I. Temple, Crown, Vase, Eye, and Circular Serpent

A primary thesis of this book is that the Saturnian configuration provoked many different symbols, whose underlying relationship to a single cosmic form too often goes unnoticed.

When the ancients laid out the sacred city they sought to establish a likeness of the cosmic dwelling, a circle around a fixed centre. And in organizing the first kingdoms, unifying once-separate territories, the founders followed the same celestial plan.

There was only one dwelling of the great god, but this dwelling inspired imitative forms of varying scale and varying ritual functions. At root the creator’s home is simply “the place,” “the land,” “the holy abode,” or “the enclosure.” Only with the construction of imitative cities does the god’s residence become “the cosmic city.” And only after the organization of imitative terrestrial kingdoms can one meaningfully term the heavenly abode a “celestial kingdom.”

What the smallest city and grandest empire have in common is an identical relationship to the Saturnian enclosure. Distinctions of scale “down here” do not alter the fact that the celestial city and kingdom are absolutely synonymous.

In addition to the images of the Saturnian band reviewed in the foregoing sections, several others require attention.

The Temple

Like the ancient city and kingdom, the terrestrial shrine copies Saturn’s dwelling. (Saturn, as we have seen, founded the “first” temple.) Though the local temple acquired its own special functions and attributes, the ritual leaves no doubt that the cosmic “house,” “shrine,” and “chamber” mean the same thing as the “city of heaven.”

Sumerian texts describe the cosmic city of Eridu as:

The house built of silver, adorned with lapis lazuli . . .

The abyss [cosmic ocean],

the shrine of the goodness of Enki, befitting the divine decrees,

Eridu, the pure house having been built.691

Conversely, the celestial temple is called “the primeval city” (the very title of many Sumerian cities themselves), and the hymns say of the Kes temple:

Indeed it is a city, indeed it is a city, who know its interior?692 The Kes temple is indeed a city,

who knows its interior?

Enki, the Sumerian Saturn, erects his temple or “sea house” as the crowning act of creation:

After the water of creation has been decreed, After the name hegal (Abundance), born of heaven, Like the plant and herb had clothed the land, The lord of the abyss, the King Enki,

Enki, the lord who decrees the fates, Built his house of silver and lapis lazuli:

Its silver and lapis lazuli, like sparkling light. The father fashioned fittingly in the abyss.693

This is the “far-famed house built in the bosom [heart, centre] of the Nether sea.”694 The cosmic dwelling becomes the “Good temple built on a good place . . . floating in the sky . . . heaven’s midst.” 695 It is said to “float like a cloud in the midst of the sky.”696

In constructing the earthbound copy of the temple above, states Jastrow, the Babylonians strove to make both the exterior and interior “resplendent with brilliant colouring—‘brilliant as the sun.’”697 The purpose is clear: to imbue the local temple with a lustre matching that of the prototype. Symbolically, the local temple takes on the radiance of the celestial, becoming the “house of light,” “house of the brilliant precinct,” or “lofty and brilliant wall”; “the house of great splendour,” “the beautiful house,” “the brilliant house.”698

To deal with the Sumero-Babylonian imagery in its own terms one must understand the cosmic temple not only as the god’s house—but more. The temple fashioned in the abyss is the created “earth.” The Sumerian Ekur, the house of Enlil on the cosmic sea Apsu, means both “temple” and “earth” (“land,” “place”).699

Gragg confirms the identity of the cosmic temple and the created “earth” when he notes “the cosmic dimensions of the temple. It fills the whole world.”700 The Sumerians celebrated the god’s shrine as the “pure place, earth of An” (that is, Saturn’s Earth).701

Throughout the previous sections I have contended that Saturn’s dwelling produced the original myth of the lost paradise. That the great god’s house enclosed the cosmic land of fertility and abundance is the straightforward declaration of the Sumerian temple hymns. (Though some of the lines in the following quotes are broken, one cannot fail to discern the consistent theme):

House, Mountain, like herbs and plants beautifully blooming

. . . your interior is plentitude.702

The temple is built; its abundance is good!

The Kes temple is built; its abundance is good!703

House with well-formed jars, set up under heaven . . .

(Full of) the abundance of the midst of the sea . . .

Emah, the house of Sara, the faithful man has enlarged for you (Umma) in plenty . . . (With) good fortune it is expanding, (its)

. . . abundance and well-being . . .704

House . . . from your midst (comes) plenty,

Your treasury (is) a mountain of abundance . . .705

Your interior is the place where the sun rises, endowed with abundance, far-reaching . . .706

House with the great me’s of Kulaba . . . ,

(its) . . . has made the temple flourish,

Well grown fresh fruit, marvellous, filled with ripeness, Descending from the midst of heaven . . .707

One sees that the temple stands at the cosmic “midst” or centre. From its interior shines the primeval sun, It houses the flourishing celestial garden.

The chamber of the great god, according to Sumerian creation myths, was that in which dwelt the original generation of “men” (i.e., the company of gods to whom all races traced their ancestry and from which each race took its name). The chamber was the prototype of Eden, the ancestral birthplace.

In the Sumerian myth of the primordial hero Tagtug occurs a lively description of the god’s chamber as a celestial garden. Occupying the house of abundance are the Anunnaki, the great god’s companions. And here came into being the first generation of “Mankind”:

The abundance of the goddess of flocks and of the Grain Goddess, The Anunnaki in “the holy chamber”

Ate and were not filled . . .

The Anunnaki in “the holy chamber”

Drank and were not filled.

In the holy park, for their (the god’s) benefit, Mankind with the soul of life came into being. Then Enki said to Enlil:

“Father Enlil, flocks and grain

In “the holy chamber” have been made plentiful.

In “the holy chamber” mightily shall they bring forth.”

By the incantation of Enki and Enlil

Flocks and grain in “the holy chamber” brought forth.

Pasture they provided for them abundantly,

For the Grain-goddess they prepared a house . . .708

The flowering of the celestial garden is a widespread theme which I touched on briefly in the earlier discussion of the Egyptian creation and which I intend to explore at greater length in a subsequent volume. It is surely worthy of note, however, that the great god’s “chamber” is the same as the “holy park” in which “Mankind” was brought forth.

