Ancient Egyptian Architecture : Kom Ombo, 1838. David Roberts.

Jan 20, 2016

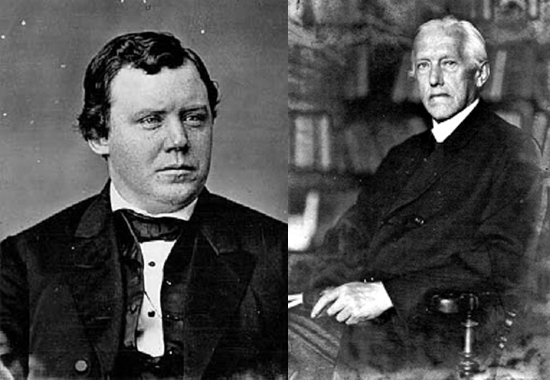

Criticized, ostracized, derided, scorned and rebuked; Cuvier and Schaeffer.

These two French eccentric geniuses ranged their new practical paradigms against the sanitized teachings of the Royal Society’s consensus science. Georges Cuvier and then later Claude Schaeffer, dared question the hidebound uniformitarian teachings demanded by the Royal Society’s geology darlings, Hutton and Lyle. They insisted that the world’s development was a slow evolutionary process explained by millions of years of uniform steady change. This misneme eventually influenced Darwin to explain evolution as a child of slow “natural selection” that, by chance, produced superior offspring and new species entirely through the agency of “survival of the fittest”. A gross simplification that has survived as a cherished dogma entrenched into every facet of modern science.

But what sets our two practical French geniuses apart?

Georges Cuvier was a child of the French and American Revolutions around the 1800’s. Probably nourished by this chaotic period of tumbling dogmas, he was able to study the incredibly rich layered fossil beds around Paris and beyond unhampered by convention. These distinctive layers revealed many beds of fossils plastered on each other by a succession of marine and then land based phyla of extinct and living flora and fauna. Those blunt separations signalled mass destruction upon destruction and sudden new speciation. He mainly accused catastrophic floods as the tool of these extinctions but then on his various trips to the United States he was intrigued by the mythology of the Native Americans. They spoke of cosmic lightning destroying the megafauna and earlier man.

From the Lakota nation cited by Erdoes and Oritz:

”The creator sang the song of destruction and sent down fierce Thunderbirds to wage a great battle against the other humans and giant animals. Finally at the height of the battle, the Thunderbirds suddenly threw down their most powerful Thunderbolts all at once. The fiery blast shook the entire world, toppling mountain ranges and setting forests and prairies ablaze. The flames leapt up to the sky in all directions, the world’s lakes boiled and the giant animals and evil people burned up where they stood. The Earth split open, sending great torrents across the entire world. The survivors found the bleached bones of the giant animals buried in mud and rock all over the world“

Adrienne Mayer, writing on the early white pioneer fossil hunters, claims they described America as a continent covered by ancient extinct giant fossil bones. Cuvier’s fundamental paradigms described a series of mass extinctions separated by marine and terra firma deposits. Species change followed each upheaval. His bone dissections plotted this in intimate detail. He was an obsessive examiner of every detail of fit and function. Extraordinarily meticulous observation, preservation and comparative deduction chartered his findings. Not only did this clash with the later Hutton and Lyle’s theories but even clashed with Bishop Usher’s fundamentalist theories on a seven thousand year old Earth only once cleansed by a Biblical flood.

The admirable Claude Schaeffer, who possessed many of Cuvier’s practical qualities, through his early excavations in Syria’s Ras Shamira and Enkomi in Cyprus, revealed sequences of civilizations separated by six destruction boundaries. Although artefacts such as pottery and jewellery were useful in discerning different periods of cultural development, he was more intrigued by what caused the instantaneous demise of these physically separated civilizations. Typically this had been attributed to destructive hordes of armies and raiders intent on pillage, destruction, rape and plunder. Theoretically they burnt and destroyed their enemy’s cities.

Schaeffer saw what others had not. Nature had played a major part in this drama. Walls and cities had been bent and twisted by earthquakes. Wild fires had left ashes sometimes many meters thick, unable to be explained by the burning of house timbers. Tsunami deposits were readily seen in Enkomi, Cyprus. Fierce wind deposits and destructive floods could be disseminated in the ruins. Climate change and reversion to nomadic wandering could even be inferred from the obvious footprints of abandonment and rebuilding. He cites indications of climatic catastrophes by pollen analyses, drop of ocean levels and land sinking. He examined over 90 sites in the Middle East and beyond and concluded that in the “Bronze Age “period alone there had been six destructive layers of varying intensity. Importantly he insisted that no catastrophes of this magnitude had been observed in recent times. This was clearly illustrated in his epic work, Stratigraphie Comparée etChronologie de l’Asie Occidentale.

Curiously, the equally lambasted Immanuel Velikovsky had come to similar conclusions from separate evidence. Velikovsky relied on ancient testimony and insights from many ancient sources. But he also understood that celestial mechanics was fundamentally influenced by electromagnetic drivers. This had been ignored by most cosmologists.

Schaeffer relied on the practical observations of an archaeologist with dirt on his hands. However, he too acknowledged, as had Velikovsky, the importance of ancient texts in researching fundamental cause. Both became friends due to their frustration with the dogmas of the day. Schaeffer commented to Velikovsky:

“You are working in the right direction and time will help to show the reality of global catastrophes. Already continental catastrophes cannot be doubted as I showed by my stratigraphical work in the Near East.”

Both Velikovsky and Schaeffer appreciated the value of Cuvier’s foundational work:

“You refer very well to Cuvier’s views which are too often forgotten nowadays. I feel exactly the same way, I know that those vast crises and cataclysms have occurred.“

The great minds of Cuvier and Schaeffer fully concurred on the reality of the crises but equally both searched vainly for a primal cause. Velikovsky was certainly not the first to propose a celestial cause but he was probably the first to nail electromagnetism as the essence of planetary dynamics and propose chaos in the cosmos as driven by this erratic fundamental. Thus amongst many others these three came together to offer a new driving paradigm to mankind’s fate.

However Schaeffer’s final words to Velikovsky reveals acceptance of this was not going to be an easy task.

“Many of my colleagues are not easily accessible to new ideas and use their arguments in order to discredit the whole idea of the reality of crises on continental scale. It disturbed their conservative and comfortable outlook on the historical events during the catastrophic events of earlier millenia. It will take more time until the new idea take root, but it will ultimately take root for the truth always in the end prevails.“

Peter Mungo Jupp

Films: www.mungoflix.com Articles: www.ancientdestructions,com