; paragraph 15

- Jump up^ Katherine Kurtz, The Quest for Saint Camber, ISBN 0-345-30099-8, Ballantine Books, 1986, p 360-363.

References[edit]

- General

- Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, (Blackwell, 1993): ISBN 0-631-18946-7

- William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, (London, 1875)

- J.F. del Giorgio, The Oldest Europeans, (A.J. Place, 2006)

- Claus Westermann, Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. sacred kingship.

- James George Frazer, The Golden Bough, 3rd ed., 12 vol. (1911–15, reprinted 1990)

- A.M. Hocart, Kingship (1927, reprint 1969)

- G. van der Leeuw, Religion in Essence and Manifestation (1933, English 1938, 1986)

- Geo Widengren, Religionsphänomenologie (1969), pp. 360–393.

- Lily Ross Taylor, The Divinity of the Roman Emperor (1931, reprint 1981).

- David Cannadine and Simon Price (eds.), Rituals of Royalty: Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies (1987).

- Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods (1948, 1978).

- Colin Morris, The Papal Monarchy: The Western Church from 1050 to 1250 (1989),

- J.H. Burns, Lordship, Kingship, and Empire: The Idea of Monarchy, 1400–1525 (1992).

- “English school”

- S.H. Hooke (ed.),The Labyrinth: Further Studies in the Relation Between Myth and Ritual in the Ancient World (1935).

- S.H. Hooke (ed.), Myth, Ritual, and Kingship: Essays on the Theory and Practice of Kingship in the Ancient Near East and in Israel (1958).

- “Scandinavian school”

- Geo Widengren, Sakrales Königtum im Alten Testament und im Judentum (1955).

- Ivan Engnell, Studies in Divine Kingship in the Ancient Near East, 2nd ed. (1967)

- Aage Bentzen, King and Messiah, 2nd ed. (1948; English 1970).

External links[edit]

- article Rex Sacrificulus in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- Sacred Kings, an ebook on sacred kingship in different cultures