If one reads the above lines in the light of the Egyptian symbolism—which equates the first generation of gods (men) with the “abundance” erupting from the creator—the Sumerian myth takes on greater meaning than might otherwise be evident. Immediately after the statement, “Mankind with the soul of life came into being,” Enki declares that “flocks and grain in ‘the holy chamber’ have been made plentiful.” The primeval generation was the same thing as the overflowing abundance, both referring to the luminous debris which erupted from the creator as “speech.” Thus the “flocks and grain” of the celestial garden, according to the Sumerian text, are brought forth “by the incantation [i.e., speech] of Enki and Enlil” (two competing figures of the single creator). To my knowledge, such close parallels between the Egyptian and Mesopotamian creation accounts have never received adequate attention by comparative mythologists.

The blossoming chamber of the Sumerian creation also finds a counterpart in a Hawaiian genesis myth, reproduced by Leinani Melville:

Man descended from the Sacred Shrine of The King who created the heavens.

The Shrine of the King of Heaven who caused that distant realm to bloom and flower:

The Consecrated Realm of Teave, the World of Teave.709

Both the Hawaiian and Sumerian sources place the genesis of the race in the great god’s shrine or chamber, likened to a flowering garden. Just as the Sumerian chamber or temple corresponds to the “earth,” so does the Hawaiian sacred shrine answer to “the World of Teave.”

The Egyptian Temple

As in Mesopotamia, Egyptian sources portray the primeval temple as the visible dwelling of the sun-god: May I shine like Re in his divine splendour in the temple.710

Homage to thee [Osiris Nu], O thou who art within the divine shrine, who shinest with rays of light and sendest forth radiance from thyself.711

. . . Every god shall . . . rejoice at the life of Ptah when he maketh his appearance from the great temple of the Aged One which is in Annu.712

Thou art the ruler of all the gods and thou hast joy of heart within the shrine.713

The great god’s shrine, house, or temple is the band of “glory,” the Aten : “Your pavilion is enlarged in the interior of the Aten,” states a Coffin Text.714

When the Egyptians laid the foundation of a temple, they consecrated the enclosed ground as “the primeval territory of the domain of the sun-god.” Each temple became a miniature of the cosmic habitation founded in the creation. Thus the Egyptians viewed the Edfu temple as “the veritable descendant of the mythical temple that was created at the dawn of this world . . . ,”715 Reymond tells us.716 The foundation ground became “the Blessed Territory from the time of the Primeval Ones . . . , the Hinterland of the Primeval Water.”717 This was the Province of the Beginning, “the Blessed Homeland.”718

In Hebrew cosmology, reports Wensinck, “the sanctuary is the type and representation of Cosmos and Paradise and as such a power diametrically opposed to Chaos.”719

From the very spot of the Hebrew temple “the first ray of light issued and illuminated the whole world.” Indeed, the temple was the “whole world,” according to a Midrash: “The temple corresponds to the whole world.” 720 Tradition states that the primordial light was “not identical with the light of the sun, moon and stars,” but lit up the temple from its centre and radiated out through the windows.721 The cosmic temple, in other words, was the lost land of the “dawn” or first “sunrise.”

Temple and Womb

Nothing is more basic to the imagery of the temple than its identity as the cosmic womb. Neumann observes: “Just as the temple is . . . a symbol of the Great Goddess as house and shelter, so the temple gate is the entrance into the goddess; it is her womb, and the innumerable entrance and threshold rites of mankind are expressions of this numinous feminine place.” 722 Throughout the Near East, states Allegro, “the temple was designed with a large measure of uniformity” and this sacred abode is “now recognizable as a microcosm of the womb.”723

Not in one land, but in every segment of the world, the sacred texts confirm this identity of temple and womb. The Egyptian great god resides within the womb of the goddess as in a “house” or “chamber.” The goddess Hathor is “the house of Horus.”724 The name of Isis means chamber, house, abode, etc., and the Egyptians claimed she was the house in which Horus came into being.725 Nut is “the good house,”726 and Neith the house of Osiris,727 while the name of Nephthys means “Lady of the House.”

The identity stands out in this hymn to Re: “I am exalted like the holy god who dwelleth in the Great Temple, and the gods rejoice when they see me in my beautiful coming forth from the body [khat, womb] of Nut, when my mother Nut giveth birth to me.”728 To shine as the “sun” within the cosmic temple is to come forth within the womb of Nut, “the good house.”

Among the Egyptians, notes Sethe, “house” served as a poetic expression for the womb.729 Clearly, this “poetic expression” originated as a radical identity in the ritual. Just as the goddess’ titles denominate her the “house” or “temple” of the great god, so does the temple receive the character of the goddess. Ptah’s temple at Memphis is the “mistress of life,”730 and an inscription in King Seti I’s funerary temple states, “I am thy temple, thy mother, forever and forever.” 731 The Holy Chamber from which Re shines forth is, according to Piankoff, “The Holy Chamber of the Netherworld [Tuat], the womb of divine birth.”732

Throughout Mesopotamia, one discovers the same features of the temple. Here, too, the cosmic “house” appears as the womb of primeval genesis. Urukug is “the shrine which causes the seed to come forth,”733 while the temple of Aruru is “the procreative womb of Emah”734 and the temple of Lilzag “the house of exalted seed.”735

The Mesopotamian temple or chamber thus gives birth to the god. Tammuz, the man-child, is “the offspring of the house”736 and Marduk the “Child of the holy chamber.”737 In the Babylonian creation epic we read:

In the chamber of fate, the abode of destinies,

A god was engendered, most able and wisest of gods.

In the heart of the Apsu was Marduk created.738

“You have taken my seed into the womb, have given birth to me in the shrine,” declares King Gudea to the goddess Gatumdug. 739 One can compare the Sumerian text: “In the great house he has begotten me.”740 As in Egypt, the gate of a sanctuary is conceived as the entrance to the womb of the goddess.741 Hence, Sargon styles one of the gates of his palace Belit ilani, “mistress of the gods.”742

The Crown

Among all ancient races the crown, wreath, or headband signified religious and political authority. Yet this world-wide function of the crown reflects no self-evident fact of human nature or of the external world. What was the source of the crown’s numinous powers?

The symbols of kingship have their origin in the Universal Monarch, the ancestor of kings and “founder” of the kingship ritual. Legends of the great god say that, when he established his kingdom, he wore as a crown his “circle of glory” (halo, aura). Before Egyptian rulers ever donned the White Crown, the crown of the great father Osiris shed its light at the cosmic centre: “His crown clove the sky and consorted with the stars.”743 The primordial sun, reports Pliny, “established civilization and first triumphantly crowned heaven with his glowing circle.”744 In the ritual of the Mandaeans it was the “First Man” who wore as a crown the “circle of radiance, light and glory.”745 One could hardly make a greater mistake than to assume, with so many modern scholars, that the crowns worn by gods are simply projections onto the heaven order of the crowns worn by terrestrial kings. Divorced from the crown of the Universal Monarch, the headdress of the local king becomes a meaningless artifact. Whatever powers the crown may possess, they derive from the cosmic prototype.

Fundamentally, the crown is an enclosing band. The most important component of the Egyptian crown was the gold headband, while the great god was “Master of the Head-Band.”746 The Sumerian word for crown, uku, means “great band.”747 In the classical etymologies reviewed by Onians the “crown” possesses the concrete meaning of a “circle” or “band” enclosing a god or a man.748

When the Egyptian priests placed the sacred band on the head of the king, deeming him the regent of the sun- god Re, they were guided by the image of the great god himself, whose hieroglyphic was , showing the sun- god in the circle of the Aten. Thus, in the Theban ritual, the gods Horus and Set say to the new king, “I will give thee a life like unto that of Re, years even as the years of Tem,” and “I will establish the crown upon thy head even like the Aten on the head of Amen-Re.”749

The great god not only wears the crown of glory, he dwells in it. He “appears in the White Crown”750 or “comes forth from the Very Great Crown.”751 In the Book of the Dead one finds “the divine being who dwelleth in the nemmes crown”.752

More specifically, the god’s crown is his spouse—the womb-goddess who emanated from the god, yet gave birth to him.

O Red crown, O Inu [the crown], O Great One . . .

O Inu, thou hast come forth from me; And I have come forth from thee.753

To wear the crown is to reside within the womb; or conversely, to be born in the womb is to wear the crown. 754 It is in this sense that one must understand the statement of the Coffin Texts that the god is “born” in the crown or that the king is “the son of the white crown.”755 The same identification of crown and womb explains the statement that Osiris first shone forth “fully crowned from his mothers womb.”756 Does not the sign depict the “fully crowned” god within the cosmic womb?

“I am he who is girt about with his girdle and who cometh forth from the goddess of the Ureret crown.” 757 This statement from the Book of the Dead concurs with numerous other references in Egyptian texts, equating the crown with the mother goddess. In the Pyramid Texts we read: “I know my mother, I have not forgotten my mother, the white crown.”758 The same texts say of the king: “thy mother is the Great Wild Cow, living in Nekeb, the white crown, the Royal Headdress.”759 Accordingly, the Egyptians esteemed the goddess Isis as “the Crown of Re-Horus”760 and the goddess Tefnut as the “diadem of Re.”761

The identity of goddess and crown, has, in fact, been fully acknowledged by Clark and Frankfort, among others.762 Yet Frankfort’s explanation amounts to this: “The goddess is simply the personification of the power of royalty . . . and hence is immanent in the crown.”763 The statement tacitly assumes that the local crown came first (who knows why) and that the great goddess, personifying an abstract “power of royalty,” came to be identified with the crown simply because the crown was a symbol of royal power.

But the relationship of the crown and womb amounts to a radical identity; both take their character from the same visible band. Ignored by Frankfort is the explicit equation of both the goddess and the crown with the circle of the Aten.

That the god dwells in the crown means that the crown is the god’s house or temple—what the Egyptians called “the temple of the White Crown.” Speaking of the headgear of Sumer and Egypt, Levy notes that “in each case it bears a relation to the monuments. It [the crown] may, in fact, be considered as itself a little sanctuary.” 764 But what was the source of this unexpected identity? Sumerian temple hymns repeatedly invoke the cosmic temple as the great god’s crown. The temple of Eqaduda is the “Crown of the high plain”765 and Sippar the “Sanctuary of heaven, star of heaven, crown, borne by Ningal.”766 The Kes temple becomes the “Great, true temple, reaching the sky, temple, great crown, reaching the sky . . .”767

The same identity prevails elsewhere. Hentze, observing that the Mexican Quetzalcoatl wears his temple as a crown, reports that such symbolism pervades early Chinese bronzes. One notes also the “world house” worn as a crown by the famous Diana of Ephesus. Like the sacred abode of all great gods the latter crown-temple has four doors facing in four directions.768

Since the cosmic temple is the same thing as the cosmic city, one should not be surprised to find that the city also appears as the crown. In the Book of the Dead occurs a description of “Re when at the beginning he rose in the city of Suten-henen [Heracleopolis], crowned like a king in his rising.”769 The evidence suggests that the city (or kingdom) in which Re first shone forth was the very circle of glory which he wore as a crown—and this is why, in the symbols and , the Egyptians combined the hetch-crown and tesher-crown with the symbol of the

goddess Nut , the “city” or “holy land.” In accord with this identity the Babylonian hymn proclaims, “Borsippa [the cosmic city] is thy crown.”770

Often the crown takes the form of a city wall. The most famous example, perhaps, is the crown of Tyche of Antioch, which corresponds to the turreted wall of the city.771 Concerning the goddess of the city-crown, Suhr writes: “ . . . the whole city wall, in a diminutive version, was placed on her head, beginning with Astarte and continuing with Aphrodite of Greek and Roman times.772 Yet why the crown was assimilated to the city wall remains unexplained by modern researchers—and will continue to remain a puzzle until scholars acknowledge the concrete form of the mother goddess, city, and crown as a single band of light around the great god.

The Vase

Mythmaking imagination also expressed the Saturnian band as a vase or receptacle housing the sun-god and his waters of life: all the waters of the world, according to ancient belief, originated in the solitary god.

As a symbol of the all-containing receptacle above, the round vessel became a popular figure of the mother goddess. “ . . . The great goddess as divine water jar is the mistress of the upper waters.” observes Neumann.773

- Elliot Smith notices the close connection of the mother goddess with the vase: “The idea of the Mother Pot is found not only in Babylonia, Egypt, India, and the Eastern Mediterranean, but wherever the influence of these ancient civilizations made itself felt. It is widespread among the Celtic-speaking peoples . . . It became also a witch’s cauldron, the magic cup, the Holy Grail, the font in which a child is reborn in the faith, the vessel of water here being interpreted in the earliest sense as the uterus or the organ of birth.”774

- The goddess Nut as the revolving water container

The vase, in the Egyptian hieroglyphs, denotes the celestial goddess Nut and the female principle in general.775 An interesting Egyptian illustration depicts Nut, bearing the cosmic vessel on her head, and spinning around with sufficient speed to cause drops of water to fly outward (see fig. 29).

The mother goddess is the revolving water container in heaven. Sumero-Babylonian cylinder seals show the purifying waters of the Apsu descending from a vase, regarded as the mother womb. The vase is in “the heaven of Anu,” called “the place of the flowing forth of the waters which open the womb.”776

The same symbolism of the vase prevails in China, according to Hentze (who relates the symbolism of the feminine container to a global tradition).777 The Zuni address the sacred pot as “the Mother,”778 while a Peruvian jar covered with breasts on all sides obviously expresses the identical theme.779

Thus does the sun-god dwell in the vase, renewing his birth each “day”: “I have come forth from my djenit-jar, and I will appear in the morning,” reads an Egyptian Pyramid Text.780 (I remind the reader that archaic “day” means our “night.”) To the same symbolism belongs the Hindu Vasishtha who is “born from the jar”781 and is obviously akin to the Iranian Fravashi Khumbya, “the son of the jar.”782 Muslim tradition echoes this theme in declaring that the soul of Mohammed preexisted in a vase of light in the world of spirits.783 The Chinese alchemist Wei Po-Yang says: “The True Man living in a deep abyss, floats about the centre of the round vessel.”784 The mother vase housing the manchild appears even in Mexico (fig. 31).785

Among the Mayans, writes Nuttall, the vase symbolized “the divine essence of light and life proceeding from ‘the Heart of Heaven.’786 “ Appropriately they designated the symbolic vase as the “navel or centre,”787 a characterization which agrees with Neumann’s interpretation of the vase as the “centre from which the universe is nourished.”788

The vase denotes, in other words, the celestial earth, the original land of abundance. While the Egyptian priests of Ptah claimed the primeval land to have been fashioned by Ptah on his potter’s wheel, the hymns also extol “the

pottery which Ptah moulded”789 in clear reference to the same primordial enclosure: the subject is the realm of the ancestors, where the resurrected dead receive “the fresh water in a jar which Ptah has fashioned.”790

16. The mother goddess as water container. Vase from Troy, fourth stratum.

- Man-child in vase. From Mexico, Vienna Codex

Here is the declaration of “the potter” in the Pyramid Texts (as translated by Faulkner): “I am your potter upon earth . . . I have come and have brought to you this mansion of yours which I built for you on that night when you were born, on the day of your birth- place; it is a beer-jar (sic!).”791 Most instructive is Faulkner’s parenthetical “sic!” following the phrase “beer-jar”—as if to suggest that the scribe suffered a lapse of reason: what could a beer jar have to do with the great god’s “mansion” and “birthplace”? Among the Egyptians beer symbolized fertility and abundance flowing from on high. The ritual “beer-jar” was the primeval land—the dwelling which congealed around the great father and (as the cosmic womb) “gave birth” to him. The same texts in which the above lines appear locate the potter god in “this Island of Earth.” Vessel, temple, earth, and womb denote the same celestial enclosure.

The Eye

One of the most mysterious symbols which have come down to us is the solitary and all-seeing Eye. In ancient Egypt, where the most complete information is available, the symbol pervades the monuments and the sacred texts of all periods. “The Eye is the key to the religion,” states Clark.792 Yet no archaic sign has been less understood than the mystic Eye: “The Eye is the commonest symbol in Egyptian thought and the strangest to us.”793

Is the Eye, as almost uniformly asserted, the solar orb? Nowhere is the weakness of solar mythology more apparent than in its handling of this puzzling symbol. One Egyptologist after another, by following the solar interpretation, passes over in silence the many enigmatic particulars of eye symbolism.

To my knowledge the only well-known authority to reject categorically the solar interpretation is Rudolph Anthes. After devoting extensive research to the Eye of Re, Anthes concludes that the Eye “apparently never was the sun.”794 Yet Anthes, seeking an answer in the heavens as they appear to us today, does not begin to unravel the interconnected symbolism of the Eye.

Strictly speaking the Egyptian Eye is neither a “sun” nor a “star,” but the circle or enclosure fashioned by the creator as his celestial home. The great god resides in the Eye as the pupil. One of the most common names of the Eye in Egypt is Utchat, hieroglyphically rendered as . The Utchat hieroglyph combines three closely related signs: 1) , meaning “to see” and also “to form, fashion, create”; 2) , “to fashion, encircle”; and 3) , “cord, to bind, to encircle.” The all-seeing Eye is the created enclosure, the bond around the primeval sun.

Thus the god has his home in the Utchat (Eye): “I am in the Utchat.”795 “I am he who dwelleth in the Utchat.”796 “Enter thou in peace [em hetep, “at rest”] into the divine Utchat.”797

A Coffin Text reads, “I am Horus in his Eye,”798 while the Harris Magical Papyrus states, “I am Shu under the form of Re, seated in the middle of his father’s eye.”799 In the Book of the Dead one finds: “I am the pure one in his eye”;800 “I am he who dwelleth in the middle of his own Eye.”801

Thus does the great god reside in the enclosure of the Eye as the “pupil.” “Praise be to thee, O Ra, Exalted Sekhem, aged one of the pupil of the Utchat [Eye].”802 “I am in the Utchat . . . I sit in [em, “as”] the pupil of the eye . . . ;”803 “God-the-pupil-of- whose-eye-is-terrible is thy name . . .”

When the texts speak of “the Eye of ‘Re who is in his Aten,”804 one recognizes that the Eye is the Aten, for the Egyptians treated the Eye sign and the Aten sign as interchangeable symbols. Just as the Aten constituted the protective enclosure, so did the Eye: “O Osiris Nu, the Eye of Horus protecteth thee, it keepeth thee in safety . . .” 805 “ . . . He is Horus encircled with the protection of his Eye . . .”806 “My refuge is my Eye, my protection is my Eye . . .”807 “I am the dweller in the Eye; no evil or calamitous things befall me.”808

Such references surely indicate that the Eye is not the sun or the sun-god, but the goddess, in whose protective womb the sun-god dwells. As a matter of fact, though Egyptian ritual presents the goddess under many names, all primary figures of the goddess receive the appellation “Eye of Re.” This includes, among others, Isis, Hathor, Nut, Sekhet, Iusaaset, Mehurt, Bast, Tefnut— and of course, the goddess Utchat (“Eye”).809

“The complex meshes of eye symbolism,” states Clark, “are woven all around the Egyptian Goddess and she cannot be understood or compared with other goddesses until they are unravelled.”810 Yet, while Clark notes several interesting associations of the Eye and goddess he fails to discern the Eye’s root character, as the protective enclosure.

Only the direct identity of the Eye and cosmic womb will explain its context in the ritual: “The child who is in the eye of Horus, hath been presented to thee . . .”811 “I am he whose being has been moulded in his eye.”812 Horus is said to “ . . . rear and nourish the multitudes through that Unique Eye, Mistress of the Divine Company and Lady of the Universe [All, Cosmos].”813

The very goddesses whom the texts depict as the Eye of the primeval sun are also called the “house,” as we should expect. As to the identity of the Eye and the temple, Egyptian sources leave no room for debate (though I know of no Egyptologist to observe the connection). The temple of Karnak is “the healthy eye of the Lord of All,” 814 a striking parallel to the Sumerian temple as the “House, eye of the land.”815

In the Book of the Pylons Re hearkens back to the remote age when “I was in the temple of my eye,” 816 while the Book of the Dead speaks of the son of Osiris residing “within the temple of his

- The eye of the resting

Eye in Annu.”817 Elsewhere one finds the primeval sun coming forth “in the sanctuary of my eye.”818

Of course no one who automatically thinks “sun” when reading “eye” is likely to reflect on the overlapping symbols of the eye as a band or enclosure. Nor can one so trained meaningfully explain why, throughout Egyptian ritual, the eye appears in conjunction with the crown. In the Egyptian mystery play, the king is commanded, “take thou thine eye, whole to thy face,” and the command is carried out by placing the crown upon the king—for the crown, as “the symbol and seat of royal power . . . is called the eye of Horus.”819

The Pyramid Texts say, “Horus has given you his eye that you may take possession of the Urert-Crown.”820 “O king, stand up, don the eye of Horus . . . that you may go forth in it, that the gods may see you clad in it.”821 As to the identity of Eye and crown one could not ask for more explicit statements than these: “I wear the white crown, the eye of Horus.”822 “O Osiris the king, I make firm the eye of Horus on your head—a headband.”823 “I give you the crown of Upper Egypt, the eye which went up from your head.”824 (The circle of glory issued from the central sun.)

If the god wears the Eye as a crown, so also does he take the Eye as a throne, and this relationship of the Eye and throne helps to explain the hieroglyph for Osiris, in which the two symbols appear together . But to conventional schools the combination makes little sense. In Budge’s opinion, for example, there is no clear basis for the assimilation of the two signs, and “the difficulty is hardly likely to be cleared up.”825

Yet to anyone aware of the interrelated images of the Aten , the Osiris hieroglyph will pose no mystery. The throne is the symbol of Isis (i.e., Isis is the throne), but the same goddess appears as “the eye”—so that Osiris sits enthroned within the circle of the Eye. Indeed, the Egyptian language says as much when it terms the throne ast utchat—“the throne of the Eye.” And the Book of the Dead brings the Eye and throne into connection with the crown and egg: “I am the lord of the crown. I am in the Eye, my egg . . . My seat is on my throne. I sit in [em, “as”] the pupil of the eye.”826

Though the influence of the Eye was felt far beyond Egypt, it is the integrated Egyptian imagery that throws light on later developments of the symbol. While the texts sometimes speak of “two eyes” (see the section on the cosmic twins), fundamentally there is only one Eye of the great god. “I am Re who wept for himself in his single eye,” 827 states the Coffin Texts. The single Eye of Re or Horus is paralleled by the “clear-seeing eye” of the Sumerian Enki, 828 the single eyes of the Norse Odin,829 the Iranian Ahura Mazda,830 and the Mexican Tlaloc,831 the “ageless eye of all-seeing Zeus,”832 and the “one-eye of heaven” belonging to the Japanese Ama no Ma-hitotsu.833

The Egyptian Eye of Horus, in the Book of the Dead, is that which “shineth with splendours on the forehead of Re.”834 One can easily understand how subsequent generations, possessing only conceptions rather than perceptions to guide them, gave the great god increasingly human form, translating the central Eye into the legendary “third eye,” which in Hindu representations appears as little more than a decorative jewel. The single eye of the Cyclops belongs to the same class of images. If the eye is not centered on the forehead, it may be located on the breast, as in the case of the Hindu demon Kabandha, slain by Rama,835 and the headless man encountered by Fionn, Oisin, and Caoilte in Celtic myth.836 (The pupil of the Eye is the Heart of Heaven.)

Surely one cannot properly evaluate the fanciful one-eyed giants of the classical and medieval age without first taking into account the celestial Eye—which left a mighty imprint on the earliest ritual.837

The Cyclops, or “wheel-eyed” giant, corresponds in many ways to the god Odin, of Norse mythology. Odin’s all-piercing eye is also “a giant wheel.”838 In ancient cosmology nothing is more explicit than such imagery of the enclosed sun. If the experts have failed to unravel the mystery of the Eye or Eye-wheel , the failure is not due to a lack of evidence but to the habit of the researchers, who, from the start, excluded the enclosure from the mythological investigation.

The Circular Serpent

19. Saturn as Mithraic Zurvan (Time), with central eye. (Pupil of eye=heart of heaven.

It would be quite impossible, within the limited space permitted here, to review all the interconnections unifying the imagery of the Saturnian band. For every instance previously cited, many others have been left out simply to avoid excessive monotony.

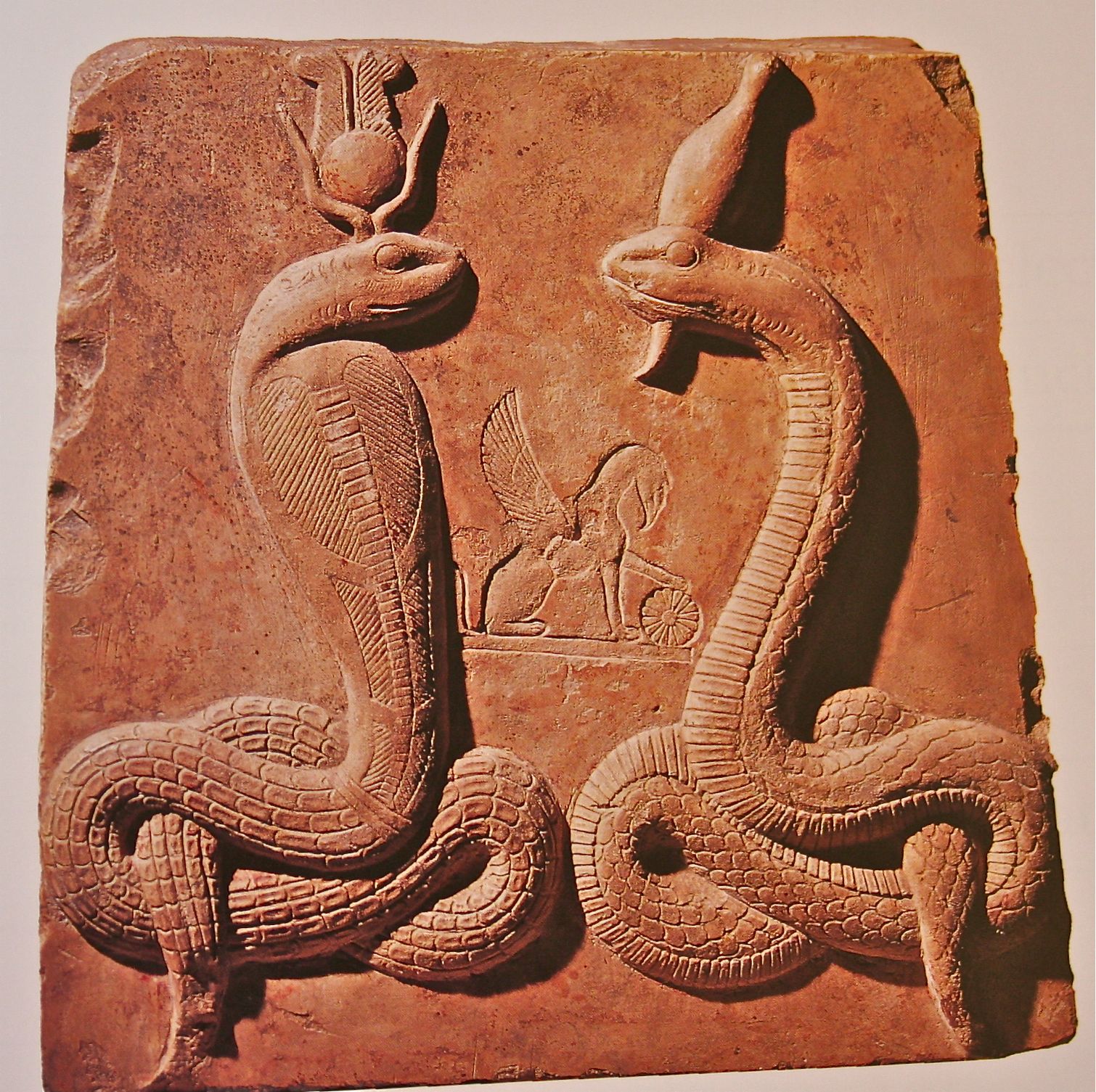

As a final example of overlapping imagery, I shall cite the case of the circular serpent. All of the Saturnian gods

—Atum-Re, An, Yama, Huang-ti, Quetzalcoatl, Kronos—reside within the fold of a serpent (dragon, fish, crocodile, etc.). But this symbol cannot be evaluated in isolation from the celestial earths, eggs, wheels, temples, crowns, and eyes which fill the ancient lexicon.

In the general mystic tradition, reports Cirlot, “the dragon, the serpent or the fish biting its tail, is a representative of time.”839 Father Time, of course, is Saturn. Thus the Greeks placed in the hands of Chronos a snake which formed a ring by holding its tail in its mouth,840 and this circular serpent is clearly that which the Hindus called Kali (“Time”). The Zoroastrians represented Zurvan (“Time”) by an enclosing serpent. A serpent encircles a Nahuatl calendar wheel (wheel of time) published by Clavigero.841 On the famous Mexican calendar stone twin serpents form a single enclosure around the stone.842

The Egyptians associated the circular serpent with Atum (god of Time), identifying the serpent with the cosmic waters erupting from the creator: “I am the outflow of the Primeval Flood, he who emerged from the waters,” the serpent announces.843

The water serpent, issuing from Atum, constituted an aspect of the creator, eventually forming a coil around

“himself”:

I bent right around, I was encircled in my coils,

One who made a place for himself in the midst of his coils. His utterance was what came forth from his mouth.844

Why the reference to the “utterance” of the god in association with the appearance of the serpent-coil? The reason is that the serpent, embodying the “outflow” of erupting waters, was himself a manifestation of the creator’s speech.

In the Coffin Text, the great god, or Master of the All (Cosmos), recalls the original age “while I was still in the midst of the serpent coil.”845 And the king hopes to attain this very enclosure: “The King lies down in your coil, the King sits in your circle” proclaims a Pyramid Text.846

Can this serpent be anything other than the band of the enclosed sun ? The sun-god Re, while deemed ami khet, “dweller in the fiery circle,” is also ami-hem-f, “dweller in his fiery serpent.” Do not the circle and the serpent mean the same thing? The hieroglyphs offer conclusive evidence. Though the common pictograph of Re is , the Egyptians also denoted Re by the glyph , showing the serpent as the band around the primeval sun.

This direct identification of the serpent and the circle of the Aten enables us to test the coherence of Aten symbolism as a whole. For if the serpent denoted the band of the enclosed sun one should find:

1. That the serpent was the circle of the mother goddess and defined the limits of the All (i.e., the cord, egg, shield, or belt of Saturn’s Cosmos).

- That the serpent enclosed the world-wheel, city, throne, earth-navel and celestial

- That the same serpent formed the wall of the cosmic temple, encircled the god-king as a crown, enclosed the celestial waters as a vase, and defined the circle of the all-seeing

- Egyptian and Mayan versions of the circular serpent as water

Throughout all of ancient Egypt the circular serpent was the symbol of the great mother. In the hieroglyphs, the Uraeus serpent, often used in conjunction with an egg, means “goddess.” “The goddess Uatchet cometh unto thee in the form of the living Uraeus, to anoint thy head . . . ,” reads the Book of the Dead.847 A Karnak temple inscription states that the goddess Mut, in the form of a serpent, encircled “her father Re and gave birth to him as Khonsu.”848

In the same way the Babylonians knew the great goddess as “the mother python of heaven.”849 The Cosmos, according to Jeremias, was represented as the womb of the “shining Tiamat,” the enclosing serpent or dragon of the primeval sea.850 So also did the Hindus, Cretans, Celts, Greeks, Romans, and Mexicans represent the mother goddess as a serpent or dragon.851

It is the same thing to say that the circular serpent enclosed Saturn’s Cosmos. In the Egyptian language the “coil” formed by the serpent is literally “the cord” or “the band,” indicated by the hieroglyphs and . The serpent itself was the rope which the creator stretched round about, gathering the primeval waters or primeval matter into an organized enclosure.

- Circular dragon in Haropollo, Selecta hieroglyphica (1597)

36. The alchemist circular dragon

- Mexican circular serpent biting its tail

- Circular serpent motif on the interior of a food basin from Sikyatki in the South-Western United States

39a&b. Two Chinese versions of the circular dragon.

39b. The dragon encloses the central sun.

- Hindu circular serpent, enclosing the bindu, or central sun

41. Alaska circular serpent, indicating close relationship to enclosed sun

In Sumero-Babylonian imagery, too, a circular serpent—called “the rope of the great god”—encloses the original Cosmos.852 The serpent-rope is “the bond of the All” held by Enki or Ninurta (Saturn).

But the cord is synonymous with the cosmic egg and girdle, and this conjunction of Saturnian symbols makes particularly interesting the statement of the Greek philosopher Epicurus to Epiphanius: “ . . . the All was from the beginning like an egg, and the pneuma [World Soul] in serpent wise around the egg was then a tight band as a wreath or belt around the universe.”853 The Orphics called this serpent Chronos, describing it as the bond (peirata) of the Cosmos. The serpent- bond “lies around the Cosmos,” proclaimed the Pythagoreans.854 It was thus an ancient custom to display images of the cosmic egg encircled by a vast serpent.

All the evidence in the foregoing sections indicates that this circle of the Cosmos was the “earth” or “place” fashioned in the creation. Hence, the serpent who circumscribes the organized All is the same serpent whom the ancients depicted encircling the created “world.”

In the Gnostic work Pistis Sophia, Our Lord states, “The outer darkness is a great serpent, the tail of which is in its mouth, and it is outside the whole world.”855 As shown by Budge, the idea had its roots in Egypt, where the world-encircling serpent was Apepi, “a serpent with his tail in his mouth.”856 Horapollo reports that when the Egyptians wished to depict the “world,” they painted a serpent.857

The Babylonian Esharra, the circle of created “earth,” is identified as the primordial beast Tiamat858, the world-enclosing serpent- dragon which the Hebrews called Tehom and the Muslims the “Mysterious Serpent.”859 To the Hindus it was the fabulous serpent Naga that enclosed the world in its folds. Scandinavian myth knew the serpent Midgard, the Weltumspanner, or “Stretcher-round-the-World.”860

All ancient cosmologies which speak of a world-encircling serpent say that its body formed the river or ocean shielding the organized earth from Chaos. The serpent, dragon, or crocodile, in the Egyptian system, thus denotes the celestial watercourse. (Hence, the primeval serpent encircling Atum not only emerges from the cosmic sea; it is itself “the outflow of the Primeval Flood.”)861

Sumero-Babylonian cosmology knows “the river of the girdle of the great god—“a world-encircling ocean which is also called “the river of the snake.”862 According to Hebrew and Arabic thought, states Wensinck, “The whole of the earth is round and the ocean surrounds it like a collar. Other authors compare the circle of the ocean around the earth with a wreath, a ring, or with the halo round the moon. The commonest image of the ocean, however, is that of a serpent.”863 Thus the famous Leviathan

“grips his tail between his teeth and forms a ring around the ocean.”864 The Scandinavian Midgard serpent occupied the same circular sea, biting his tail.865 The Greek Okeanos, the boundary of the world, was the serpent Chronos.866 Even the Aztecs knew “the sea as a circumambient Great Serpent.”867

Nor can one ignore the identical serpent enclosing, or forming, the great god’s throne. Muslim legends recall a brilliant serpent around the throne of Allah: “Then Allah surrounded it by a serpent . . . this serpent wound itself around the throne.” 868 The same serpent, in Hebrew accounts, wound itself around the cosmic throne-wheel of Solomon: “And a silver dragon was on the machinery of the throne.”869 “ . . . And a silver serpent bore the wheel of the throne.”870

One remembers also the serpentine wheeled seats of such Greek figures as Triptolemos and Demeter.871 The seat of the Mayan god Anhel is a serpent,872 much like the snake-seat of the primordial pair recalled by the Miztecs.873 Just as the Egyptian serpent-dragon Set becomes the throne of Osiris, so do the parallel figures of Tiamat and Leviathan become the thrones of Marduk and Yahweh in Babylonian and Hebrew imagery.874

So also is the temple likened to the circular serpent. Sumerian hymns describe the cosmic temple “in heaven like a dragon gleaming.”875 This dragon-like abode answers to the Babylonian sanctuary of Ea, represented by a serpent or fish.876 Belonging to the same class are the Uraei who form the walls of the heavenly dwelling of Osiris,877 the serpentine temples or dracontia of Abury,878 the “Iguana House” of Mayan ritual,879 and the girdling snake of the Greek Achis, which surrounded the temenos or inner shrine of the gods.880 The Muslims declare that at the founding of the Sacred House of the Ka’ba, a serpent with a “glittering appearance” wrapped itself around the wall “so that its tail approached its head.”881

The great father’s dwelling was the encircling serpent or dragon—issuing from the cosmic sea. And it matters not whether the abode be termed a “temple” or a “city,” for the cosmic city was equally tied to the imagery of the circular serpent, as confirmed by Egyptian illustrations of a serpent encircling the district of Hermopolis;882 the Hebrew imagery of Leviathan surrounding the primeval, celestial Jerusalem; and the serpentine enclosure of the Teutonic Asgard, the city of the gods.

Always we encounter the same serpent, glittering in the light and marking out the primordial enclosure. In the case of the Egyptian Eye and crown the identity with the Uraeus serpent is spelled out with uncanny boldness. Egyptian hymns locate the enclosing Uraeus on the “brow’ of the great god, and this circular serpent is at once the band of the single Eye and the circle of the crown:

He has come to you, O NT-Crown; He has come to you, O Fiery Serpent . . . O Great Crown . . . Ikhet the Serpent has adorned you . . . because you are Horus encircled with the protection of his eye.883

O King, the dread of you is the intact Eye of Horus, the White Crown, the serpent-goddess who is in Nekheb.884

To wear the crown is to wear the Fiery Serpent, which, in turn, is to reside within the enclosure or “protection” of the Eye. Though offering no explanation, Clark recognizes the identity of these cosmic images: “The Eye is elevated as the defensive cobra which—on the pattern of the earthly pharaohs—encircled the brows of the High God,” he writes.885

42. The circular serpent encircling Hermopolis

The connection immediately explains why the Sumerian Mus-crown, conceived as a golden band, was “the great

dragon.”886

Though the circular serpent appears in many guises, at root there is only one such creature, for its diverse forms

—as the Cosmos, “earth,” temple, city, throne, crown, and Eye—are simply the different mythical formulations of the circumpolar enclosure.

These unnatural roles of the circular serpent—which mythologists tend to regard as the most irrational and unfathomable aspects of ancient symbolism—actually provide one of the most significant unifying threads.

In Summary: A Coherent Doctrine

Saturn’s primordial home was a simple enclosure, a dwelling universally recorded by the sign . Mythmaking imagination expressed the enclosure in many ways, and it is the very variety of formulations which testifies to the band’s overwhelming impact on the ancient world.

To deal meaningfully with this imagery one must admit the influence of a celestial order vastly different from that familiar to us today. We customarily think of “myth” as the opposite of “reality.” Yet the consistency of the testimony suggests that the mythical view, passed down to us through sacred signs, monuments, and literature, connects us with a very real world confronted by the first mythmakers.

The present heavens explain neither the ancient rites of kingship nor the array of astral symbols which grew up around the king—who was conceived as the human incarnation of the ruling divinity in heaven. Always, the ritual and symbol refer to an age different from our own, an age when Saturn, the central sun, ruled from the celestial pole, encircled by his band of “glory.”

Saturn’s band was the primeval Cosmos, viewed as the planet-god’s own consort, the womb on the cosmic waters. The myths alternately depict the band as a revolving island in the sky, a cord of rope forming the boundary of Saturn’s domain, a shining egg, a shield, and the creator’s collar, belt, or girdle.

This was the “earth” which (in the universal creation legend) the great god raised from the celestial sea. In mythical history it became the ancestral land of peace and plenty—Adam’s paradise. Saturn’s kingdom possessed the form of a great wheel; it was the creator’s revolving throne, the celestial city, the lost navel or Middle Place, where (cosmic, mythical) history took its start. Around the border of the heavenly “land” flowed a circular river or ocean.

The same band was Saturn’s revolving temple, which he wore as a crown and in which he dwelt as the pupil of the all-seeing Eye. As the cosmic vase, the band housed Saturn’s waters of life.

And finally, Saturn’s band appears in the guise of a shining serpent wrapped around the central sun and denoted by the Egyptian sign .

Divorced from the archetypal enclosure the various symbols (temples, crowns, thrones, wheels, etc.) appear as isolated forms of uncertain origin. We simply take them as “facts.” Why, then, were these forms systematically related in language, art, ritual, and myth? It is not a question of later generations recklessly joining unrelated images. The further back we go the greater the unity. The best evidence of the harmonious vision comes from the oldest sources of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Here we find the central sun wearing the cosmic city and temple as a crown; taking as his throne the eye of heaven, the holy land, or the vase of upper waters; shining in the centre of an egg called the “earth”; and encircled by a river which forms the wall of the temple but also the circle of the gods. In each case we find that the symbol refers directly to the womb of the mother goddess enclosing the great father Saturn.

In reviewing this imagery of the enclosure one confronts many dominant motifs of ancient religion. Whatever the mythical formulation of the band, the hymns celebrate its presence at the polar centre. Yet who can locate a source of the imagery in today’s tranquil heavens? Where is this revolving river of “splendour and terror”? Where is the city of “the White Wall,” the “clear and radiant” holy land, the temple “like a dragon gleaming,” the “throne of light,” the “golden” egg, or the “fiery” serpent?